This article is part of the 2024 European Consumer Sentiment Report series, which examines consumers’ shopping habits and preferences.

People in Europe feel more optimistic about their personal situation than about national issues, which has affected their spending practices, according to new BCG research on consumer sentiments, shopping habits, and preferences in the region.

We found that across the continent, 73% of people reported higher prices for goods and services in the first half of 2024, including for basics such as groceries, as well as for non-essentials, such discretionary items as clothes and toys. During the same time, salaries and savings stayed the same or dropped, leading people to compensate by spending less on non-essentials.

Consumers are taking steps to go green because of concerns about the environment, and a third of respondents think about sustainability when they shop. However, people see sustainability as less important than other factors, such as value and practicality, when making a purchase. As a result, only one in five say they would pay more for green products.

Going online to research a product or interact with customer service has become a standard shopping practice. But if forced to choose, people still would prefer to buy from a physical store over an online-only vendor.

European Consumer Sentiments Survey Findings

These trends are among the highlights of a consumer sentiment survey we conducted July 1–16 of 7,000 people in Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, and the UK. We asked people about current affairs and their personal lives in the first six months of 2024, their expectations for the rest of the year, and how both affected shopping habits and preferences.

People feel better about their personal life than about life in their country.

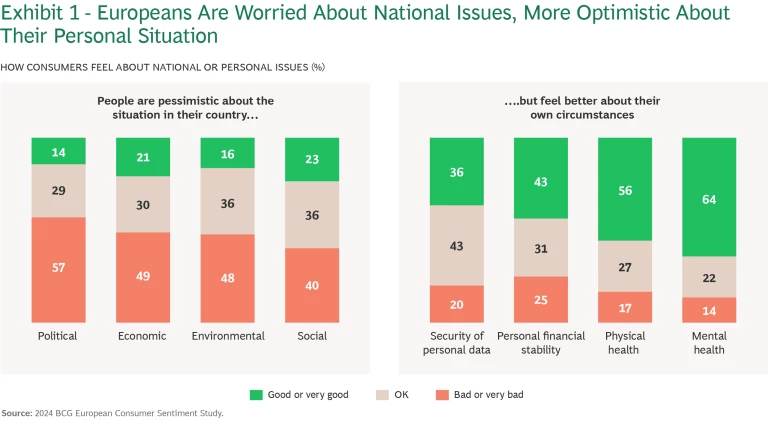

European consumers we surveyed said in the first half of 2024 they felt better about their personal situation than about national issues, including the economy, political situation, social and cultural atmosphere, and the environment. (See Exhibit 1.)

Residents of Nordic countries were slightly more optimistic about what’s happening in the region than the average. By contrast, people in France felt the worst about national issues among all survey respondents and were most concerned about the country’s political situation.

Price hikes caused people to spend less on non-essentials.

European consumers’ feelings about their financial wellbeing could be a reaction to the inflation that many have experienced. The vast majority of respondents (73%) reported paying higher prices for goods and services in the first half of the year. At the same time, wages and savings didn’t keep pace: 25% of people said their income dropped in the first half of 2024, and 28% said they didn’t save as much.

Higher prices affected spending, with close to four out of ten (39%) European consumers reporting that they spent more on basics from January to June 2024.

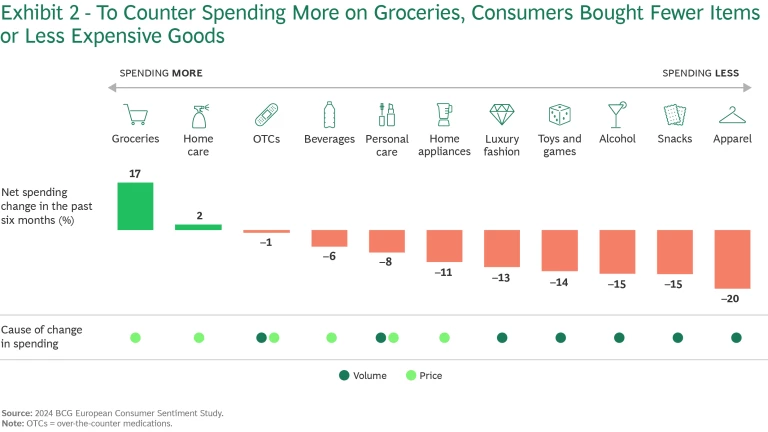

To make up for paying higher prices for basics, people generally cut their discretionary spending. They also bought fewer things and traded down to lower-priced brands. The product categories that experienced the largest net decreases included apparel (down 20%), snacks, and alcohol (each down 15%). (See Exhibit 2.)

