The French construction industry is facing its biggest challenge in decades. Starting in 2020, a raft of new regulations have set aggressive targets for reducing the carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions of buildings and require construction companies—from architects to materials manufacturers to building firms—to adapt at speed.

These new regulations have had a dramatic effect on construction costs and property values—and have sparked heated debate in France. In new build, the rules require companies to use more energy-efficient materials and equipment. As a result, the cost of constructing a new building has risen by an estimated 10-20%, significantly slowing demand. In 2023, for example, building permits fell by almost 30% from the previous year.

For the existing building stock, French policymakers are encouraging green renovations through subsidies. But for those who don’t have the means to renovate their properties, the consequences are significant. According to a 2021 study by Notaires de France, which represents French real estate lawyers, properties with an energy performance rating of D or lower (not very efficient) sold for 10% less than equivalent properties with an A or B rating. Armed with such findings, detractors complain that the new regulations deepen the divide between those who can afford energy-efficient homes and those who cannot.

Other countries are watching developments in France closely. If the regulations are successful in reshaping the French built environment, governments elsewhere may adopt key elements to reduce their own buildings emissions—especially in Europe, where the European Commission is encouraging member states to move in the same direction. Understanding the benefits and challenges of this French experiment can help construction firms outside France to prepare for potential future regulatory changes in their own countries and steal a march on competitors.

The Importance of Reducing Emissions from Buildings

Buildings are responsible for about one-third of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. As a result, cleaner construction methods and buildings are essential for a greener world.

Despite the need for change, construction is a mature sector that has relied on the same materials and methods for decades. However, lowering emissions from buildings is emerging as a priority for policymakers worldwide. Regulations and industry initiatives aimed at tackling these emissions are set to shake up the global construction industry.

Buildings are responsible for about one-third of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

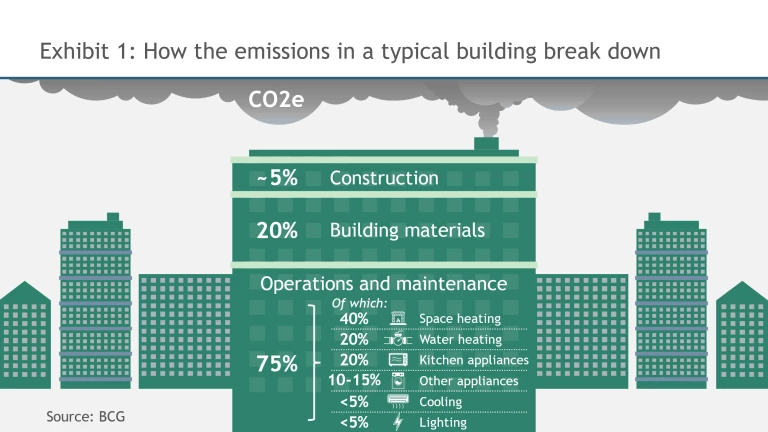

Emissions from traditional buildings are made up of three components (See Exhibit 1):

- Sourcing of materials, which accounts for about 20%;

- Construction, which makes up around 5%;

- Operations and maintenance, which together generate about 75%. (Emissions in this third category mainly come from space and water heating during the life of the building).

Regulators in Europe are ramping up efforts to curb emissions from new and existing buildings. The European Union’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, which was revised in early 2023, aims to achieve a highly energy efficient and decarbonized building stock by 2050. Among other measures, it asks member states to accelerate the renovation of high-emission buildings and introduces a zero-emission standard for new construction.

With its recent package of regulations, France has drastically changed the playing field for French construction companies and taken a significant leap towards meeting the requirements of the directive. Most other EU countries are currently studying how they can legislate to fulfil their obligations under the directive and testing incentive-based arrangements. But because of the country’s radical regulatory approach, France is also attracting the attention of policymakers outside Europe.

Why the French Approach Stands Out

France has taken steps to improve the energy efficiency of its buildings since the early 1970s. But over the last five years, new laws and regulations—including RE2020, the Climate and Resilience Law, the Tertiary Eco Energy Scheme, the Building Automation and Control Systems Law, and REP (Extended Producer Responsibility) regulations—have dramatically altered the landscape in the French buildings sector.

The main requirements of these game-changing measures are as follows:

Emission reductions: The industry must now meet far more demanding targets for cutting the energy consumption of new buildings:

- Construction & building materials: The construction of a single-family home is currently allowed to produce a maximum of 640 kilograms of CO2e emissions per meter squared—decreasing to 415 kilograms in 2031. These targets are a real challenge for the construction industry as players today struggle to reduce carbon intensity to such levels using current building materials and construction methods.

- Operations & maintenance: New single-family homes are restricted to emitting 4 kilograms of CO2e per meter squared each year—down from 50 kilograms of CO2e previously. Similarly, commercial buildings must reduce their CO2e emissions by 50% in 2040 versus 2010. These targets encourage deep shifts in the equipment used in new buildings. In the case of heating, the regulations are phasing out oil and gas boilers, and incentivize the installation of heat pumps. The use of energy measurement & automated control solutions is now mandatory in commercial buildings (but not yet in residential).

Owners of existing buildings must also take steps to improve the energy efficiency of their properties, e.g. by better insulating or changing heating systems. They face significant penalties otherwise: under the regulations, individuals and families that own the least efficient buildings are prohibited from renting them out. Because renovation has become a ‘must have’—rather than a ‘nice to have’—for owners wanting to generate a rental income, poor energy efficiency is increasingly reflected in property values, with a 10%-plus price difference linked to a property’s energy efficiency rating.

