Global trade is slowing as the Ukraine conflict and its consequences have replaced the pandemic as the leading drag on growth. Trade will grow at a slower average rate than GDP in the coming nine years, reversing the pattern of trade-led global growth that has prevailed in recent decades. Familiar trade patterns will shift, not only as a result of the war in Ukraine, but also owing to Western nations’ decreasing reliance on China trade and to the rise of economic blocs such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as companies continue to diversify their supply chain risks.

World trade will continue to grow, but at a rate of just 2.3% per year through 2031, according to a Boston Consulting Group analysis—less than the 2.5% annual increase forecast for global economic growth. (See “BCG Trade Methodology.”)

BCG Trade Model Methodology

The model uses ten years of historical data and ten-year forecasts that are based on the correlations among data such as GDP growth, key commodity prices, and certain macroeconomic indicators. Inputs for the raw data forecasts come from reputable sources such as governments, international financial institutions, and economic analysis firms. The baseline output of the model covers more than 180 exporting countries and more than 5,000 product categories in 22 sectors. It includes manufactured products and raw materials; services are excluded. Trade values are expressed in constant 2021 US dollars.

Once the baseline is established, the BCG Global Advantage and BCG X teams incorporate adjustments that factor in geopolitical events or trends that influence global trade but are not captured by the baseline model. These factors may include influences such as new trade agreements, trade wars, military conflicts and related sanctions, and climate-related trade policies. The team establishes adjustment scores and applies these, on a percentage basis, to a five-year baseline trade forecast and uses this to create the ten-year trade projection.

Assumptions

The 2022 model includes a number of notable geopolitical assumptions, including the following:

- The ongoing sanctions regime against Russia and Belarus remain in place through 2031.

- The EU and US stop trading with Russia for the forecast period, except for critical supplies.

- The EU successfully ends its dependence on Russian energy by 2027.

- Russia trade is diverted mainly to China, India, and other emerging markets.

- No significant new trade agreements are established in the 2023–2031 period.

- The EU implements its carbon border tax (CBAM) in 2026, as planned.

- ASEAN trade—in particular, ASEAN-US and ASEAN-EU exports—rise at a faster rate than in the past due to a reduction in the growth of China exports to the US and the EU.

Regional Definitions

The 2022 model uses the following definitions for regional organizations and areas:

- The European Union includes all 27 current member countries.

- The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates.

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- Mercosur includes its current active members—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

- Africa comprises all countries of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCTA).

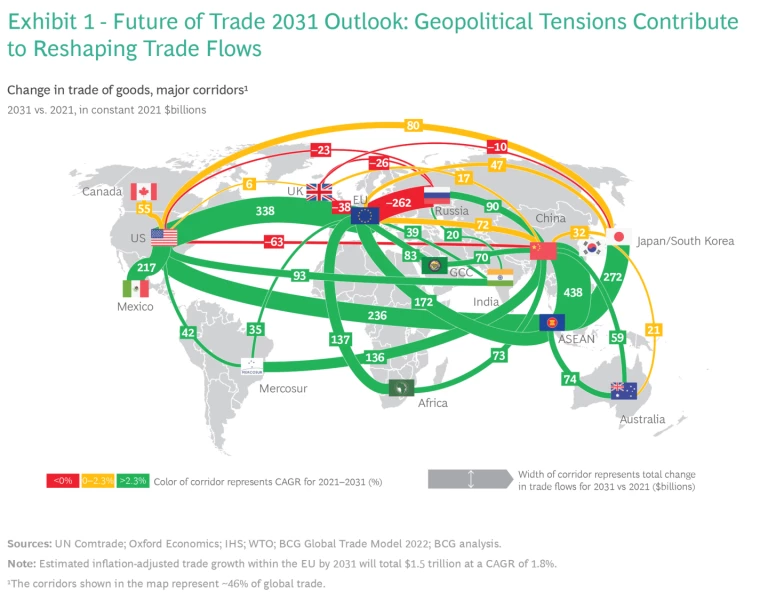

As economies adjust to changing geopolitical and economic dynamics, including inflation and potential recession in the near term, the resulting shakeout will produce new global winners and losers. (See Exhibit 1.)

The impacts will be especially strong in three areas:

- Russia-West Fallout. Trade between the EU and Russia will decline sharply, shrinking by $262 billion during the period from 2023 to 2031, as Western sanctions on Russia take effect and Western Europe weans itself from its dependence on Russian oil and gas. Russian trade will shift from Europe to other regions, particularly China and India. The most disruptive impacts will occur in the energy sector, but the changes will affect other commodities as well.

- China Trade Dynamics. Trade between the US and China will decrease by $63 billion through 2031. EU-China volumes will grow, but at a slower rate than the global average, as companies focus on increasing their resilience. These trends will drive world trade growth with ASEAN countries, India, and Mexico, as near-shoring and friend-shoring gain pace.

- ASEAN Trade Growth. Southeast Asia will be the principal beneficiary of the redrawn trade map. The region will see significantly greater trade with China, the US, Japan, and the EU, driven by companies’ desire to diversify global supply chains in the face of growing geopolitical tensions and the rising costs of manufacturing in China. ASEAN trade with China will grow by $438 billion, the largest interregional increase on our 2031 map. Companies will be attracted to Southeast Asia by the region’s lower costs and the growing breadth and depth of its manufacturing capabilities. (See Exhibit 2.)

