For the CEO

Will India be the world’s next great growth engine? It is a question globally minded CEOs cannot ignore.

India is currently the fastest-growing major economy on the planet, with some forecasts calling for it to overtake Germany and Japan to become the world’s third largest by 2027. Unlike its aging big-economy counterparts, over half of India’s 1.4 billion-strong population is under the age of thirty, priming it to reap demographic dividends for years to come. The ongoing realignment of global supply chains continues to work in the country’s favor, while its world-class digital public infrastructure is further distancing it from other emerging markets .

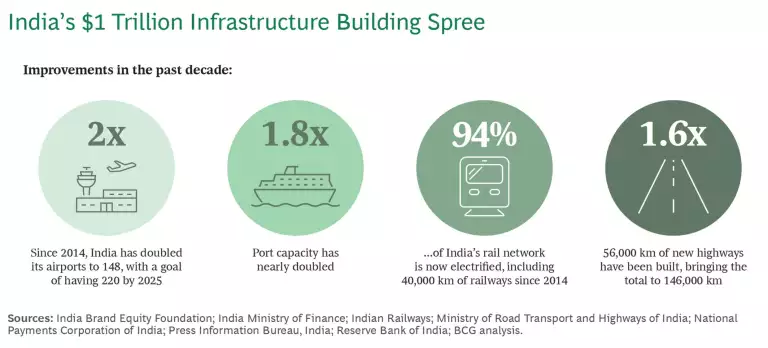

Throw in an infrastructure building spree, an upturn in the real estate market, and a more business-friendly policy environment, and the case for prolonged, sustained economic growth in India becomes even more compelling.

But for all its macroeconomic mojo, India’s granular complexities make it a tricky place to do business. “In India, the macro and the micro don’t talk to each other, and this traps a lot of multinational corporations,” says Janmejaya Sinha , a BCG managing director and senior partner and the firm’s India chair. “It’s getting easier to do business in India, but it’s not easy.”

FIVE ACTIONS FOR NAVIGATING INDIA SUCCESSFULLY

One reason doing business in the country continues to be tough, says Sinha, is that the states hold considerable sway over the business environment. “India has 28 states with double the population of the European Union but with the same level of complexity,” he says.

And like other fast-growing economies, India could stumble due to factors within and beyond its control, such as volatile energy prices, growing inequality, youth unemployment, insufficient urban infrastructure, or a poorly managed real estate cycle.

For now, though, the growth trajectory is trending up, and CEOs are taking notice. “I think India is much more on everybody’s radar screen,” says BCG global chair Rich Lesser , “whether it’s for their own operations, or to be a manufacturer—where India has enormous potential ahead—or as a source of business to sell within India.”

India’s growth trajectory is trending up, and CEOs are taking notice.

Moreover, companies that don’t have an ear to the ground in India could find themselves playing catch-up on new ways of doing business and reaching consumers—especially Gen Z.

“Digitization has allowed India to leapfrog on the business models and it has the largest Gen Z population in the world,” says Neeraj Aggarwal , a BCG managing director and senior partner and the firm’s Asia-Pacific chair. “The playbooks, which historically start in the West and come to India and trickle down, are now being coinvented here.”

Doing business in India is not for the faint-hearted. It’s a big country that demands big ambition. But CEOs today can learn from the mistakes of those who’ve tried before and been disappointed. With the right vision, actions, insights, and respect for India’s talents and uniqueness, CEOs can successfully unlock the country’s many burgeoning opportunities.

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

Commerce, Capability, Confidence…

While India’s economy has received a lot of attention lately, the country’s growth story has been unfolding for decades, with GDP expanding approximately 6.5% annually on average over the past thirty years, according to data from the International Monetary Fund. What makes this moment different, though, is nominal per capita income, which has steadily climbed from roughly $300 in the early 1990s to approximately $2,700 today.

“The 6% or 7% growth of today is different from the 7% growth of the 1990s,” says Neelkanth Mishra, chief economist at Axis Bank. “That was headcount driven; today, it is mostly GDP per capita.”

Multiple forecasts call for India’s economic output to grow from roughly $3.5 trillion today to $7 trillion or more by 2030. That outlook reflects the dramatic changes in India over the last decade. “One of the truths about India is don’t listen to projections,” says Sinha. “Listen to what has happened.”

