A global contest for technological leadership is taking shape among the world’s major economies. Technology-based supply chains are increasingly forced to contend with rising geopolitical friction over national and economic security. Trade, which once shaped geopolitics, is now itself being molded by geopolitics.

The change comes as the world is witnessing a new, tougher business environment, with the COVID-19 pandemic, trade tensions, the war in Ukraine, and other disruptions putting the brakes on a long period of steady globalization. Under growing uncertainty, companies of all kinds must reconfigure global supply chains to improve their resilience. But technology companies face challenges of greater risk and complexity.

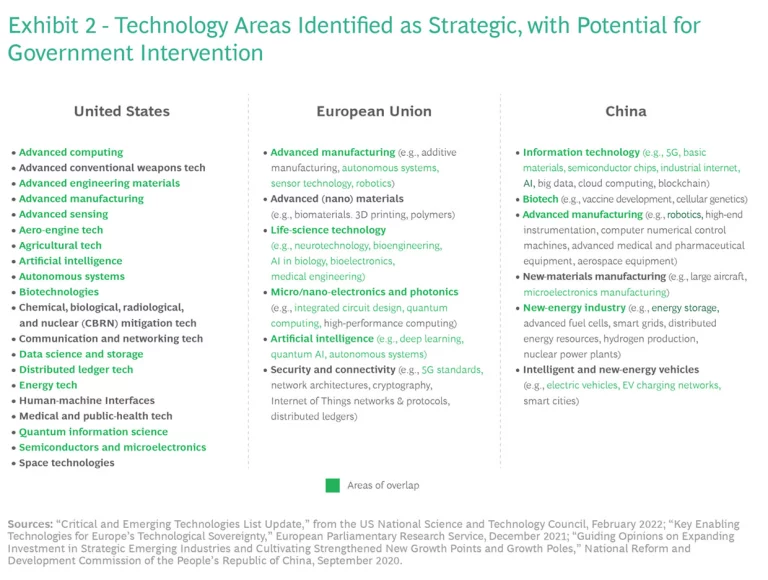

Major economies, such as the US, China, the European Union, Japan, and India, are increasingly sensitive to the economic and national-security importance of the most advanced technologies and are moving aggressively with policies to regulate and sometimes reshore technology supply chains.

As a result, companies that produce or rely heavily on strategic technologies must put geopolitical risk at the forefront of their strategic agendas to a degree that has not been necessary until now. To stay competitive, tech companies should not wait for detailed regulations to be rolled out. Instead, they should stay ahead of events by preparing playbooks to shape their intricate supply networks. The question is no longer whether technology supply chains will change, but how much and how fast.

Risks and Challenges for Technology Supply Chains

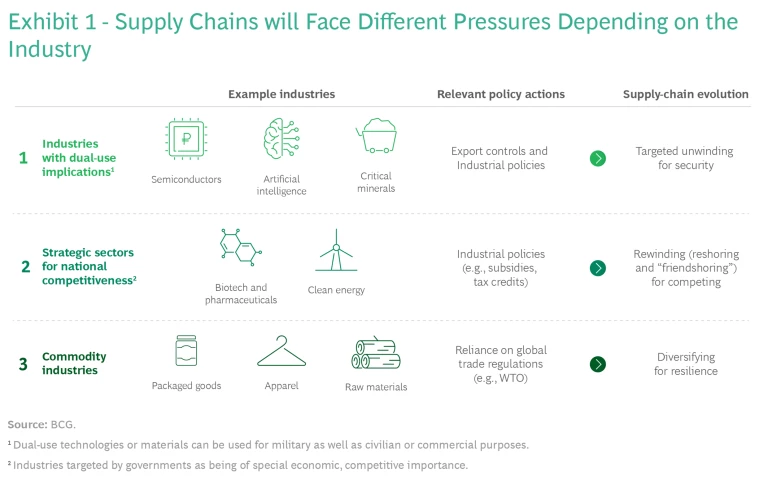

We believe players must prepare for a variety of risks that are likely to arise from government policies and customer behavior, depending on which of three segments the companies fall into. (See Exhibit 1.) To get ready for the new challenges, leaders should assess their companies’ supply chains using a few guiding principles.

- Industries whose supply chains have national-security implications—especially producers of dual-use technologies, such as semiconductors or artificial intelligence , that can be used for military as well as civilian purposes—are likely to be forced to change substantially. Other dual-use offerings include certain production inputs, such as rare earth or other metals and so-called critical materials, that can be used in both military systems and consumer products . Governments may pursue targeted policies to ensure security, geopolitical advantage, and resilience.

