Listen to this article

A narrative has emerged lately that US demand for electric vehicles (EVs) has hit a wall. In reality, EV sales grew 50% in 2023; the problem was that the industry had forecast 70% growth. As a result, inventory piled up and a “price war” ensued that dominated headlines. OEMs have since slashed production targets and delayed product launches. To add to the general sense of pessimism, customers continue to express concerns over high costs, unpredictable residual values, frustrating charging experiences, and poor range in colder weather.

These setbacks have left many people wondering what’s in store for EVs—particularly the next generation of vehicles, which are set to hit the market as soon as the next 12 to 18 months. Will these new vehicles be able to capture demand beyond early adopters and lay the path to a market share of more than 60% for EVs by 2032, as the Biden administration is currently targeting?

By our analysis, balanced regulation, broader vehicle-segment coverage, and a lower total cost of ownership compared with gasoline-powered vehicles support a scenario in which EV market share surpasses 40% by 2030. The big question is whether US consumers still want to go along for the ride.

To find out, BCG surveyed 3,000 consumers to understand the demographic profiles, attitudes, and barriers to EV adoption of those looking to purchase a new vehicle. We also estimated the potential scale of demand if OEMs and other stakeholders meet their expectations. Among our key findings:

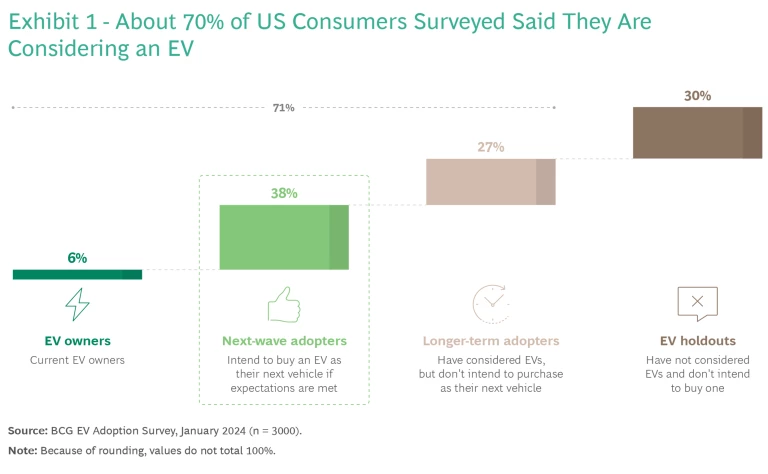

- In addition to the 6% that already own an EV, 38% of US consumers surveyed said they intend to purchase an EV as their next vehicle. Another 27% are considering buying one in the future. (See Exhibit 1.)

- To convert the next wave of adopters into buyers, OEMs must address these key median requirements: 20-minute charging times; 30-minute detour and wait times for fast-charging stations; a 350-mile driving range; and a price of $50,000. They’ll also need to offer greater vehicle variety.

- Meeting these customer expectations is possible, but OEMs will require support from both policymakers and the charging ecosystem—particularly if they expect to make money.

- If everything goes right, EV sales could account for up to 30% of US sales when next-generation EVs are in full production in the next few years. A more realistic scenario is that market share will be closer to 20%.

- In either scenario, hybrids will play an important role, accounting for a 15% to 20% share of US sales once the next generation of EVs are on the market.

Who Are the Next-Wave Adopters?