Surprisingly, the net decline in spending on luxury fashion was not as severe as it was for apparel. The reason appears to be the existence of two distinct consumer groups. A more price-sensitive group cut what they spent by 35% during the first half of 2024. A second, more resilient group spent 22% more during the same period, primarily because they bought higher quality goods or more expensive brands.

Europeans are feeling slightly more confident about the future. The portion of people who expected price increases to continue through the end of 2024 was 59%—a significant drop from the 73% who reported paying higher prices in the first six months of the year. Only 22% expected to spend more on basics in the near future, and 26% anticipate spending more on non-essentials.

People care about sustainability, but value other purchase factors more.

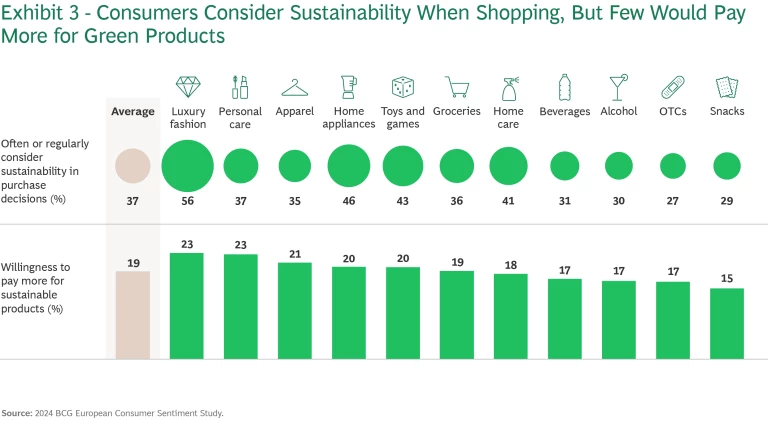

Close to four in ten European consumers said they occasionally or regularly think about sustainability and climate change when they’re shopping. (See Exhibit 3.) Awareness of sustainability does not automatically translate to a willingness to pay more for sustainable or green products. Nineteen percent of people said they would pay a premium for a green product. When they buy something, people still consider sustainability secondary to other, more important factors, such as good value, practicality, convenience, and offers or discounts that help them save money.

Shopping at a physical store still matters.

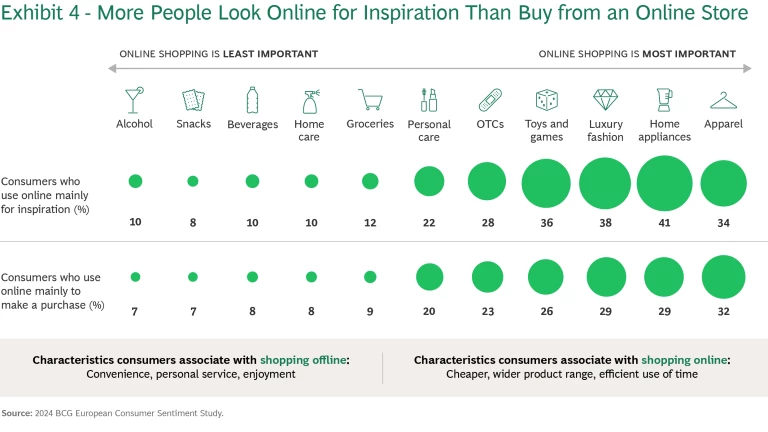

Most European shoppers said that, across all categories, they go online at some point during the process of buying something—whether to browse, look for inspiration, or complete a purchase. (See Exhibit 4.) However, they prefer to go to a physical store for regular purchases, such as groceries, beverages, and home care. Consumers view shopping online as offering lower prices, a wider product range, and a more efficient use of their time. But they see shopping at a physical store as more convenient, enjoyable, and offering more personal service.

