There are more than 42 million refugees, asylum seekers, and other people in need of international protection worldwide.

In 2022, as the Ukrainian refugee crisis unfolded, BCG launched a research initiative to better understand the challenges these refugees face. Our objective was twofold. The first is to provide a nuanced view of the different Ukrainian refugee groups and the specific needs each group faces along their journey as refugees. The second is to show how organizations can address the refugees’ long-term challenges, particularly those relating to employment and economic inclusion. As part of our research, we conducted in-person interviews with and surveyed Ukrainian refugees in neighboring host countries. (See “Methodology.”)

Methodology

Our research underlines that refugees need assistance at every step if they are to succeed in securing employment. This starts from support with obtaining eligibility to work in a host country and the job search to aid with the applications process and onboarding once employment is secured. No single organization can tackle this complex task. Networks of stakeholders—governments, business, and civil society—are needed to form support ecosystems for refugee job seekers. Here, we provide practical advice on how stakeholders can work together to realize these employment ecosystems not only for Ukrainian refugees but for refugees worldwide.

Networks of stakeholders—governments, business, and civil society—are needed to form support ecosystems for refugee job seekers.

Understanding the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis

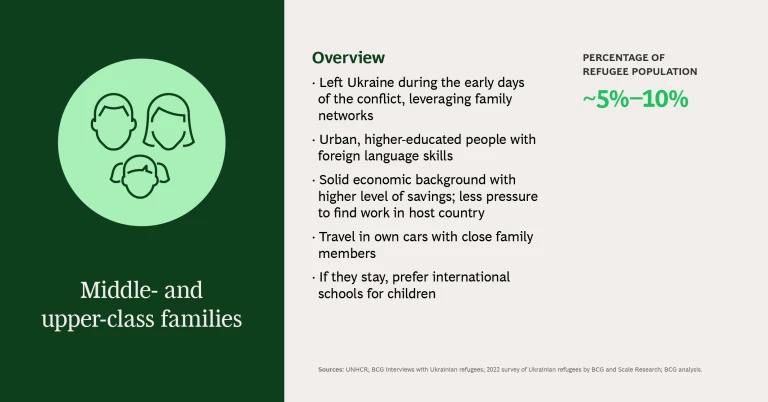

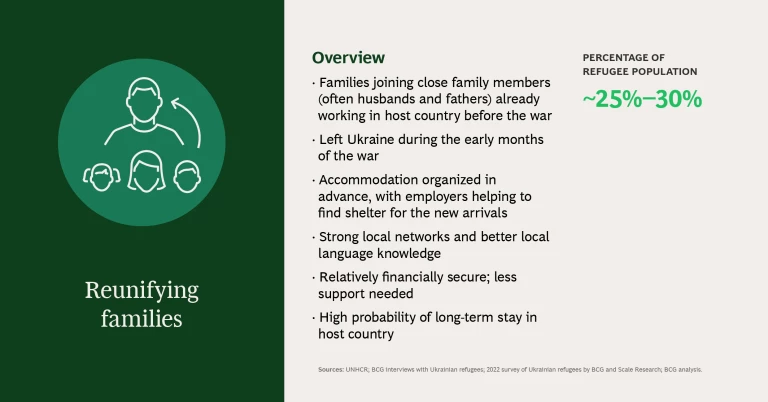

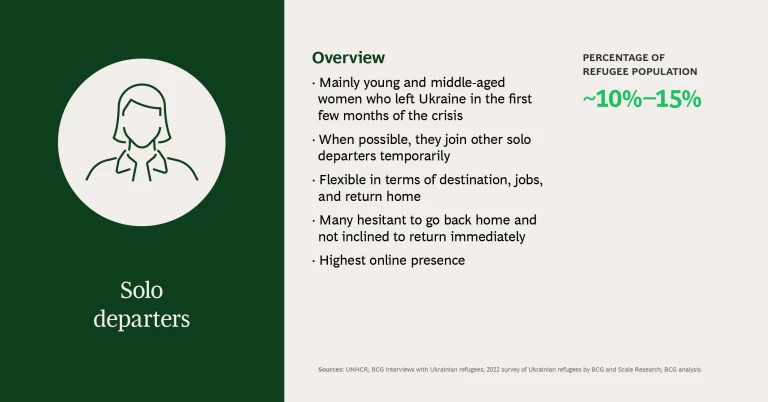

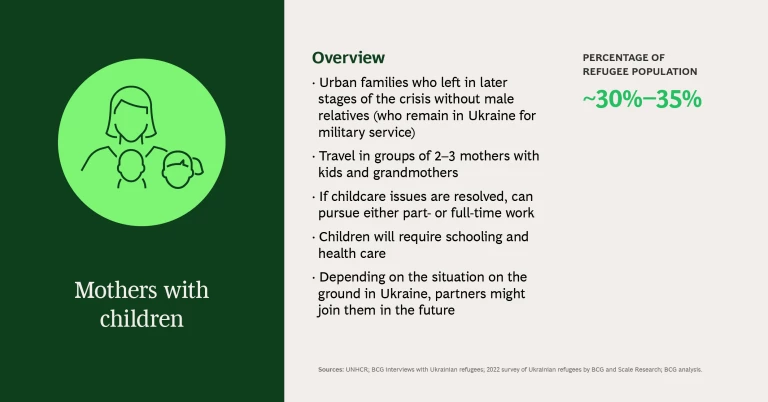

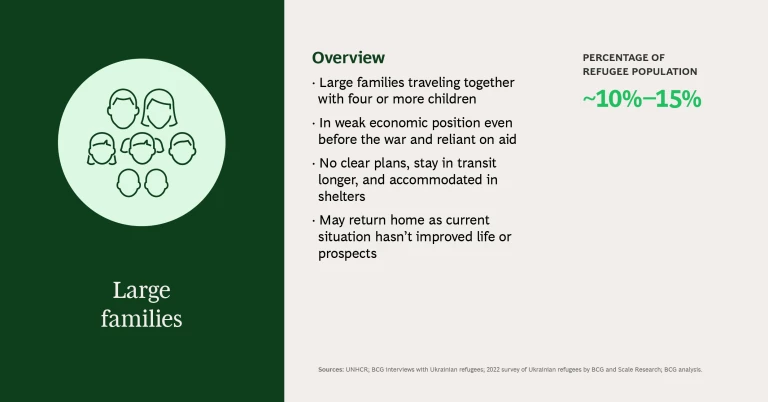

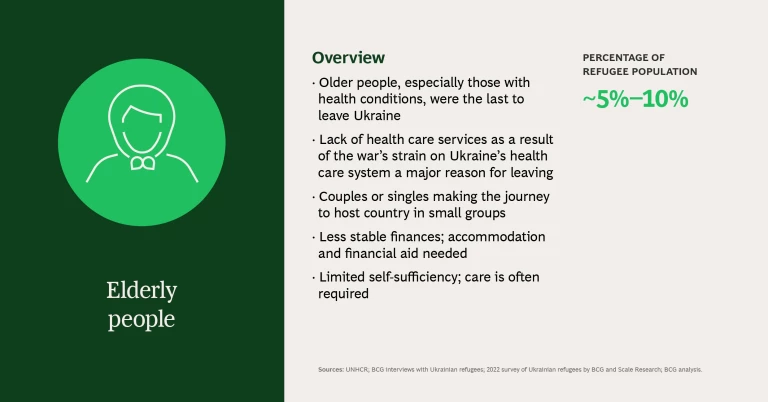