Case in point: infrastructure. India has spent $1 trillion over the past seven years doubling its airports and port capacity, electrifying its railways, and building 56,000 kilometers of new

It’s not just India’s physical environment that has become more business friendly. The government has undertaken significant policy reforms to encourage consumption and bolster business activity. And then there’s the standout gamechanger—India’s digital public infrastructure.

“India is a mobile-first market,” says Kanika Sanghi , a BCG partner and director. “Consumers have become a lot more comfortable with digital over the last decade, the technology stack has been built out. It is time, therefore, to really leverage digital to leapfrog.”

The

digital transformation

is happening against a backdrop of enviable demographics. India’s median age is

India also enjoys a global tech-talent footprint no other country can match. Some 10% of global CEOs of high-tech companies have Indian roots; in addition to that powerful diaspora, India boasts roughly five million domestic STEM workers, and mints over two million new STEM grads annually. Little surprise it has the third-largest tech ecosystem in the world, with 31,000 tech-focused startups as of 2023—of which more than 100 were

“Something fundamental is afoot where there is money in the economy, commerce is changing, and there is capability in the people, further fueled by digitization,” says Aggarwal. “Also, the confidence of the next generation of entrepreneurs and people is changing.”

There is money in the economy, commerce is changing, and there is capability in the people, further fueled by digitization. — Neeraj Aggarwal

Global supply chains are also reordering to India’s benefit, as companies continue to pursue “China plus one” manufacturing diversification plans. A recent BCG analysis calls for India’s external trade to grow by $393 billion in the next ten years , citing its strength in industries such as consumer electronics, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

Closer to home, India’s improving real estate market should continue to power consumption. “The reason why the economy seems to be doing very well is that the real estate cycle has turned [up] again,” says Mishra. “The population growth has slowed below 1%, but the number of households is expanding at 2.4% a year because the household size is shrinking.”

The square footage of houses is also getting larger, and the quality is improving—all of which contribute to a virtuous multiplier effect that ripples throughout India’s economy as demand grows for building materials, fixtures, fittings, furnishings, and appliances. “Real estate in India should be a secular growth story for at least the next two decades,” says Mishra, who also sees significant opportunities in India’s energy sector as well as mobility solutions.

…and Challenges

For all it has going for it, India’s growth story could still experience some unfavorable plot twists. The country does not control its own energy supply, making it vulnerable to sudden price hikes if producers slash output or geopolitical disruptions upend global energy markets . The country is also severely water stressed. Its agricultural sector, which according to the World Bank contributes about 15% to India’s total GDP, is overly reliant on unpredictable monsoon rains. Nurturing growth will also require ongoing reforms to address pressing problems, such as expanding urban infrastructure to accommodate growing city populations. “The states don’t allow the cities to do what they should do, slowing down change,” says Mishra. “That, I think, is a massive challenge for us.”

India’s rising fortunes are also not accruing to everyone equally. The country has some of the highest levels of income and wealth inequality in the world. If it does become a $7 trillion economy by 2030, GDP per capita will still be less than $5,000, according to BCG’s Center for Customer Insight.

Widening disparities are not an unusual problem at this stage of a country’s economic development. What is unusual, however, is that India must address these disparities as the world’s largest democracy. “When you are not a democracy, there are ways that the state and the elite sort of manage the narrative around [income inequality],” says Mishra. “In a democracy, you have to deal with it; if policymakers in India cannot address it, reform momentum may slow.”

If policymakers in India cannot address [income inequality], reform momentum may slow. — Neelkanth Mishra

Another challenge: employment opportunities are not keeping pace with India’s growth, including in its IT services sector, where young graduates could formerly count on landing

But for all its challenges, India has more working for it than against it. “I think there is a lot of opportunity for entrepreneurs to deploy capital productively,” says Mishra. “Now, whether they’re able to compete with the locals or not is up to the CEOs.”

Where CEOs Stumble

Some multinationals have managed to create successful, category-leading businesses in India. But many companies lured by the country’s macroeconomic outlook have either failed to build significant businesses or given up and left.