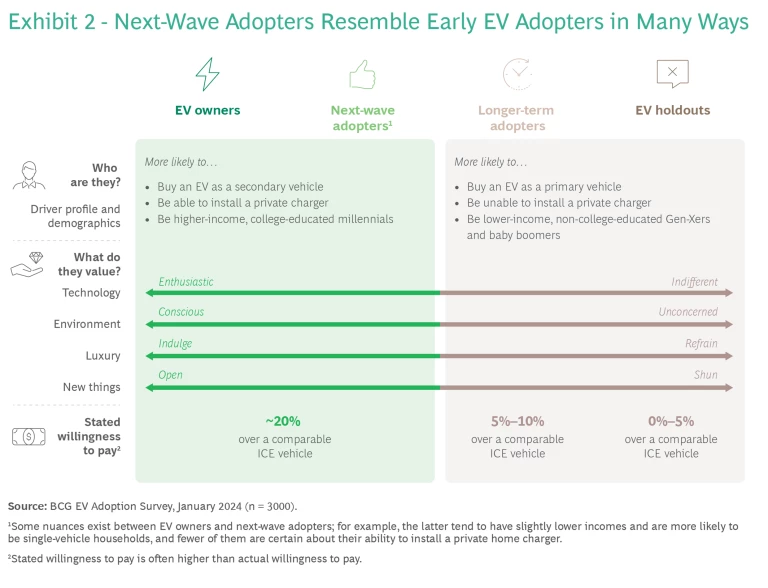

In many ways, the profile of the next wave of adopters resembles that of current EV owners. Most next-wave buyers can install chargers at home and are more likely to have a secondary vehicle. Demographically, consumers in both groups tend to be men who are college-educated millennials with relatively high incomes. Attitudinally, they’re less price sensitive, more enthusiastic about technology, and more likely to indulge in a luxury purchase than the overall US market. (See Exhibit 2.)

But OEMs must be aware of important differences in these buyers. Next-wave adopters place a higher priority on running costs and well-established vehicle brands than current EV owners. They also tend to be less interested in EV-centric features such as the “frunk” and tech-forward infotainment.

Are OEMs Up to the Challenge?

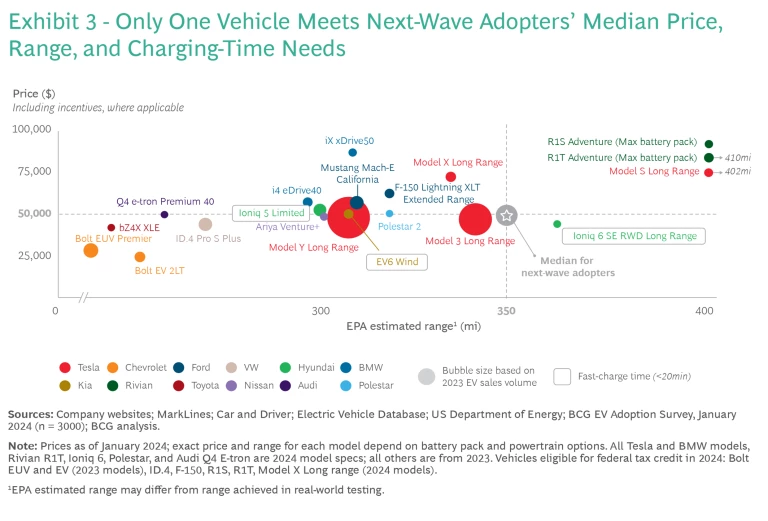

Only one vehicle available today—the Hyundai Ioniq 6, first sold in the US in March 2023—meets the median consumer thresholds for price, range, and charge time cited above. The Tesla Model 3, one of the best-selling EVs in the US, closely follows. (See Exhibit 3.)

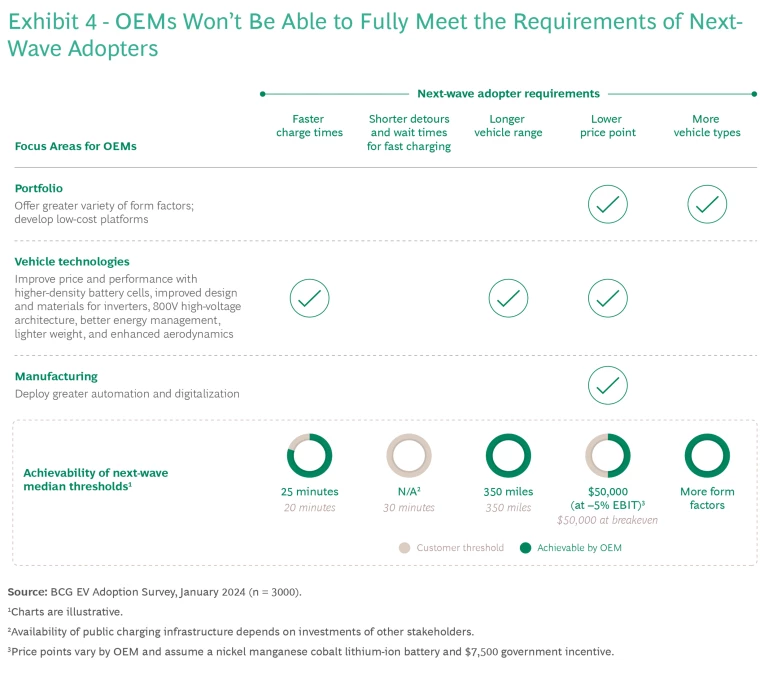

An encouraging finding from our research, however, is that OEMs appear to be capable of technologically achieving several of the median thresholds for next-wave adopters when they release their next generation of EV platforms. (See Exhibit 4.)

