This article is part of a series examining the competitive outlook for key global process industries and how they can prosper in an uncertain future.

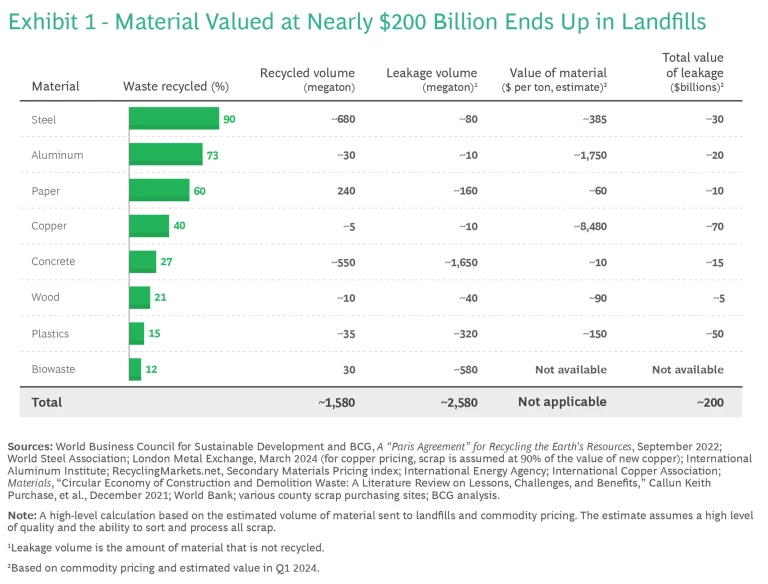

Each year, we throw away nearly $200 billion of material that could be recycled. Copper accounts for nearly $70 billion of that estimate; plastic, close to $50 billion.

Even if we can recover only half the value, those estimates highlight the business potential of circularity. Circularity is not just good for the environment. If companies can intercept waste before it hits landfills, it’s good for business too. (See Exhibit 1.)

By becoming circular, process companies (such as producers of metals, cement, and chemicals) can reduce volatility and other risks in their supply chains and lower costs, compared with their competitors. By solving critical

circularity

challenges, companies can differentiate their products and build stronger connections with customers and suppliers.

High Hurdles

Regrettably, the world is becoming less circular and more extractive. Only 7.2% of materials produced in 2023 came from circular sources, compared with 9.1% in 2018. The extraction of raw materials is projected to increase from 96 gigatons in 2000 to 167 gigatons in 2060. By 2030, demand will likely exceed supply for steel, copper, and aluminum.

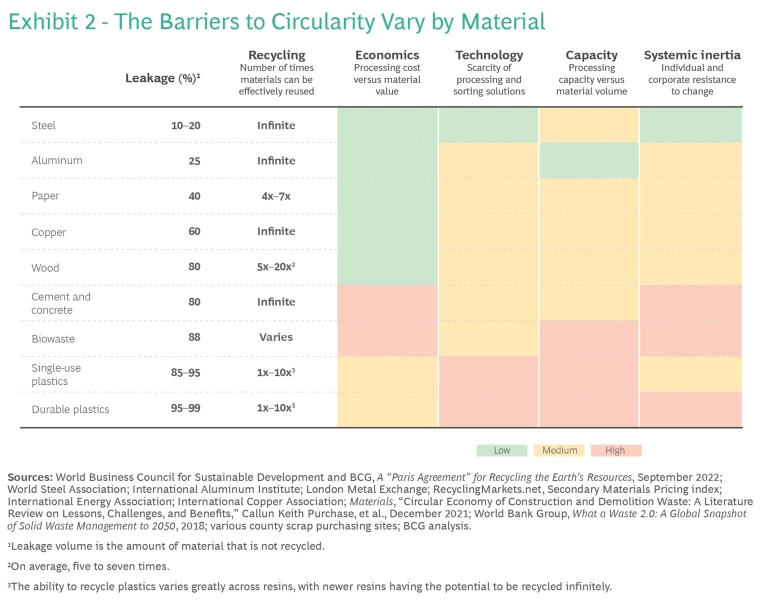

If circularity was easy to achieve, companies would have already embraced the concept. But barriers stand in the way. The barriers vary by type of material. They can include economic barriers if the cost of processing outweighs the value of the recycled materials, technical barriers if sorting or processing solutions are scarce, capacity barriers if there are fewer facilities than materials to recycle, and systemic inertia barriers if individual and corporate behaviors are resistant to change. Recycled materials will never fully replace virgin materials, but by improving the mix, companies can gain an edge. (See Exhibit 2.)

Circularity is like many other big societal and business challenges: there are limits to what companies can accomplish on their own. Recycling is an interdependent activity. To become more circular, companies need to partner and create ecosystems to help solve multiparty challenges such as fragmented waste-collection systems. Favorably, they have friendly tailwinds in the form of government support. (See “Regulatory Nudges.”)

Circularity’s Time Has Come

Regulatory Nudges

- Regulatory changes are encouraging local recycling and discouraging the export of wastes. The US Geological Survey’s Critical Mineral List restricts the export of minerals vital to national security even as wastes. China’s National Sword Policy bans the import of certain solid wastes. This rule has compelled countries to boost their recycling capabilities. The EU’s regulation on the shipment of waste promotes domestic recycling by limiting waste exports to non-OECD countries.