In general, people prefer to buy online when they’re making big purchases or getting things they don’t buy as often, such as home appliances, toys and games, apparel, or luxury fashion. Even so, consumers told us that they consider online shopping superior for saving time, product availability, and promotions. People in France and Germany are the least likely to buy things online, especially when it comes to alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, groceries, over-the-counter medication, and home care items.

How Companies Can Respond to These Trends

To strengthen ties with consumers and stay competitive, companies should consider taking action in three areas: product assortment, pricing, and promotions. We’ve found that the impact is greater when companies launch changes in all three areas simultaneously. Due to the time and resources needed, however, most companies choose to address one area at a time. In addition, for changes to be successful, companies need a strong data analytics foundation. (See Exhibit 5.)

Localize product assortment.

Consumers are spending less, especially on non-essentials. Preferences for where people like to shop differ by country, and most residents in countries such as France and Germany still like buying in a physical store. To adapt, companies could customize what they offer in their physical locations to meet local demand and offer a more broad range of products on their e-commerce platform, which could appeal to shoppers who go online to browse or be inspired. In addition to increasing customer satisfaction, such changes minimize excess inventory.

A typical example of adjusting range is adding products that appeal to local consumers’ preferences or customs, such as halal or kosher foods. Other examples of more focused offerings are products from local coffee roasters or microbreweries.

Adopt dynamic pricing.

When consumers feel squeezed, they become more price sensitive. Companies could use data-based dynamic pricing strategies to counter shifting consumer preferences while improving their ability to respond to fluctuating volumes, local market conditions, commodity prices, and competition. Amazon is renowned for repricing books, electronics, wine, and other items multiple times a day based on inputs such as competition pricing, inventory levels, and consumer demand.

A leading European furniture retailer adopted dynamic pricing as part of a strategy to sell lower-cost items in order to respond to inflation and consumers’ desire for more affordable home furnishings. To manufacture lower-priced products, the company intensified its cost focus across the board, including for design, material development, production, and marketing . To make the new items affordable to consumers in its different regions, the company used an advanced pricing engine to adjust prices dynamically across sales channels and regions. The changes enabled the company to increase sales despite continued challenges in the furniture industry.

Make promotions hyper-personalized.

In addition to being more price sensitive and reluctant to buy non-essentials, consumers show less interest in loyalty programs relative to other shopping factors. Companies can counter such sentiments by individualizing loyalty programs and promotions.

Companies with successful programs use advanced analytics —including AI—to offer a level of personalization to loyalty members that other personalized promotions cannot match. The exclusivity that analytics-based promotions offer keeps consumers engaged and meets their need for good value and quality, making it more likely that they will keep shopping.

Nike’s membership program is a prime example of an AI-powered, hyper-personalized loyalty experience. People who download the free Nike membership app receive special access to exclusive products and experiences personalized to each shopper, free shipping, and more lenient return policies. In exchange, Nike collects consumer data from both the app and offline channels, which the company uses to improve its highly targeted, relevant promotions. For example, a Nike member who typically buys outerwear during the winter may get related promotions before the season starts.

Enhance data collection.

To successfully launch initiatives in product assortment, pricing, and promotions, companies must improve their ability to collect rich data on consumer behaviors and preferences across sales channels. Rich data includes consumer demographics, interests, and motivational drivers; what people buy, when, how, where, and why; and how they engage with sales channels, including through promotions or loyalty programs. If they revamp their digital presence and loyalty programs, companies can use the access they have to first-party consumer data to capitalize on customer relationships in ways that in the past were not possible.

Explore how these consumer trends are playing out at the country level.

Denmark’s Spending Dilemma: Cheerful Minds, Tight Purses

French Consumers Tighten Budgets, but See Better Times Ahead

German Consumers Are Cautiously Optimistic, but Not About Prices

UK Consumers Worry About the Economy and Spending

A Challenging Economy Forces Swedish Consumers To Spend Wiser

The authors would like to thank Mary Patrikiou and Martina Scrocco for their helpful comments and suggestions. They would also like to thank Megan Moore for conducting the research upon which this report is based.