As attention focuses on wars in Eastern Europe and the Middle East and mounting tensions between the world’s great powers, a structural shift in the global order has been quietly underway. Large developing nations are exerting greater influence in world economic affairs and are beginning to build alternatives to Western-led institutions.

At this movement’s core is a formal intergovernmental grouping known as the BRICS+. The grouping includes five longstanding members—Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa—as well as five that joined in January 2024 or have been invited: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Together, these ten nations account for around 40% of both crude oil production and exports. They also account for one-quarter of global GDP, two-fifths of global trade in goods, and nearly half of the world’s population. Adding another dozen nations that have applied for membership, including dynamic emerging markets such as Thailand, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, would raise the group’s share to one-third of global GDP.

The growing BRICS+ gives emerging markets the opportunity to align on global topics and new economic opportunities.

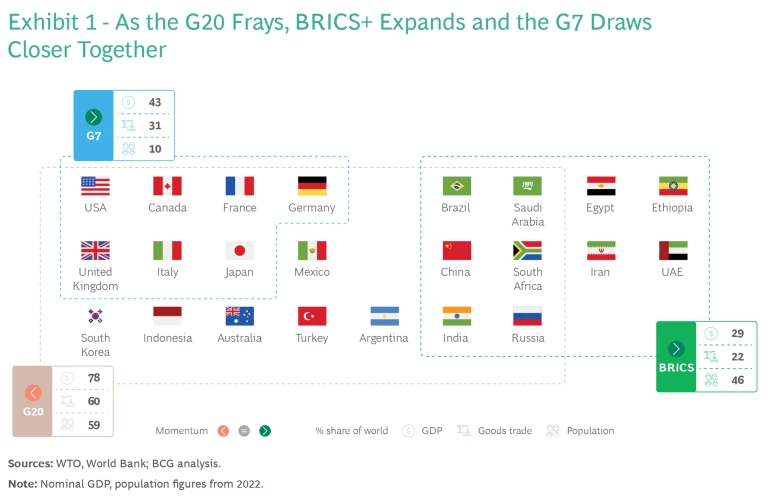

A larger BRICS challenges the dominance of existing global institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, that are strongly influenced by the West. It also further weakens the relevance of the G-20, a grouping founded in 1999 to seek economic policy alignment among the largest industrialized and developing economies. Indeed, the G20 is fraying at both ends: its seven most economically advanced members are strengthening their ties through the G7, while its six large developing economies are asserting their own voices within BRICS+. (Exhibit 1.)

BRICS+ creates a forum that, at minimum, gives emerging markets the opportunity to align on global topics and new opportunities to promote mutual economic development and growth. And it’s evolving steadily. As it begins building political and financial institutions and a payment mechanism for executing transactions, there are important potential implications for the future of energy trade, international finance, global supply chains, monetary policy, and technological research. As a result, global companies will need to factor these new geopolitical and economic realities into their investment strategies. They should also strengthen their capacity to capture the opportunities and to mitigate risk that they engender.

How BRICS+ Has Evolved

Leaders of the original BRICS nations held their first summit in 2009 to discuss reforming international financial institutions, which they believed did not adequately address the interests of the Global South. Aside from the United Nations and G20, which included all five BRICS, there was no major forum where emerging markets could discuss their own economic and geopolitical agendas. Development assistance and funding for infrastructure through financial institutions established largely by Western powers after World War II often came with challenging strings attached.