- Governments are also enforcing circularity through standards and directives. For example, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards require companies to disclose their efforts at sustainability. The EU also has more than ten directives encouraging circular supply chains, including the Critical Raw Materials Act and the Ecodesign Directive. In the US, extended producer responsibility regulations encourage recycling by making producers accountable for their products’ end of life.

- Significant public funding supports green initiatives that are crucial for the development of a circular economy. The US’s Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act together allocate $479 billion, primarily in tax credits, for climate and energy projects, including recycling. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provides $275 million in grants over five years authorized under the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act to encourage circularity and the reduction of marine waste. The EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan creates a $378 billion fund to stimulate a circular economy, while the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan makes €50 billion available to enhance circularity.

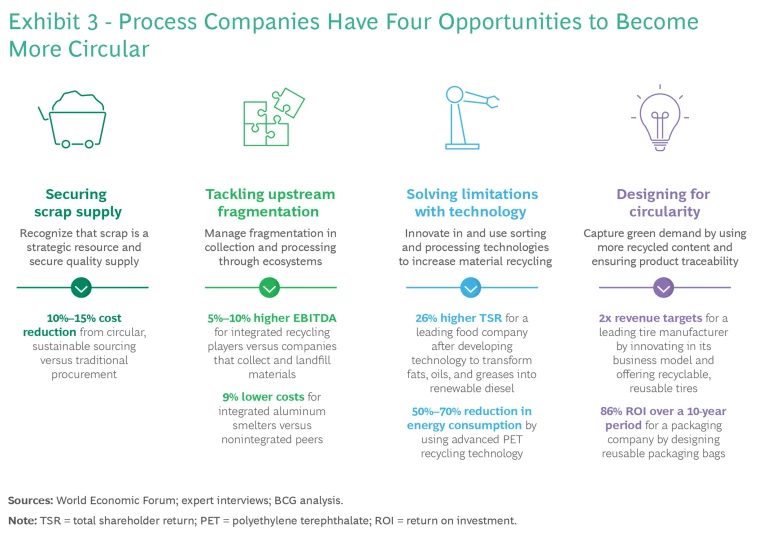

Four Opportunities

BCG has identified four lines of attack for process companies and others to pursue to become leaders and improve their resilience, economics, and early-mover advantages. (See Exhibit 3.)

Secure a steady supply of scrap. Companies in process industries such as steel, aluminum, and copper—where scrap has high value and potential shortages loom —will benefit by strategically sourcing steady streams of scrap and identifying ways to upgrade its quality. These measures could protect against the risk of rising prices and operational disruptions and lead to cost savings of approximately 10% to 15%.

The demand for steel scrap , for example, is expected to rise annually by 3.3% through 2030, outpacing supply by roughly 0.3 percentage points. Copper scrap faces similar shortages.

Export restrictions are creating bottlenecks that will likely exacerbate these shortages. Currently, 43 countries, particularly in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, restrict exports of various materials.

Companies can respond to these shortages and bottlenecks in several ways:

- Diversify supply sources through vertical integration and tapping into different regional and industry sectors.

- Establish strategic partnerships and acquire strategically located scrap yards to ensure a steady supply.

- Invest in infrastructure to collect and upgrade scrap, especially in areas with poorly developed circularity networks.

Companies that build circularity into their value chains can secure new feedstock flows that are inaccessible to competitors. For example, Novelis, a US-based aluminum supplier, has expanded its network of recycling centers to ensure its supply of scrap aluminum from companies in diverse industries. It has partnered with automakers to create closed-loop recycling systems that guarantee the return of high-quality scrap. Novelis has also collaborated with Sortera Alloys to improve the efficiency of the sorting and recycling processes for mixed-quality scrap.

By increasing the amount of recycled content in its products, Novelis has reduced its reliance on primary aluminum while cutting production costs and environmental impact. It has turned potential vulnerabilities into competitive advantages.

Tackle upstream waste fragmentation. The economics for recycling postconsumer material (including copper, paper, wood, and, to a lesser extent, aluminum) are promising but held back by two factors:

- A Fragmented Landscape. While larger regional players exist, the waste collection ecosystem is composed of thousands of local, subscale operators. Companies need to work with many operators to secure volume.

- The Quality of Supply. Waste streams often contain a mix of materials that originate from municipal, commercial, industrial, construction, and demolition sources. Companies struggle to secure waste material of sufficient quality from this pool of players.

If process companies can conquer these two challenges, they can tap into a large and growing market. The global waste recycling market was $60 billion in 2023, and it is expanding at 4% to 5% annually. In the US alone, the market for circularity-enabling services in collection and processing—including waste management, recycling, and energy recovery—is $9 billion.

Process companies that can create efficiencies and scale upstream will gain a consistent supply of recycled materials at lower cost. They should explore partnerships, acquisitions, joint ventures, and other avenues to improve upstream economics and ensure supply chain resiliency.

