US hospitals are facing the most challenging economic environment in recent history. Absent significant intervention, we project that the annual financial shortfall of US health systems will total more than $200 billion by 2027. Inflationary pressures and labor shortages are only the tip of the iceberg. The more substantial issues are structural challenges that fundamentally threaten health system economics and their ability to provide care. Even well-capitalized health systems will find it difficult to deliver on their mission.

Addressing the challenges requires collective action. Leaders at many health systems are already making tough choices: curtailing services, cutting costs, and asking their clinicians and staff to do more with less. But they must look beyond these incremental cost-saving measures to transformative changes that will put their economics on a firmer footing and ensure continuous performance improvement going forward. Government (Medicare and Medicaid) and private payers also have a part to play by working with providers on more sustainable reimbursement rates and new value-based payment models that promote more cost-effective approaches to patient care.

If the systemic issues are not resolved, the situation facing health systems will worsen, with enormous consequences for patient care and care equity. Below we outline the challenges ahead and the steps that health care leaders need to take to ensure a sustainable, resilient US health system for years to come.

Systemic Issues Bite Hard

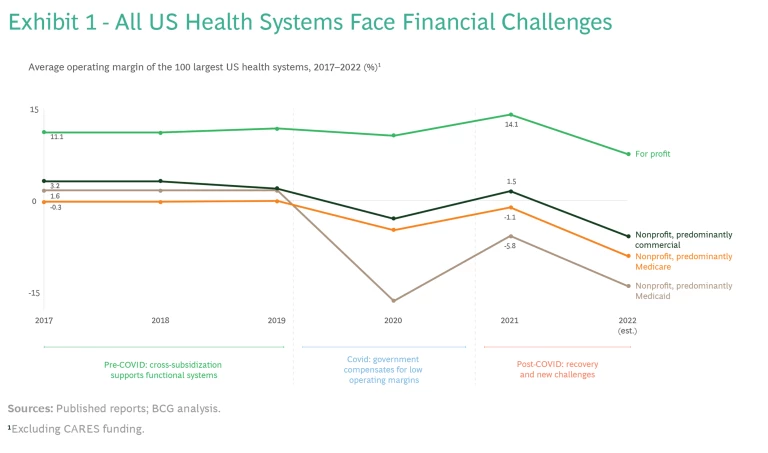

US health systems just completed their worst financial year in decades (See Exhibit 1.) Kaufman Hall found that more than half of US systems incurred negative operating margins in 2022. Last year also saw 19 hospital closures or bankruptcies, according to Becker’s Hospital CFO Report. This year promises to be worse.

The economic challenges are already being felt by caregivers, such as doctors and nurses. Becker’s Hospital Review reports 18 strikes by health care workers in 2022. A recent nurses’ strike in New York City made national headlines. According to Definitive Healthcare, 117,000 physicians left the sector in 2021. (See “Physicians Feel the Pain.”)

Physicians Feel the Pain

Worsening economics will make it more difficult for health systems to retain talent in specialties where there are alternative employers, such as private equity-owned practices, or alternative models, such as “concierge” care, which caters to more wealthy patients. The 2% cut in Medicare payments to physicians in 2023, following two decades of flat rates, may push more physicians to opt out of seeing Medicare patients, which will exacerbate access challenges for economically disadvantaged patients and broaden care inequity.

The ramifications go further. Losses on the scale we project undermine providers’ ability to sustain their missions. Health systems provide essential services to the community, and often there are no viable alternatives. Health systems also are frequently among a region’s biggest economic engines and largest employers. Sustained losses could have impacts that extend beyond the health care sector .