Many factors can lead to disappointing outcomes, say experts, including a lack of dedication or aspiration.

“Without the tenacity and commitment, with full CEO support, to overcome India’s micro challenges, multinationals get frustrated and often leave,” says Sinha. “On the other hand, if they get stuck in the micro, they have low aspirations and build something small that is an insignificant share of their global business.”

Another common misstep, say experts, is trying to transpose a strategy that worked in another market onto India. “It’s a continent-sized country,” says Aggarwal. “It has its own playbook.”

The one-size-fits-all error doesn’t just apply to business models. Many multinationals tend to focus on New Delhi, believing it will be the gateway to a successful pan-India strategy. “It’s incredibly important to understand local market dynamics in India,” says Lesser. “Many states are as big or bigger than most countries around the world, and having local understanding, local relationships, is really important as you build out a team.”

It’s incredibly important to understand local market dynamics in India. — Rich Lesser

India’s consumers are also far from homogenous. “There are multiple regions and states and cultures within India, which are all very distinct from each other,” says Sanghi.

Purchasing power also varies widely. Some 12% of Indian households can currently be classed as “affluent” or “elite,” according to BCG analysis. Together, they represent 33% of total household expenditures. By 2030, though, the share of affluent and elite households is expected to grow to 25% and drive over half of all household spending, according to the Center for Customer Insight.

“For a long time, the understanding was that if you want to create a scale business in India, you have to target the mass because there aren’t enough [who are] affluent,” says Sanghi. “I think that is changing because it’s hit that critical mass.”

But thanks to digital infrastructure, there are also significant opportunities to reach consumers with more limited budgets. That is the thesis of Rama Bijapurkar’s book Lilliput Land: How Small is Driving India’s Consumption Story .

The mass market is not sitting around and waiting to grow up and be your consumer. — Rama Bijapurkar

“The mass market is not sitting around and waiting to grow up and be your consumer,” says Bijapurkar, an expert on Indian consumers. “The new economy has managed to crack the price-performance-profit conundrum altogether, and it has done that by aggregating small consumers, by aggregating small suppliers, by digitalizing processes and crashing costs.”

Bijapurkar further cautions CEOs not to fall into the trap of believing that price alone determines consumer choice in India. “They’re not bargain hunters. It is not the cheapest option that wins,” she says. “They have sophisticated—and unusual, for the western mind—value-processing algorithms that decide the option that offers the best value to them. That algorithm takes into account the benefits they perceive, how important that benefit is to them, and how they process price and cost of usage relative to other options.”

Another common mistake experts see multinationals make is micromanaging their local teams in India from abroad. “If you don’t trust [your local team],” says Sinha, “you won’t give them autonomy. And if you won’t give them autonomy, they won’t be able to customize for India.”

Finally, Sinha advises CEOs to think twice before taking their strategy cues on India from members of its diaspora who haven’t lived in the country for a decade or more. “You can’t claim to know India just because you were born here, or you have ties here,” he says.

Five Actions for Navigating India Successfully

Whether eyeing its markets for the first time, looking to expand an existing business, or bouncing back from a previous foray that failed to deliver, CEOs can improve their odds of launching successful businesses in India. Based on conversations with experts, the following five actions can help chief executives avoid common mistakes and turn the country’s unique characteristics and strengths into a business advantage:

Respect India’s uniqueness and aim high. CEOs who believe they can graft a playbook that succeeded in another market onto India may end up sorely disappointed. “There are still some CEOs who will make that mistake,” says Aggarwal. “Don’t come [to India] with your domestic mindset. Embrace the local, embrace it fully.”

That advice applies to business models and go-to-market strategies . “It’s important to ensure that both are designed for India,” says Sanghi. “Just replicating what exists elsewhere will not work.”

India will take the CEO time, and if the CEO is not willing to give India time, then India will frustrate the company and the CEO. — Janmejaya Sinha

Experts also advise CEOs to aim high—including those who may have healthy operations in India but, with greater aspiration, could expand them to become even more profitable. “You have to make it worthwhile,” says Sinha. “Because India will take the CEO time, and if the CEO is not willing to give India time, then India will frustrate the company and the CEO.”