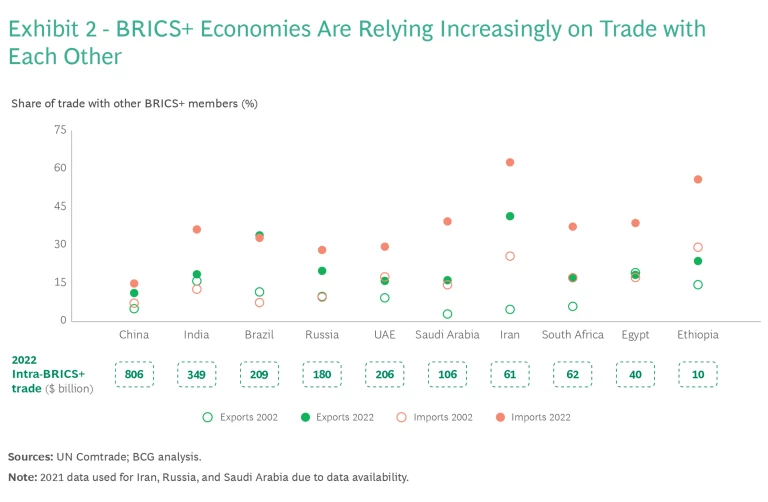

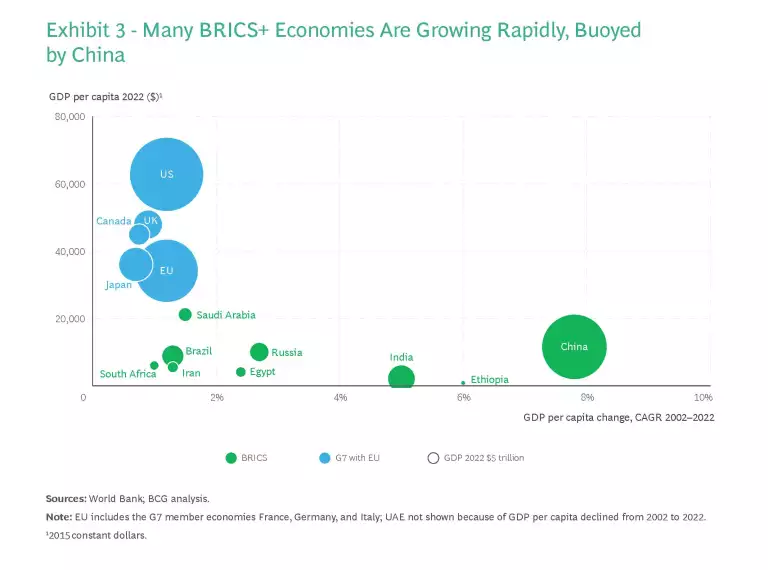

There has been skepticism from the beginning over whether BRICS would evolve into a functioning bloc. But over the years, these nations have been drawing nearer to each other economically. Trade in goods among BRICS economies has considerably outpaced trade between the BRICS and G7 nations, leading to greater intra-BRICS trade intensity. (Exhibit 2). Decades of rapid growth have also given many of these economies far more weight in the global economy, both as producers and consumers. (Exhibit 3.) Because many of these nations are engaged with both advanced economies and China, which is perceived as an economic and trade superpower, they can create another coalition less dependent on the West.

Recent crises have added momentum to BRICS expansion. Several big developing nations that are aligned with neither NATO nor Russia resisted pressure to adhere to Western-imposed sanctions on Moscow in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Others have complained that G7 nations’ initiatives to combat climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic did not take their needs into account. BRICS+ institutions have been slowly evolving through regular meetings, joint initiatives, and formal bodies.

Yet grounds for skepticism over BRICS+’s capacity to become an effective institution remain. This grouping includes countries that are very diverse in terms of political systems, institutional frameworks, economic models, and cultural backgrounds. It even includes geopolitical rivals; for example, relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as between China and India, remain strained. A so-called “China shock” of low-cost exports of everything from steel and chemicals to machinery could also raise trade tensions within the group. The expansion, moreover, is heavily tilted toward the Middle East, so further regional balance may be required as the group grows.

A stronger BRICS+ could have a significant global impact in energy, trade networks, infrastructure, monetary policy, and technology.

Five Ways BRICS+ Can Shift the World Order

BRICS+ could make a significant global impact in the following five areas.