A Less Friendly Trade Environment

Overall, the anticipated changes will continue to dilute the economic globalization and trade opening that characterized the first three decades of the post–Cold War period (the 1990s to 2010s). By contrast, the rising trade tensions and economic nationalism that have appeared in recent years accelerated during the pandemic and are projected to persist in coloring world trade relationships over the coming decade. In this environment, corporations are diversifying their trading relationships to reduce global investment and supply chain risks.

The biggest shock to world trade is attributable to the military conflict in Ukraine, which will have significant economic impacts as both the EU and Russia look elsewhere to fill trade gaps created by the rupture. Over the nine years, from 2023 to 2031, the EU will increase its trade with the US by $338 billion, driven in large part by increased US energy exports to Europe, and will also see a huge expansion in combined trade with ASEAN countries, Africa, the Middle East, and India. Meanwhile, Russia’s trade with China and India will grow by $110 billion, including $90 billion with China alone.

The US government’s efforts to promote domestic manufacturing and encourage companies to diversify supply chains started during the Trump Administration and are continuing under the Biden Administration, in the form of such measures as the US Inflation Reduction Act, the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, and the US CHIPS Act, all of which aim in part to lessen the country’s trade dependence on China.

The EU has likewise adopted an increasingly China-wary stance as trade and investment dynamics between the EU and China have become more challenging. An escalating wave of tit-for-tat punitive exchanges started in early 2021 with EU travel bans of Chinese trade officials in a dispute over the EU’s allegations of forced labor in Xinjiang, followed by the EU’s suspension of ratification of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (signed in December 2020). This was followed by the EU’s challenge in the World Trade Organization over China’s trade embargo of Lithuania after that country opened a trade promotion office in Taipei. As a result, trade growth between the EU and China is cooling, with two-way commerce forecast to grow by just $72 billion through 2031, a modest increase in comparison with growth in previous years and lower than the 2.3% average global growth forecast.

One effect of slowing Western trade with both Russia and China will be a corresponding rise in commerce between northern and southern regions as countries find new trading partners in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. The clear winners here are the ASEAN countries, which are projected to see new commerce—especially with China, Japan, the US, and the EU— boost trade by more than $1 trillion through 2031.

More broadly, the evolving trade map shows relationships coalescing around a new East versus West dynamic—a US- and EU-led community and a China-Russia counterpart—along with the potential emergence of a third bloc of ostensibly neutral nations. In a modern echo of the Nonaligned Movement of Cold War days, this group of mostly developing-world countries—including Indonesia and other ASEAN countries, India, Brazil, and African nations such as South Africa—will find opportunities to expand trade by stepping into trade vacuums created by relationship breakups elsewhere.

Certain industries will feel the global disruptions more keenly than others, with energy being the most heavily impacted sector due to the West’s phasing out of Russian oil and gas and the scramble to replace Russia as an energy source. Pressure on organizations to improve sustainability and increase use of alternative energy sources will also continue to affect corporate energy strategies and operations worldwide. Meanwhile, industries with intricate global supply chains—such as semiconductors, automobiles, and consumer electronics—will also face difficult transformations as companies take steps to improve resilience and reduce their reliance on China manufacturing.

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

Preparing for Risks in a Challenging Landscape

The comparatively secure trade environment that enabled companies to develop extensive world supply networks over the past 30 years has given way to a more uncertain one that will demand a new balance between the traditional objectives of efficiency and lower costs on the one hand and a heightened awareness of global risks and the steps needed to mitigate them on the other.

Recent global trade patterns provide clear evidence that many organizations are already prioritizing supply chain resilience and global diversification. In the short term, companies should take several actions to adapt to the evolving global economic situation:

- Evaluate opportunities in the value chain to improve responsiveness.

- Prioritize steps to increase resilience such as building up buffer inventories of essential commodities and prequalifying alternative suppliers.

- Plan contingencies for at-risk supply inputs identified in value chains. For example, companies can fund R&D to identify alternatives for rare minerals, or they can develop supplier relationships in different global regions.

In the long term, companies should pursue a number of additional objectives:

- Accelerate efforts to incorporate geopolitical scenario planning into capital allocation and supply chain management processes. Scenario plans should aim to improve long-term supply chain resilience in support of the overall growth strategy.

- Emphasize environmental, social, and governance (ESG) objectives, which have implications for global supply chains.

- Assess available talent, with the goal of having people in leadership roles who can identify and manage global risks as early as possible.

- Use modern analytical tools, such as supply chain control tower and digital twins, to improve the early visibility of emerging shocks or disruptions and to visualize scenarios and contingencies. (See Exhibit 3.)

Global trade has been challenged in recent years by protectionism, pandemic, and war. The impacts of these forces will influence trade flows around the world for the foreseeable future. Companies that rely on global supply chains should recognize that the challenges confronting global trade are here to stay, and should continue diversify their networks and build resilience.