Umicore, a Belgium-based circularity, clean technology, and recycling company, grew from $2.6 billion in revenues in 2013 to $4.2 billion in 2023, in part through such partnerships and collaborations. To address fragmentation, it partnered to capture high-value material as it passes through concentrated points along the value chain. For example, in 2023 it launched a battery passport program with the Global Battery Alliance to trace batteries through their life cycle and assure their reuse. Umicore has also partnered with Audi, BMW, and other automakers to improve the recycling of batteries and their materials at the collection and processing stages of the value chain.

Spur innovation in sorting and processing technologies. For some materials, sorting or processing technology can be a bottleneck that prevents greater reuse. Aluminum, copper, paper, wood, and plastic are especially vulnerable to these bottlenecks.

With improved technology to handle contaminated and mixed materials, more of these materials can stay out of landfills. Upstream innovations can take two forms. Sorting technologies such as robots can separate valuable materials from waste, while processing technologies can improve converting scrap to virgin-quality material. Chemical recycling, for example, can handle less-sorted feedstocks and breaks down plastic waste into new materials.

To achieve circularity, the global economy requires more than $2 trillion in investments from 2021 through 2040. Most of that capital, or 57%, needs to go toward technological innovations in recycling and expanding recycling capacity.

Amp (formerly Amp Robotics) is a pioneer in developing advanced sorting technologies and efficient recycling facilities. The company combines machine learning with computer vision to deliver higher quality, higher throughput, and lower sorting costs compared with the results attained by human sorters when screening more than 50 materials. Other companies, including Tomra Systems, Sortera Alloys, and Steinert, are exploring x-ray and machine learning technologies, among others, to improve traditional mechanical techniques such as sink-float, electrostatic, and eddy current. Process companies that stay up to date and know how to deploy the best systems of technologies will get ahead.

Design for circularity. Circularity should not be an afterthought—the recycling crew brought in late to pick up the pieces and reuse them. It needs to be integral to a company’s strategy and operating model—a feature that can improve economics by lowering costs, capturing green demand, and giving a company a competitive edge in a commodity marketplace.

Demand for recycled products and green commodities is likely to exceed supply by 2030. Demand for recycled polymers, for example, is growing at 5% to 10% annually, more than twice the growth rate for virgin plastics. In many major value chains, the market share of companies with hard commitments to decarbonize their value chains far surpasses the share of upstream players that would need to supply the green materials to achieve these commitments. According to Winning in Green Markets: Scaling Products for a Net Zero World , this market share gap can be more than 20 percentage points for such materials as green plastics and chemicals.

Put simply, too many process companies are focused on the low-margin, high-volatility commodity end of the market and too few are designing for circularity. This is a missed opportunity. Process companies that incorporate circularity into their business models will gain through accessing new markets, diversifying offerings, and deepening their relationships with customers. They can create branded, differentiated solutions tailored to suppliers and customers; increase margins; and create customer loyalty.

Designing for circularity has two key elements: product design that encourages the use of recycled content and traceability to ensure the product can be certified so customers are confident of its provenance.

Scotch Cushion Lock by 3M was inspired by origami concepts and is an example of the first element. In the US, only about 5% of the polymers in bubble wrap are recycled. Scotch Cushion Lock is a fully recyclable paper replacement that stretches apart and crumples up into a protective cushion. The material also comes flattened in a roll, enabling lower transport and storage costs.

Hydro CIRCAL is an example of the second. Norsk Hydro, a $12.75 billion Norwegian company, uses novel supply chain technology and branding to differentiate aluminum products. Hydro CIRCAL is made from at least 75% recycled material, all fully traceable with a digital passport. These innovations have helped Hydro gain an edge in the market—as evidenced by its partnerships with Porsche and Vestre, a Norwegian furniture maker—to supply low-carbon aluminum.

The case for circularity has moved beyond reducing waste, preserving resources, or even mitigating supply chain risks and price volatility. Companies that are thinking so narrowly are missing the big picture. Circularity is an operating model that keeps on giving. Asking the following questions may help you understand your company’s performance on sustainability :

- What is our circularity ambition? Is circularity part of our decision-making process?

- Is my organization ready to pursue circularity? Do we know where we are strong and where we fall short across our operations and product portfolio? Do we have the right technology?

- Will my portfolio survive in a circular world? Do I know the requirements of my customers? How will sustainability regulations affect our business?

- Are we thinking about the commercial opportunities—such as introducing price premiums for green products or addressing specific customer requirements—in circularity, not just risk mitigation or environmental benefits?

- Where in the value chain is the bottleneck for circularity? How can we innovate our business model and capture value from solving these bottlenecks?

- How can we partner and collaborate with suppliers, customers, tech companies, and competitors to build a more robust circular ecosystem?

The authors thank Anna Albright, Santosh Appathurai, Miriam Benedi Díaz, Gaurav Chhibbar, Ari Flit, Jan Friese, Ryan Jones, Timm Lux, Maria Martinez de Lahidalga, Alex Meyer zum Felde, Lucyann Murray, Katherine Phillips, Marielle Remillard, Anish Thanatil, and Dave Young for their expertise and support in the development of this article.