OEMs can make great strides in lowering charging times, extending range, and reducing costs. Progress is being made on high-density cell chemistries, more efficient inverters, lower-cost e-motors, 800-volt architectures for faster charging, and next-generation manufacturing automation. In addition, OEMs can make more efficient use of these technologies with more intelligent energy-management solutions that optimize battery usage and cooling and that minimize power losses. OEMs will also need to meet portfolio demands by introducing new low-cost platforms for the mass market and will need to leverage their larger platforms to meet unmet demand for three-row SUVs.

But perhaps the biggest challenge for OEMs is to produce the next generation of EVs profitably. We estimate that most OEMs currently lose around $6,000 on each EV they effectively sell for $50,000, after accounting for customer tax credits. We also estimate that OEMs will only be able to close half of this cost gap by making the right technology choices; economies of scale as automakers ramp up production will help, too, but they won’t make up the difference. Then there is the impact of looming Chinese imports to consider; market prices will likely contract further, exacerbating the profitability challenge. At some point, it will become untenable for OEMs to lose money on every vehicle they sell.

Closing the cost-profitability gap will require help from elsewhere, whether through more aggressive efficiency programs, additional public support, or both. Policymakers could consider linking financial incentives to total range and range efficiency to incentivize OEMs to invest in the areas that matter most to customers. The charging ecosystem will also have to find a way to smartly invest in making a network of 350-kilowatt chargers more readily available and reliable, recognizing that the demand for these chargers may eventually dissipate over the long term as vehicle range increases.

What Demand Can We Expect?

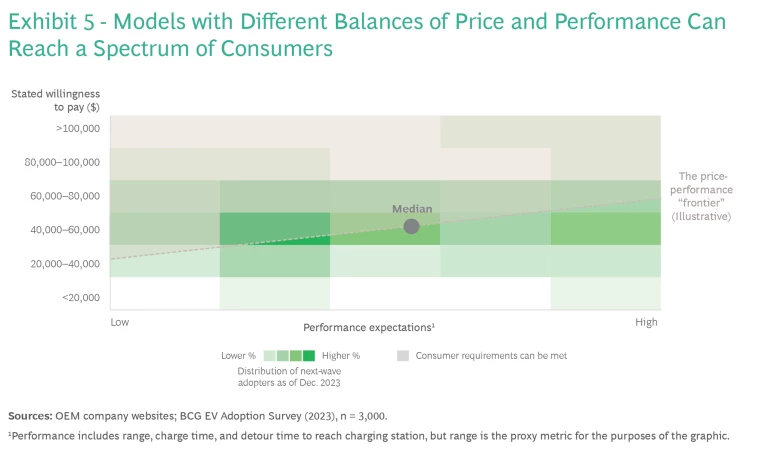

Much depends on the price-performance “frontier” that defines the tradeoff between price—which is driven primarily by battery and powertrain component costs—and range and charging performance. Generally speaking, consumers looking for extreme range and ultrafast charging should be prepared to pay a higher price; those looking for an inexpensive EV should be more willing to accept a shorter range. (See Exhibit 5.)