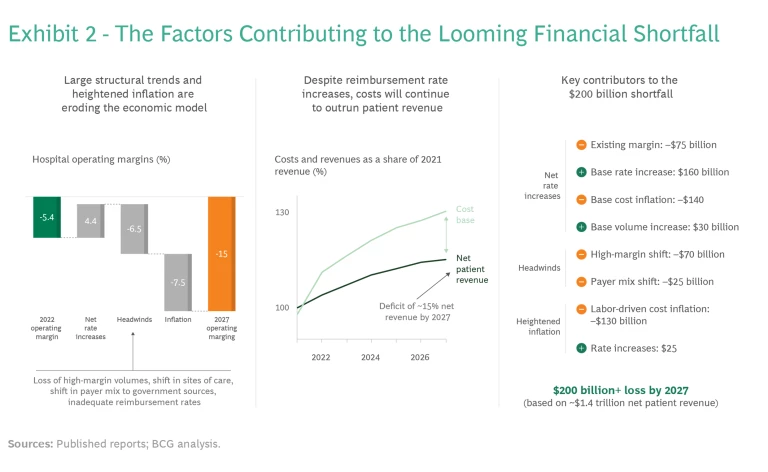

Four entrenched trends are shaping the financial outlook for providers and without intervention will lead to a 10 percentage-point drop in operating margins by 2027. (See Exhibit 2.) These are the migration of patients away from acute-care settings, demographically driven shifts in the payer mix, uneven changes in patient volumes, and inadequate reimbursement rates.

Patient and Service Migration

In a trend accelerated by the pandemic, we expect a continuing exodus from acute settings of high-margin services, such as elective orthopedic, neuro and spine, oncology, and cardiac procedures, which can account for a significant portion of net patient revenues in a typical health system. Patients clearly prefer receiving care in more convenient, consumer-friendly outpatient locations to visiting a hospital campus. Physicians often feel similarly, and payers continue to encourage this shift given the lower costs associated with treatment outside a hospital.

In some cases, these services will move to hospital-managed ambulatory settings, but more often, they will leave the system altogether (to physician-owned, venture capital-backed, or private equity-owned service companies, for example). While this migration offers the potential of similar patient outcomes at lower cost, it also erodes the financial stability of many health systems. Our projections indicate that a typical health system can expect to lose 20% to 30% of current revenue from these high-margin services by 2027, resulting in a 4 to 5 percentage-point drop in operating margins.

Payer Mix

We are in the midst of a steady evolution in the typical health system’s mix of payers from commercial insurance to government-funded sources, including Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and subsidized Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace plans. As the population ages, some 17 million baby boomers will have moved to Medicare between 2020 and 2030; about 10,000 patients become Medicare-eligible every day. Medicaid and CHIP enrollments jumped by 20 million people between 2020 and 2022, when they totaled roughly 91 million. The increase was driven by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and by ACA Medicaid expansion in several states.

While these numbers can be expected to fall with the end of continuous enrollment under the COVID-19 public-health emergency, secular trends will continue to push enrollment upwards as the last states implement Medicaid expansion and low-income individuals age into dual coverage. ACA marketplace enrollment has also grown steadily, as many smaller employers move their employees onto the exchanges through Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangements and other vehicles. ACA marketplace signups increased 13% for 2023.

The hard facts for hospitals are that Medicare reimburses at roughly half the rate of commercial payers, ACA marketplace plans at about 60%, and Medicaid at about 40%. Every lost commercially insured patient puts a significant dent in top-line economics and hits the bottom line even harder. For a typical health system, this demographic shift will lead to a 1 to 2 percentage-point decrease in operating margin by 2027.

Patient Volumes

At the national level, patient volumes have mostly recovered to prepandemic levels, but the recovery has not been evenly distributed. Large, well-capitalized health systems continue to pick up a greater share of patient volumes, while smaller regional hospitals are at risk of permanent volume loss. Volumes have also shifted in ways that are financially detrimental for many systems, which are seeing fewer profitable procedures (such as surgical interventions) and larger numbers of less profitable patients with more acute conditions and longer lengths of stay.

Every lost commercially insured patient puts a significant dent in top-line economics and hits the bottom line even harder.