- Supply chains in areas deemed strategic, such as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and clean energy, may need to be reshored or built up from scratch in new geographies as governments aim for supply-chain resilience or economic competitiveness in sectors where innovation plays a large role.

- Industries without obvious national-security implications or strategic criticality (such as commodity-based industries) are likely to remain optimized for cost; however, to balance growth and resilience, companies in these industries may diversify their networks by sourcing supplies from other low-cost geographies. The only concern for industries in this category should be having their products disrupted in a broader geopolitical dispute, as has occurred in numerous past trade disputes.

Tensions over Technology

The global business environment is moving on from an era when market forces were the primary drivers of corporate planning. Now, national policies designed to incentivize targeted sectors and protect strategic technological advantages are increasingly prevalent. The result is a domino-like escalation where one country’s trade restrictions and industrial policies cause other countries to respond. Consider just a few examples:

- The US is implementing export controls to limit China’s access to the most advanced elements of the semiconductor value chain. Restrictions implemented in October 2022 curtail Chinese firms’ access to advanced AI semiconductor designs and chips above certain performance thresholds. They also limit access to manufacturing tools and parts for advanced chips, and to talent. Leading up to this, in August 2022, US President Joe Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act, providing $39 billion in incentives to promote semiconductor-manufacturing resilience. And in the fall of 2022, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said “computing-related technologies, biotech, and clean tech are truly ‘force multipliers,’” and “leadership in each of these is a national security imperative.”

- Meanwhile, China, in its 14th Five-Year Plan (launched in 2021), accelerated industrial policies for the domestic semiconductor industry. In October 2022, President Xi Jinping called for China to “cultivate new growth engines such as next-generation information technology, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, new energy, new materials, high-end equipment, and green industry” and to “speed up efforts to achieve greater self-reliance and strength in science and technology.”

- Elsewhere, the EU is expected to pass legislation in 2023 that aims to increase European semiconductor firms’ global market share to 20% over ten years. This effort would be backed by $30 billion to $50 billion in funding from public and private sources. As EU President Ursula von der Leyen said in 2019, “we must have mastery and ownership of key technologies,” such as quantum computing, semiconductors, AI, and blockchain. In addition, the Netherlands and Japan, generally following the US’s example, have implemented export controls targeting China’s semiconductor industry. Japan has also approved $6.8 billion in funding to support domestic semiconductor firms. And India committed $10 billion to incentivize domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

While there is plenty of uncertainty about policy specifics in the future, the direction of policy is clear, and companies with exposure need to move quickly to prepare. We believe that government incentives or interventions are likely to continue in three types of technology supply chains:

- Open-source AI and semiconductors

- Quantum computing

- Industrial technologies, such as clean energy and biotech

The Potential “Closing” of Open Source

Traditionally, the technology industry has benefited greatly from open-source software, such as Linux and its global community of open-source innovators. However, geopolitical competition and national-security concerns may threaten the “openness” of open source.

Many of today’s popular AI algorithms and frameworks are available as open-source software. Any data scientist can download software such as TensorFlow—a popular AI framework released by a US technology firm—and build AI models. A similar example is Volcano, open-source AI software released by a Chinese firm with contributions from numerous US firms. However, AI technologies are inherently dual use. An algorithm for spotting manufacturing defects can in theory be trained to help drones strike military targets.

Geopolitical competition and national-security concerns may threaten the “openness” of open source.

Certain nascent semiconductor technologies (for example, RISC-V) are also open source, and enable developers to design new chips. Entities in the US, China, and the EU have embraced RISC-V to drive innovation across sectors. However, as with AI, chips are also dual-use technologies.

Therefore, it is possible that policymakers will regulate open-source technologies. While open-source software is free, the code is typically hosted on company-owned developer platforms—for example, GitHub, the most popular platform for open-source software. In 2019, GitHub complied with US sanctions that prohibit developers from Iran, Syria, and Crimea from accessing open-source code. Given the current dynamics over semiconductors and AI, the possibility that governments will restrict access to open-source technologies cannot be ignored.

With Quantum Computing, a Quantum Leap in Risk

Quantum computing promises to revolutionize industries by solving problems classical computers cannot solve, in such areas as drug discovery and optimizing supply-chain logistics. Quantum computing could create $450 billion to $850 billion in economic value in the coming decades .