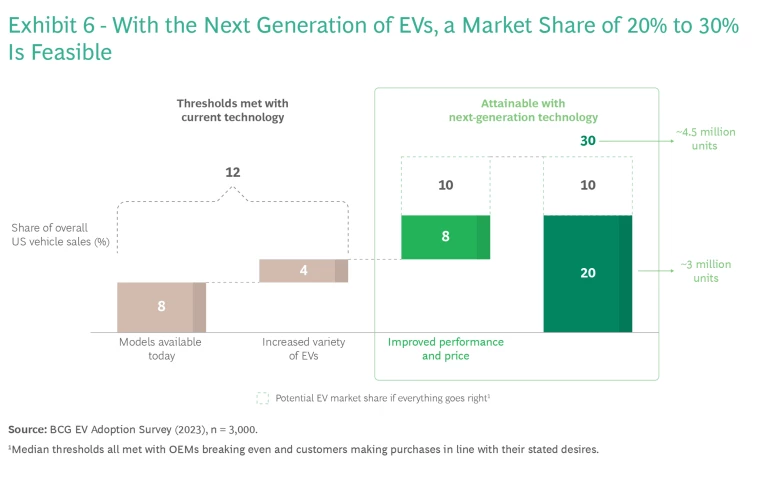

Using this relationship, our models indicate that up to 12% of car buyers can be reached with the technology available today. Our optimistic forecast is that up to 30% of US buyers can be reached when next-generation offerings are fully in production in the next few years; that represents potential demand of around 4.5 million units.

Of course, it’s not clear if all these conditions can be met. If OEMs can’t improve profitability, they are likely to delay launches and may hold off on the investments needed to significantly improve vehicle performance. Worries over battery degradation and resale values could scare consumers away from purchasing an EV—or those same concerns over resale values could push them toward the used car market. Under this more conservative scenario, we estimate that demand will be closer to 20%, or around 3 million units. (See Exhibit 6.)

What Role Will Hybrids Play in the Transition?

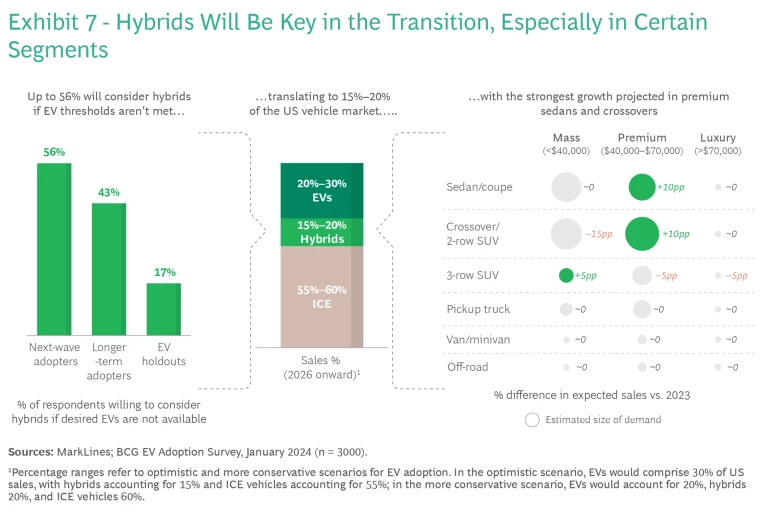

In our survey, 56% of next-wave adopters reported that they are willing to choose a hybrid if their needs aren’t met by fully electric vehicles. This compares to 43% for longer-term adopters and 17% for holdouts.

By our analysis, hybrids will account for 15% to 20% of new car sales when the next generation of EVs are on the market. Hybrid demand will be particularly strong in certain segments, such as mass-market and premium sedans, coupes, and crossovers. On the other hand, investment is likely less warranted in luxury and special-use hybrids, such as vans and offroad vehicles, because the total market size and growth are expected to be limited. (See Exhibit 7.)

A Call to Action

As OEMs look to win over customers with their next generation of EVs, they will be going after a group that, on average, looks very similar to current EV owners but has more demanding expectations for price and performance. Meeting their needs will be challenging, but not impossible.

OEMs will need to offer value propositions beyond environmental sustainability to compel consumer choice. This will require OEMs to develop a deep understanding of the specific needs of customer segments to differentiate their portfolios. OEMs will also need to invest in the right technologies and product portfolios while at the same time aggressively tackling costs. They will need stakeholders in the charging ecosystem to continue to invest in improving the charging experience. To do all of this profitably, OEMs will also have to rally policymakers for additional incentives.

With 70% of US consumers stating they would consider buying an EV, the market opportunity is there. But will OEMs and their shareholders overcome the profitability challenges and stay the course with the required investments? Will policymakers and the charging ecosystem step up to the plate? The answers to these questions will determine the pace of the US EV transition.

The authors thank Sean Chen, Kai Heller, Kristian Kuhlmann, John Pineda, Karen Lellouche Tordjman, Jonathan Nipper, Christoph Gauger, Albert Waas, Alex Wachtmeister, Alex Xie, Greg McRoskey, Christian Leavitt, Anoop Anoop, and Chekshu Puri for their valuable contributions to this article.