Non-COVID inpatient volumes are expected to remain flat or show only modest increases (not enough to affect operating margins) over the next five years. While outpatient volumes will grow by about 4.5% during that period, health systems that have not established ambulatory alternatives to the hospital will cede much of that volume to other players.

Reimbursement Rates

Even after the rate hikes of 2021 and 2022, hospitals need further substantial reimbursement increases from insurers to offset the double-digit cost jumps and structural economic challenges faced by health systems.

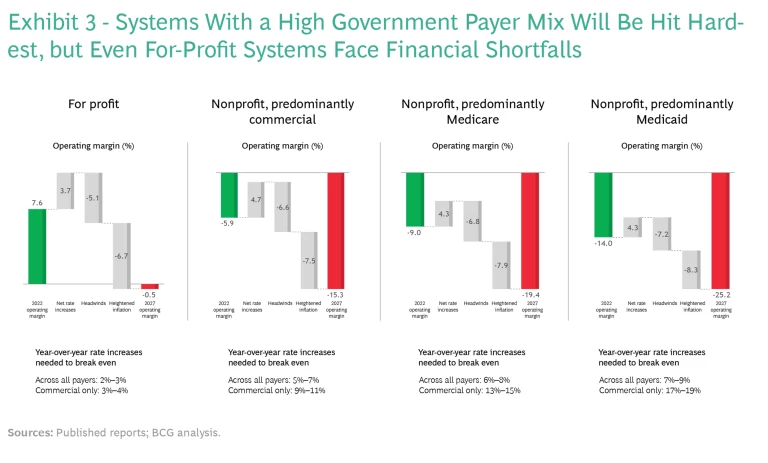

To break even in 2027, the typical health system will need a rate increase of 5% to 8% per year over the next five years across all payer types. This is twice the annual reimbursement growth rate of the past decade. If government payers don’t step up, health systems will require a 10% to 16% year-over-year rate increase from commercial payers.

The magnitude of such increases would require commercial payers to raise premiums significantly for individuals and employers, exacerbating affordability pressures and potentially forcing some employers to reduce benefits, shift more cost onto their employees, or drop coverage altogether. Paradoxically, the latter would result in more government-funded volume for providers (in the form of expanded Medicaid and ACA marketplace enrollees), fueling the cycle for even steeper commercial rate increases in the ensuing years.

Provider Vulnerability Rises

No health system is immune from these demographic, social, and financial realities. Hardest hit will be rural hospitals and those in poorer urban areas. (See Exhibit 3.) Systems with a higher-than-average government payer mix, and those with significant cross-subsidization between high-margin and lower-margin service lines, are also at risk. But even for-profit systems that have greater freedom to choose which markets to serve and which services to offer will see margins erode, and they could face financial shortfalls as well. The inevitable outcome will be less access to care among the neediest populations.

Time for Action

Health systems cannot address these challenges alone, but they still need to take action on the factors they can control. Here are three imperative steps for individual systems:

- Assess the magnitude of the financial challenges.

- Look beyond traditional cost levers to systemic issues.

- Recommit to the core mission of the health system and leverage external partners to do the rest.

These steps require a programmatic approach driven from the top. Transformational change starts with a C-suite agenda that encompasses a comprehensive set of revenue and cost levers, aligns enterprise-wide incentives in an ambitious program, and deploys flexible resourcing to ensure that program goals are achieved. Success also requires a continuous-improvement mindset and governance mechanisms that encourage ongoing innovation and optimization, in the same way that the manufacturing sector ekes out incremental improvements in efficiency or quality every year.

Assess the Magnitude of the Challenges

Multiyear planning is essential to understanding the magnitude of the financial challenges a system faces and setting the ambition for corrective action. Since every system is different, a rapid economic health check can help.

Subscribe to our Health Care Industry E-Alert.