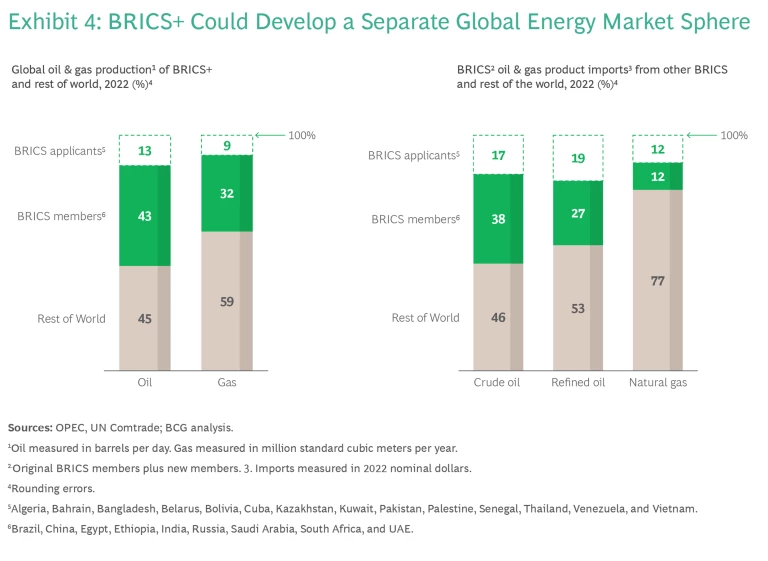

Energy. BRICS+ brings together both some of the world’s biggest energy producers and buyers. With the addition of Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, BRICS+ member states account for around 32% of world output of natural gas and 43% of crude oil. If Kazakhstan, Kuwait, and Bahrain are admitted, those shares will rise further. BRICS+ nations also account for 38% of global petroleum imports, led by China and India. If all new applicants are admitted, that would rise to 55%. (Exhibit 4.) During times of volatility in energy markets, having many of the biggest energy buyers and sellers within the same group could give rise to a parallel energy trading system. That would allow for transactions among BRICS+ economies outside the Western-led financial system and potential future sanction programs, and it would perhaps give them the ability to influence oil prices.

Trade networks. Trade has been a major driver of the economic development of BRICS+. The share of global trade in goods transacted among the group’s current members more than doubled, to 40%, from 2002 through 2022. This trend becomes clearer when looking at the increasing dependence of specific BRICS+ economies on trade with fellow BRICS+ members. China’s growing role as a supplier of industrial and consumer goods, as well as an importer of commodities, has been a key force for integration. China has become a major market for Brazilian soybeans and iron ore, for example, and a major exporter of advanced goods such as electric vehicles, solar panels, and heavy machinery. Western sanctions relating to the war in Ukraine, moreover, have led to the diversion of Russian exports to BRICS+ markets, notably China and India.

Although a handful of BRICS+ members have free trade agreements (FTAs) with each other through blocs such as the Gulf Cooperation Council and Pan-Arab Free Trade Area, there is currently no FTA covering the entire ten-nation group. India withdrew mid-negotiation from Asia’s Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which includes China. BRICS+ could, however, serve as a forum for widening intra-BRICS+ market access in various ways. It already convenes a Digital Economy Working Group, for example, and has established a framework for promoting cooperation in professional and business services trade.

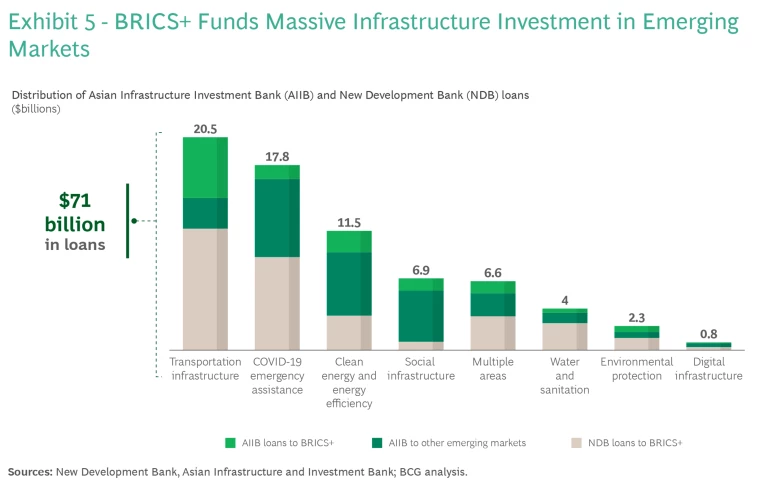

Infrastructure and development financing. The greatest progress so far in BRICS+ institution building has been in project and development finance. The New Development Bank (NDB), capitalized at $100 billion, largely complements China’s Belt & Road initiative. Egypt, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and UAE are also shareholders in the China-led Asian Infrastructure & Investment Bank (AIIB) and have received loans from it. By 2023, the NBD and AIIB combined had committed more than $71 billion in credit across a range of sectors, including infrastructure, public health, and clean energy. (Exhibit 5.) Such projects generate significant revenue for BRICS+ companies. The addition of Saudi Arabia and other cash-rich economies, moreover, could expand and diversify the financial resources of BRICS+.