Ukrainian refugees can be largely segmented into six groups, according to BCG research, each with distinct characteristics and needs. They are upper- and middle-class families; reunifying families (often wives and children joining spouses and fathers working in host country before the war); solo departers (mainly young and middle-aged women); mothers with children; large families; and elderly people. (See the slideshow.)

The Ukrainian refugee influx is different in many ways from the other refugee crises that Europe has witnessed in recent times.

First, as a group, Ukrainian refugees benefit from significant legal protections. Since March 2022, as per the European Union’s Temporary Protection Directive, externally displaced Ukrainians are eligible to work and access social welfare services in the EU member states that grant them residence permits—without having to obtain formal refugee status. Non-EU countries like Moldova also launched their own temporary protection schemes for Ukrainian refugees.

Second, the Ukrainian refugee exodus is overwhelmingly female. Because of conscription, Ukrainian men between the ages of 18 and 60 years aren’t allowed to travel abroad. Only some men—such as fathers with three or more children, persons with disabilities, and others qualifying for exemptions—have been able to legally cross the country’s borders. As a result, approximately three-quarters of externally displaced Ukrainians are women, many traveling with young children and elderly relatives.

Third, the vast majority of refugees intend to return home to reunite with their partners sooner or later. Most surveys, including the one we conducted, show that 70% to 80% of Ukrainian refugees hope to return home when the war is over. They tend to regard their flight as temporary and do not intend to remain in their host countries permanently.