On the other hand, quantum computing could potentially overwhelm modern cryptography defenses, posing cybersecurity risks of calamitous proportions. Scientists have already demonstrated that quantum computers could penetrate today’s security technologies. Another risk is that quantum computing will be considered as inherently dual use.

Quantum computing could potentially overwhelm modern cryptography defenses, posing cybersecurity risks of calamitous proportions.

Given this risk, nations can be expected to take precautions by implementing export controls and other regulatory measures. Bloomberg reported that the US is investigating the use of export controls to prevent this technology from going to China. In addition, Axios reported that the White House is considering a ban on US investment in Chinese companies engaged in quantum computing. Today, private, public, and academic organizations often collaborate on this technology. Going forward, however, policy interventions could disrupt collaborative innovation.

The Return of Industrial Policy in Strategic Technology Sectors

Beyond what is commercialized today, governments see advanced technologies in certain emerging sectors as also critical to economic competitiveness and national security; clean energy and biotech are two examples. Governments have begun to consider industrial policy and trade restrictions in these areas. (See Exhibit 2.)

The 2020-to-2050 cumulative market for clean technologies (which enable electric vehicles [EVs], for example) could reach $24 trillion to $75 trillion, depending on the pace and scale of

transition

. Governments are embracing industrial policy that accelerates the low-carbon transition while rebuilding manufacturing. In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act took effect in the US, providing a $7,500 tax credit for EVs assembled in North America (including Canada and Mexico) that do not contain batteries or critical minerals produced in or by “foreign entities of concern” (including

Biotechnology is another key sector to watch. Driven by advances in computing, AI, and nanosciences, biotechnology promises to enable progress in sectors such as agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals. The emerging “bioeconomy” will help generate more than $30 trillion of economic activity over the next 30 years.

Estimates for China’s 2015-2017 government investment in biotechnology are up to $100 billion. Meanwhile, the US aims to foster innovation in biotechnology, with $2 billion in funding. Japan launched its first government investment fund dedicated to economic security, targeting biotech along with AI and quantum technology.

Recommendations for the Private Sector

Industry leaders must realize that the need to rebuild technology supply chains could arise suddenly and could profoundly affect their business. As the current mantra goes, “Every company is a technology company,” and every company must be cognizant of the policy issues facing its business. While the semiconductor sector has been the most prominent industry affected thus far, the scope and scale of supply-chain unwinding and rebuilding will soon spread.

Subscribe to our Business Resilience E-Alert

To prepare for these developments, private-sector leaders should pursue four strategies:

- Understand your suppliers’ suppliers. Although companies have operated in an interconnected web of global supply chains for decades, many do not have a full inventory of their suppliers, much less of their suppliers’ suppliers. Invest to assess the risks to your supplier base. Modern AI tools can review and monitor supply-chain expenditure data. Accelerate efforts to de-risk your supply base as many countries begin to implement export controls. Because open-source software is a likely area of focus by policymakers, understand your company’s use of this technology.

- Anticipate where policy is shifting and prepare for change. Ensure that your Government Affairs and compliance teams have the resources and technical skills to inform/influence policymakers effectively. Government Affairs teams must work cross-functionally with experts in law, R&D, cybersecurity , and supply-chain management to assess risks posed by policy interventions on technology supply chains. Prepare by building scenarios, with signposts that help decisionmakers recognize the direction of change. In addition, develop strategy playbooks that get exposed areas of the business ready for the future.

- Look for opportunities in new policies. Industrial policies can benefit companies that act quickly. Consider the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act, with its tax breaks for EV makers that source batteries from within the US. Tesla responded by shifting its battery-manufacturing operations from Germany to the US, and other battery makers have signaled similar intentions. Also, bear in mind that the era of just-in-time is over, and the era of just-in-case is beginning for many sectors. Create plans to expand manufacturing capacity or identify new suppliers in the face of policy shifts.

- Have contingency plans in place for your talent. One of the most novel aspects of the US’s regulations on semiconductor trade with China is a provision preventing US citizens and permanent residents from working for Chinese semiconductor firms. Traditionally, the flow of people in the tech industry has not been limited, but that is beginning to change, opening new areas of risk. For example, many companies have established R&D labs in multiple countries and pursued transnational private or public academic partnerships. Consider your exposure to such geopolitical risk and have plans in place for your workforce.

In a new era of supply-chain dislocation and uncertainty, companies must move rapidly to understand how they will deal with a potential need to unwind and reconstruct their technology supply chains.