Engage the states. India is a vast country made up of 28 states. “If you’re wanting to sell milk, there’s no point having a relationship in Delhi,” says Sinha. “You have to do it by state.”

That means building the organizational capacity to operate effectively within a target state, says Sinha. “You need people who can interpret, inform, and engage the state, and have a relationship at the appropriate authority level.”

Experts also advise CEOs not to overlook India’s less developed states. “I think real opportunities are now emerging in the hinterland,” says Mishra. “So, the poorer states—Uttar Pradesh or Odisha or Madhya Pradesh—these are states where you’ll be shocked at the infrastructure improvements, proactive governance, and therefore the rise in consumption capability. That’s where true reform is happening.”

Localize, localize, localize. India is a veritable forest of opportunities encompassing states, cities, income levels, and more. But it’s important for CEOs to know exactly which trees they want to shake. “Really segment India and understand who you want to target and design for that,” says Sanghi.

“I've often been asked, ‘Do I need to have such a multiprong strategy to win in India?’” says Bijapurkar. “And the answer is, you do, because it’s diverse.”

Companies do, however, need to be mindful to not err on the side of being too granular. “One of the challenges that companies face is you can’t localize too much, because then it creates too much complexity,” says Sanghi. “But then at the same time, you can’t just operate at the India level, because then you may not be appealing to many parts of India.”

For example, Sanghi advises companies to think beyond English-speaking consumers when designing for digital platforms and instead create something “bespoke” in vernacular languages. “English is spoken by a very small percentage of the Indian population,” she says. “If you create digital interfaces only in English, they will work for that small part of the population.”

Understand how Indians process value. Most Indian consumers are price-sensitive, and CEOs need to squeeze out savings all along the value chain. “Lazy businesses don’t make money in India,” says Aggarwal. “You need to be efficient in every part of the value chain—every part.”

But price is not the end-all-be-all of consumer choice. “A lot of the earlier generation of Indian consumers grew up in a scarcity environment, so their natural inclination was to save and not indulge,” says Sanghi. “If you look at the younger generations, they want to spend, they want to enjoy life as it is today, and not just save for the future.”

And multinationals who think they can brush aside local competitors do so at their peril. “Multinationals often believe that there is something called ‘world-class’ that they bring, which smaller companies in India don’t bring,” says Bijapurkar. “There is very strong local competition and small sector competition. They actually offer pretty good value to the consumer in terms of benefit minus cost.”

Empower your India office and stay agile. Micromanagement from abroad can hobble any local operation, and India is no exception.

“How can India be relevant [for a multinational] if India reports to Singapore, which reports to someone else, who then reports to the CEO,” says Sinha. “It gets lost, and India does not deal well with getting lost. It’s just too big. It’s too complicated.”

CEOs also need to give local offices in India latitude to create metrics capable of capturing the full story of what’s happening with operations in the country. “You need to adjust the metrics for cost and risk allocation for India,” says Sinha. “If you get allocated costs from the US or Germany, they often make it hard to measure true profitability.”

Local offices also need the freedom to attract top talent with an Indian-designed value proposition. “It’s not transactional, the relationship between the employer and the employee [in India],” says Aggarwal. “India has a lot of great talent, but you need to invest in nurturing them. You need to make them feel like part of the family, to give them a feeling that’s beyond just a brand.”

Finally, CEOs of consumer-focused companies should remember that India is awash with innovators who are leveraging its digital infrastructure to disrupt business-as-usual. “Organize yourself in a way that you’re nimble enough, agile enough to keep track of this rapidly changing ecosystem,” says Sanghi, “and orient yourself as the market reality is changing.”

At this moment in India’s evolution, the potential opportunities it presents to CEOs are too compelling to ignore. But while it’s getting easier to do business in the country, it remains challenging.

CEOs who believe India is just another emerging market they can conquer simply by focusing on New Delhi—or by using a playbook that worked somewhere else—are likely to have a rude awakening. The same is true of hesitant CEOs who lack the level of aspiration India demands. But CEOs can master India’s business landscape by respecting its complexities, empowering their local team, and working with the country’s considerable strengths.

Patricia Sabga is the executive editor of The CEO Agenda.