Summer comfort: New buildings must be designed to minimize the impact of heat waves during the summer months without relying on air conditioning (which consumes a lot of energy). This requires new approaches to building insulation and ventilation. For example, while windows in new buildings have been double-glazed for decades, window products with greater solar protection are gaining in popularity. Insulation requirements are also far more demanding to ensure that buildings maintain a cool internal environment during the summer – and a warm environment during the winter.

Renovation over construction: With about one-fifth of buildings either empty or used for rentals or as a second home (according to INSEE, the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies), France’s building stock is already big enough to meet the requirements of its population. As a result, the government’s decarbonization agenda encourages the renovation of existing buildings using green solutions rather than the construction of new ones. For example, property owners pay VAT at 20% for new building work, 10% for renovations, and just 5.5% for energy-efficient renovations.

In addition, the government has set restrictions on the development of new non-residential buildings. To help protect biodiversity and the natural environment, the construction of new commercial spaces over 10,000 square meters is prohibited if the surrounding soil is turned into an artificial surface.

Circularity: Under the Extended Producer Responsibility law, building materials manufacturers are required to make plans to collect and reuse, repair or recycle their products; for example, by financing eco-organizations responsible for collecting and sorting construction waste. Building materials player Saint-Gobain is a pioneer in this field. It collects construction site waste through its B2B distribution business Point P (via 60 recycling centers and hundreds of waste collection points) as well as its industrial business divisions. For example, Saint-Gobain Glass Recycling collects cullet—recycled glass which is re-used to produce either new float glass or glass wool. Similarly, Eqiom, a CRH company, has also launched recycling businesses: Ressourceo, which collects and recycles construction waste, and Sapphire, which turns waste from construction and other industries into clean energy. Sapphire is already helping to produce clean energy for three of Eqiom’s French cement plants.

How to Benefit from the New Regulations

Adapting to these new regulations has not been easy. The speed of change has sparked fierce debate within the French construction industry. Critics complain that both construction companies and property owners haven't been given enough time to adapt to the extremely demanding new targets. In addition, industry players fear that the new regulations will worsen the current downturn in the sector by pushing up the cost and the complexity of both new construction and renovation.

Overall, while the construction world has adapted to the targets set for 2022-2024, there have been numerous requests to slow down or revise the (even more ambitious) targets planned for 2025-2030.

Whether the French government decides to slow down the pace of change or not, we observe four key areas where best-in-class companies have succeeded in building a competitive advantage since the regulations were implemented.

Win the substitution game to capture market share: Companies that supply or use more sustainable building materials can benefit as these materials gain market share over traditional carbon-intensive products. Many construction companies are turning to wood and other bio-sourced materials to meet new regulatory requirements, pushing the demand for the entire sector up. For instance, Bouygues Construction, one of France's largest property developers, is targeting the use of wood structures in 30% of new projects by 2030. In the same vein, half of the Athletes' Village for the 2024 Paris Olympics will be made from wood.

Companies are also capitalizing on the potential of energy-efficient versions of traditional building materials. For instance, in 2022 Saint-Gobain launched Oraé, the world’s first certified low-carbon glass, Infinaé 13, a plasterboard containing over 50% recycled raw materials, and Weber Eco-Mortier, a mortar that incorporates recovered and recycled production residues for a reduced environmental impact.

Use the new market context to secure a price premium on green products: Companies that provide green building solutions should command higher prices for two main reasons. First, a supply and demand imbalance exists today in many green materials, creating green scarcity. Second, the price of a green product will not be driven simply by that of its gray alternative, but by the price of the next best alternative. Indeed, with each new building, the developer will have to choose the most cost-competitive way to achieve the regulatory targets. Although we’ve yet to fully observe this mechanism, the price of each solution should, in theory, be influenced by the cost of other solutions.

Identify opportunities to grow in adjacencies: Through innovation, companies can tap adjacent areas outside their historical strongholds—either in new products, new customer segments, or new geographies. For instance, in 2021 French group Legrand launched Drivia, a smart electrical panel that enables homeowners to control their appliances from their smartphones and help them reduce their energy consumption.

Be a first mover to secure green subsidies: Given the ambition and speed required by new green building regulations, governments are likely to provide support not just to homeowners and building developers but also to construction companies so they can make changes to their strategies and operations. In France, cement maker Eqiom secured financing from the government’s Innovation Fund for its K6 program, which aims to turn its Lumbres site into the first European carbon-neutral cement plant by using carbon capture. Similarly, competitor Vicat secured government support for its Argilor factory, which replaces part of the clinker required in cement manufacturing with clay. Smaller companies can also benefit from subsidies. For example, Deschaumes’s Naofloor reusable solid wood parquet flooring has been selected for the French government’s ETIncelle program.

Insights from This French Experiment

Players worldwide can learn from developments in the French construction industry so that they are better prepared for market changes ahead. We expect the following trends to emerge:

- Because of mounting pressures to be more environmentally friendly, construction will experience far greater disruption than in the past. Regulatory pressure will be the key to driving significant change. We expect other countries in Europe – and potentially further afield—to introduce bold new decarbonization regulations.

- First movers will gain significant competitive advantages. The biggest opportunities will appear within the first few years of new regulations taking effect, and we expect innovators to capture substantial market share.

- Fortunately, companies in countries outside France will have more time to prepare for change than their French counterparts had. They can use this time to their advantage. Indeed, players that actively invest in a greener future will be in a strong position when sector regulations catch up.

The jury is still out on whether France’s ambitious green building regulations will transform the country’s construction sector as deeply, and as quickly, as the government would like. Nevertheless, over the coming years, we expect other countries to pass regulations with similar objectives to France’s. Companies that plan ahead and invest for a low-carbon world have the potential to win big.