Fourth, and partly as a result, most would prefer to stay and find work in European countries neighboring Ukraine, from where they can easily go back home. In fact, some refugees returned to Ukraine during the fall of 2022, as the fighting around their hometowns abated, and their children’s school years started.

Fifth, for a large number of Ukrainian refugees, learning the local language—an important step in finding suitable employment—will be less difficult than for other arrivals. Ukrainian and Russian, the main native languages of Ukrainian refugees, share similarities with Polish, Slovak, and Czech. Collectively, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic are hosting more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on social impact

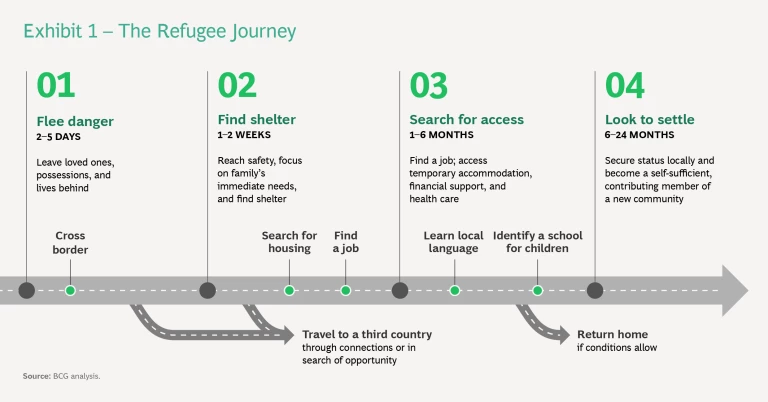

The Four Stages of the Refugee Journey

Like externally displaced people everywhere, the Ukrainian refugees have begun a four-stage journey. They’ve been forced, in order of urgency, to flee danger; seek shelter; gain access to a new country; and settle. The first two stages, when the refugees’ focus is on immediate needs, usually last a few weeks. After entering a safe country, more than 50% of the Ukrainian refugees moved to other countries or regions in the next few weeks. These decisions usually depend on the location of members of the extended family, the proximity to the Ukrainian border; cultural and linguistic affinity; and the availability of jobs. (See Exhibit 1.)

Today, most Ukrainian refugees are in the third stage of their journeys: trying to gain access to and benefit from host countries’ social support, health care, and other systems as they drew on their meagre financial reserves. With many refugees hoping to put down economic roots in their host countries and move to the next stage of their journey access to both short- and long-term employment is increasingly becoming critical.

Refugee Job Searchers Face Many Challenges

Nearly two-thirds of Ukrainian refugees rely or need financial support. Different forms of financial aid are available, but they are often inadequate to enable refugees to become self-sufficient. Finding employment is thus critical.

Among the group of refugees we surveyed in 2022, assistance with employment topped the list of areas where assistance was needed. This group was relatively young, highly educated, and extremely motivated to work. Some 88% were between the ages of 18 and 57, and 73% of the respondents were college educated. Their work histories spun a diversity of sectors—from business and health care to agriculture and transportation. At the time, 51% of them were looking for a job; 26% already secured a job in their host country or were able to work remotely in their old job; 16% did not have the right to work; 5% did not know; and only 2% did not need to work.

Assistance with employment topped the list of areas where assistance was needed among Ukrainian refugees surveyed.

However, Ukrainian refugees, as our survey and interviews indicate, face significant challenges to securing employment.

Eligibility. Without registering with the governments of host nations, these refugees cannot take up employment legally. The paucity of legal information in languages they understand as well as the bureaucratic nature of migration processes hinder their ability to obtain work permits. Even if they obtain formal refugee status, externally displaced Ukrainians will be able to work only in the country in which they’ve registered.

Language. Many Ukrainian refugees have bachelor’s and other higher degrees. They have held office jobs or worked in service industries. They’re trying to look for similar jobs in their host countries, but without knowing the host country language or English, their employment opportunities are limited. Business processes are rarely executed in nonlocal languages and deploying interpreters in the workplace is costly and time consuming for employers. At least initially, many companies will only offer Ukrainian refugees jobs consisting of repetitive tasks and minimal communication requirements.

Accommodation. In many countries, governments locate transit and refugee camps in areas where job opportunities are extremely limited. Without inexpensive accommodation close to where the hiring companies are, it will be extremely difficult for Ukrainian refugees to find jobs.