The first step is an objective assessment of the system’s current economic state and the likely trajectory of future cost, service, and reimbursement trends. This analysis should include sizing the effect of high-margin services leaving the hospital and the extent to which some can be recaptured in hospital outpatient and system-operated ambulatory surgical settings. Hospitals also need to evaluate their long-term exposure to an evolving payer mix and to more rapid shifts from an economic recession and develop an understanding of the degree of change required to sustain growth.

Address Systemic Issues

While some cost pressures are temporary, others are deeply embedded. Health systems need to go beyond traditional cost levers (such as reducing administrative expenses and optimizing third-party spending) to the harder work of bringing their core operations in line with their ambitions, strategies, and realistic expectations for the future. This will involve redesigning core processes, eliminating low-value activities, and automating labor-intensive ones. Promoting top-of-license work (with everyone spending their time on tasks that require their peak level of skill) is essential to ensuring long-term system efficiency and to paying for the multiyear wage hikes that are being secured by nurses and other clinical staff.

Health systems need to go beyond traditional cost levers to the harder work of bringing their core operations in line with their ambitions, strategies, and realistic expectations for the future.

The goal is not only to incrementally improve the efficiency of work but to fundamentally rethink work: does it have to be done, by whom, and in what capacity? For example, in areas such as scheduling and check-in, self-service solutions remove these tasks from staff and not only reduce costs but also increase patient satisfaction.

Recommit to the Core Mission

Health systems exist to deliver care, pure and simple. Ancillary on-site businesses (cafeterias and laundries, for example) and related but noncore functions (such as finance and IT) can be better and more efficiently handled with support from external partners, which also frees up resources for the hospital.

In the face of flattening revenues and rising costs, hospitals need to formulate a long-term strategy to tap into new sources of value and direct their investments. They need to answer existential questions about what the health system wants to be able to do in the future, what this implies about changes to the core business, what options are available, and what tradeoffs those options entail.

The biggest challenge for most systems will likely be footprint and service optimization, because the decisions involved go to the heart of any provider’s mission. Ensuring that a system has sufficient scale in procedural volumes at each location—and consolidating where it does not—is necessary to providing responsible care. Diversifying the type and flexibility of facilities in the system’s footprint and being creative about how clinicians and patients connect are critical to serving the needs of harder to reach communities. To facilitate clinician-patient engagement, more systems will need to use a mix of “circuit riding” (clinicians moving around the system day to day), air transport services, and virtual services.

An Existential Challenge Requires Collective Action

Health systems can get only so far on their own. Payers—including Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers—and policy makers must be part of the solution. There are still healthy profit pools in the ecosystem: publicly traded health care companies across the value chain reported significant profits over the last two years (the six largest health insurance companies earned profits of $8.5 billion in the third quarter of 2022). Private equity-backed care delivery startups have found ways to make money, often by providing more convenient, consumer-friendly service.

There can and should be more equitable distribution of private dollars to ensure that hospital closures don’t create health care deserts around the country. But the responsibility for financial viability can’t rest only on private companies. Traditional fee-for-service Medicare accounts for more than half of beneficiaries in the US. The public sector must also be part of the solution, by finding ways to provide higher overall reimbursements, for example, and by experimenting with new payment mechanisms, such as reimbursements that support rural health care delivery and transport of patients to centers of excellence for more specialized care.

Policymakers can take a page out of the experience of fast-developing economies elsewhere that have turned adversity to opportunity by leapfrogging the lack of traditional infrastructure with lower-cost, more technology-enabled solutions. In China, for example, the government legalized online-only health care providers in 2015 and has since poured billions into developing an internet health ecosystem to address overcrowded public hospitals (which were an issue even before the pandemic, given the lack of a strong primary-care system).

A sustainable and resilient US health system is essential to the well-being of patients and their communities. As we recover from a multiyear pandemic and move through a period of high economic uncertainty, all players in the health care ecosystem would benefit from working together toward this worthwhile goal.

The authors are grateful to their BCG colleagues Brett Spencer, Jacqueline DePasse, Kevin Hoffmann, Max Geraci, and Rise Miller for their assistance with this article.