Monetary policy. BRICS+ countries are keen to develop greater independence from the Western-led international monetary system. Approximately 90% of global foreign exchange transactions are conducted in dollars and flow primarily through US and European banks. Western financial sanctions on Russia underscored the powerful systemic influence the US still holds through Bretton Woods institutions and its central role in the global financial system. Because BRICS+ includes leading commodity exporters and importers, however, the group can become a conduit for foreign exchange transactions in currencies other than US dollars. The NDB, for instance, has issued about one-fifth of its loans in Chinese yuan. Russia, China, and other BRICS+ members also aim to promote digital currencies. The group has launched the beta version of a payment app—BRICSpay—that enables transactions in several non-dollar currencies. That could help nations ease reliance on the US and make them less vulnerable to sanctions and foreign exchange volatility during financial crises. From a governance perspective, BRICS+ has established the Payment Task Force, the Think Tank Network for Finance, and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, establishing a pool of reserves that can be used in place of IMF funds to help nations address financial crises.

Technological cooperation. Space is an overlooked dimension of BRICS+ collaboration. There is a BRICS+ Space Cooperation Joint Committee, supported by longstanding partnerships between Russia and China and China and Brazil. BRICS+ has also established a Partnership on New Industrial Revolution and a Center for Industrial Competencies. These initiatives aim to spur cooperation and innovation in leading-edge technologies in areas such as intelligent manufacturing, artificial intelligence, digitization, and clean energy. The efforts could help more emerging markets get in on the ground of new technologies, improve their capacity to create intellectual property, and adopt alternative technical standards.

Companies should consider response in BRICS+ market strategy, the infrastructure boom, China+1, risk and compliance, and geopolitics.

The Implications for Companies

An expanded BRICS presents risks as well as opportunities for business. Companies should anticipate that BRICS+ will develop more formal institutions and agreements in the years ahead and begin planning for such scenarios. Companies should consider action in five areas.

- Develop a BRICS-for-BRICS go-to-market strategy. BRICS+ markets are likely to experience significant growth over the next decade. While the group lacks formal trade and investment agreements, it already has substantial, growing intra-BRICS trade. BRICS+ markets could become valuable gateways for companies seeking to expand to other emerging markets. The success of China-made EVs in BRICS+ markets is a good example of how companies can customize offerings to reach consumers across the member countries.

- Leverage the infrastructure boom. BRICS+ is likely to see significant infrastructure investment, which will improve the business environment and connectivity. Transportation, digital communications, energy, and other projects will generate demand for global companies and provide opportunities for investors. The NDB, for example, is funding 15 transportation infrastructure projects across the Indian subcontinent.

- Adopt “China + 1.” Many companies are pursuing supply chain strategies that seek to strike a difficult balance. They want to keep leveraging China’s many competitive advantages in manufacturing. But they also need to mitigate risks, react to shifts in relative costs, and gain access to government incentives for reshoring or near shoring. In a more multipolar world, companies could consider building supply chains that can leverage the BRICS+ economies. That could make them more resilient to geopolitical and trade shocks.

- Refine risk and compliance. Economic sanctions, such as those stemming from the war in Ukraine, and US-China technological competition are heightening legal, operational, and reputational risks for companies. A recent BCG survey of 250 risk and compliance officers found that geopolitical risk is now a top-five concern, up 15 spots from a prior survey. Most sanctions have emanated from Western countries. In the future, BRICS countries could coordinate a mutual “non-sanctioning” posture while also seeking to avoid the Western-led financial system. Multinational companies should account for this scenario when managing their import and export global supply chains, exchange rates, third-party screening, and risk and compliance needs. While companies will need to comply with Western sanctions, they can do so in ways that don’t hamper potential BRICS-for-BRICs value chains.

- Build geopolitical muscle. During the period of relative peace that followed the end of the Cold War, business leaders had limited need to assert themselves in global political and security issues. These days, geopolitics is increasingly uncertain and volatile. Executives need to prepare for a wide range of scenarios that could impact their operations, supply chains, consumers, and brands. They need to factor geopolitics into their capital-allocation decisions and strategic planning. Leaders should also build geopolitical sensing capabilities across their business units, functions, and regional managements to balance business efficiency with risk mitigation.

Recent years of new geopolitical tensions, economic ambition and instability, trade wars, and a pandemic have clearly brought lasting, structural change and challenges to the business landscape we once knew. The growth of the BRICS+ shows that, after decades of strong economic development, emerging markets are now ready for a larger role in the world order, one that better reflects their interests. Companies that adapt to this movement will be more likely to thrive in an evolving era of multipolar competition.