Childcare. Because many Ukrainian refugees are mothers with young and school-age children, they can only go to work if some form of child daycare is available. Even with the provision of childcare, family responsibilities will make holding full-time jobs impossible for many women.

Uncertainty. Most Ukrainian refugees are perceived to be looking for short-term or temporary employment because most hope to return home eventually. That doesn’t appeal to would-be employers that must invest time and money to ensure that refugees are work ready.

Health. Many Ukrainian refugees suffered from the psychological and physical trauma of war as well as other health conditions. Their loved ones face difficult situations back home or are on the war’s frontlines, which poses a major psychological strain.

Expectations. Based on past experience and stereotypes, some companies have been offering Ukrainian refugees jobs that require manual labor and other physical skills. But many female Ukrainians aren’t willing or able to perform such tasks. This has resulted in a mismatch between the demand for and the supply of jobs.

Exploitation. Some employers and middle persons try to take advantage of this vulnerable population for financial benefit. They offer jobs to Ukrainian refugees in the shadow economy and pay below-market wages or even not pay at all, which pushes the most vulnerable refugees into even worse situations.

All of these are significant hurdles, but stakeholders can come together to empower Ukrainian refugees to find suitable and legal employment.

Creating Refugee Employment Ecosystems Is Critical

While finding a job is a difficult task for externally displaced Ukrainians, companies also face challenges in hiring them. Although Ukrainian refugees appear to be a talent pool that business can readily tap, this isn’t the case. It’s tough to identify and track Ukrainian refugees; many keep moving until they feel safe. It’s also difficult for employers to communicate with them by using their usual communication methods, such as ads in newspapers or social media accounts in the local languages.

Some recruiters, job search websites, NGOs, governmental organizations, and Facebook groups across Europe have supported Ukrainian refugees’ employment searches. Projects such as Imagine Ukraine and JOBLINGE’s work4U initiative in Germany are catalyzing employment through mentoring and job matching and have made placements. While these are among the better solutions to address labor market issues facing Ukrainian refugees, more resources and coordination are needed to scale such initiatives build effective solutions beyond their somewhat limited reach and best serve what is a very heterogenous pool of job seekers.

A change in mindsets, approaches, and tools is essential to tackle this situation. It’s nearly impossible for one business or a single NGO to tackle the problems facing refugee job seekers; no one has all the capabilities or funding needed to do so. The best solution is to create support ecosystems, using digital platforms, that enable the connection and collaboration among multiple stakeholders.

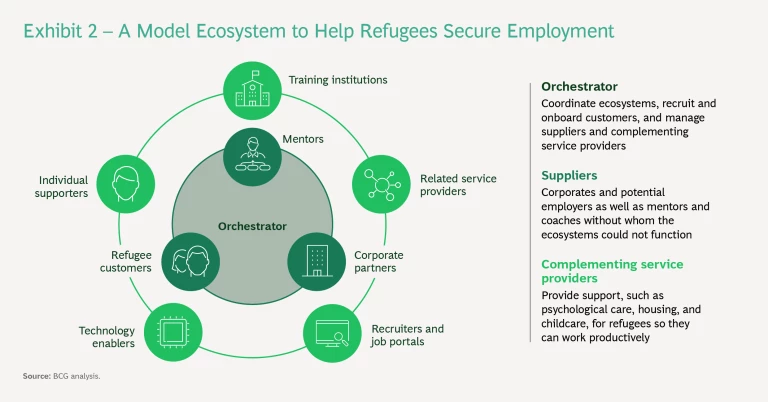

Creating employment ecosystems is critical when a high degree of flexibility and operational agility is needed to respond to a quickly changing situation. Each ecosystem’s main stakeholders can be best thought of as customers, orchestrators, complementors, and suppliers. (See Exhibit 2.) In this case, the refugees needing employment are the customers; they will benefit from an ecosystem’s offerings and will contribute to it in different ways such as providing data and feedback.

The organization running an ecosystem will act as an orchestrator, responsible for setting up the ecosystem and defining the rules of engagement. Orchestrators are critical due to the central role they play in controlling the important resources needed to solve business problems. In this case, the resources consist of databases of registered refugees, job opportunities, and organizations that can support the matching and placement process.

Both government organizations and NGOs can play this role, individually and jointly. For instance, Romania’s Dopomoha.ro (which translates to “help” in Romanian) is a central information platform for Ukrainians entering Romania. The platform is available in Romanian, Ukrainian, English, and Russian and is accessible by browser on any device. The project was developed by the Code for Romania, Romania’s Department for Emergency Situations, the UNHCR, the International Organization for Migration, and the Romanian National Council for Refugees, and is financially supported by ING Romania.

Companies offering suitable job opportunities and the mentors and coaches supporting the placement process will be key suppliers. (See “How Employers Can Support Refugees.”) Others that enhance the support ecosystem’s value are the complementing service providers, such as educational and training companies, which must support the refugees to boost their prospects.

How Employers Can Support Refugees

Before Hiring

- Companies must prepare systematically to employ refugees. The Immigrant Employment Council of British Columbia organizes roundtables with potential employers that help identify potential barriers to hiring refugees—from misconceptions about the refugee workforce to language barriers—and take steps to address them.

- Business leaders must create diverse, inclusive, and refugee-friendly environments. Amplio Recruiting, a US-based staffing agency specializing in connecting employers with a refugee workforce, recommends going beyond asking how a company can hire refugees and determining what needs to change in the workplace if immigrant employees are to thrive. This includes preplacement trainings for the management and teams that the incoming refugee employees will be joining.

- Companies must ensure that refugee applicants get access to information and undergo job interviews in their own languages. Companies should prepare bilingual job descriptions and contracts, using technological solutions such as mobile applications and interpreter call centers. In the United States, the food company Chobani conducts job interviews in multiple languages and provides employment documentation and contracts in multiple languages.

- Companies should focus on the candidate’s relevant experience, academic background, and fit with the company. Using scenario-based questions allows executives to test the refugee’s performance.

- Onboarding support and early training is crucial to prepare refugees for a successful start. In addition to providing assistance with administration, transportation, and childcare, companies must create supporting materials for refugees like maps, directions, health and safety instructions, commonly used phrases, and daily task descriptions.

- Companies must deploy seasoned employees to lead the teams on which refugees work so the former can mentor and counsel them. Both the US-based nonprofit Jobs for the Future and the Tent Partnership for Refugees, which brings together more than 300 major multinational companies committed to hiring refugees, recommend pairing refugees with partners to assist them with any questions and problems. Organizations should assign a buddy to every new refugee hire, who will help them integrate into the company and society.

- HR managers must stay abreast of newly hired refugees’ performance through formal and informal channels and handle any conflicts with tolerance. For instance, Talent Beyond Boundaries, a nonprofit connecting refugees with jobs internationally, recommends regular check-ins with new hires and their managers throughout a refugee hire’s first year on the job.

Career Building

- Supporting refugees’ personal development and paying special attention to factors that influence their retention are important. In Australia, IKEA has introduced a Skills for Employment program, which provides refugee and asylum seekers with paid employment and skills training.

- Companies should provide language-training opportunities, prepare language guides, and use technology to tackle language barriers. In Sweden, business has introduced a Fast Track initiative to speed up integration, which enrolls refugees in Swedish language courses the moment they arrive.

Another vital component, especially during the launch phase, is the (financial) catalyst, whose role is to enable the launch and operations of an ecosystem for society’s benefit. Most ecosystems of this type don’t generate direct financial value but need resources to operate. Humanitarian organizations, such as the UNHCR, usually get the participants on board, and ensure that the operation is funded.

Providing employment for externally displaced Ukrainians can be a win-win for refugees and their host countries.

Refugee employment ecosystems tackle several problems. They facilitate collaboration between volunteers, civil organizations, businesses, and governmental entities, which will deliver optimal results. The ecosystems will also be able to aggregate potential employers and other service providers, as well as refugees, to facilitate more matches. As trusted third parties, they can provide the hardest-to-reach refugee segments with the resources they need. Above all, the ecosystems can ensure that companies focus on the most vulnerable refugee segments.

Providing employment for externally displaced Ukrainians can be a win-win for refugees and their host countries—and point to effective solutions that will help refugee labor market integration in the years to come. Today, many European countries are grappling with aging workforces and shrinking populations. Ukrainian refugees can help fill talent shortages in sectors such as information technology, health care, hospitality, manufacturing, construction, and transportation. Creating national employment ecosystems that match the demand and supply for labor, make companies more refugee friendly, and prepare refugees for in-demand jobs is therefore critical. Governments, business, and civil society have to come together to make that happen. Countries that embrace refugees stand to gain an economic advantage, drive innovation, and enrich their societies as a whole.