For the CEO

A conspicuous quiet permeates the corporate world lately—a trend all the more notable given that, not long ago, chief executives of the world’s largest corporations were airing views on a host of politically charged topics. In the US, company leaders raced to sign open letters protesting rollbacks of LGBTQ+ rights, advertised their support of Black Lives Matter, and even threatened to cancel investments in states that weakened voting rights. Many also spoke up about attempts to undermine the election in 2020 and the violent attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

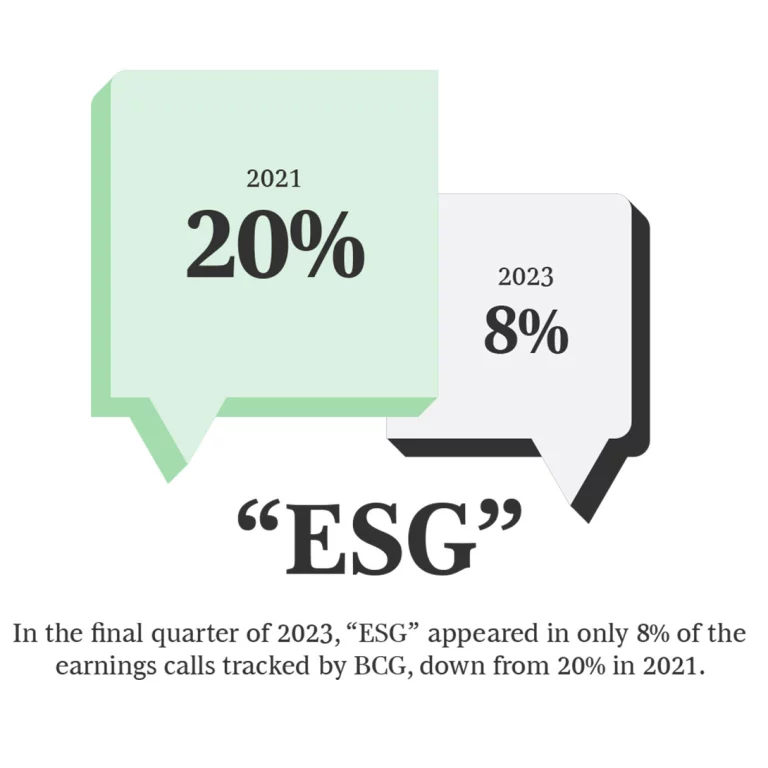

It’s not for lack of hot-button issues that C-suites aren’t as vocal as they once were. From reproductive rights and migration to the war in Gaza and the ongoing climate crisis, plenty of national and global events invite CEO comment. But increasingly, the public response from chief executives and the companies they lead are muted. Look no further than mentions of “ESG.” In 2021, the acronym appeared in 20% of the more than 4,500 earnings calls tracked by BCG; in the final quarter of 2023, it appeared in only 8%. “Diversity” and “inclusion” saw similarly sharp declines.

Corporate critics on the left and right of the political spectrum have the same explanation for what’s happening. In their narrative, chief executives who took public stands on environmental and social issues were motivated by commercial opportunism, not genuine conviction. When confronted by a concerted “anti-woke” backlash by conservatives and demands by progressives to back pronouncements with verifiable action, they ran scared—as shown by the rollback of some diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, declining investments in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funds, and the reversal of some fossil-fuel divestment pledges.

While this view has plenty of traction, it is not broadly supported by the evidence. Surveys and CEO roundtables conducted by BCG and other organizations over the past year suggest something far more nuanced is unfolding.

Explore the Five Ways CEOs Are Navigating a Polarized World

What emerges isn’t so much a picture of companies retreating from their core values and social and environmental commitments, but of companies recalibrating when and how to make their voices heard in an era of political polarization and viral social-media echo chambers. Instead of publicly reacting to events as they occur, CEOs are being more considered and strategic about speaking up on important but sensitive issues. They’re also being more cautious about making promises that are hard to keep.

C-suites and boardrooms were burning a lot of calories on issues and pledges, and that wasn’t sustainable. — Russell Dubner, Chief Communications Officer, BCG

“C-suites and boardrooms were burning a lot of calories on issues and pledges, and that wasn’t sustainable,” says Russell Dubner, BCG’s chief communications officer. “But except in cases where they’ve retrenched for legal reasons, you sense that more has changed with communications strategy than with the actual agenda: CEOs have lowered their voices.”

When weighing whether to raise their heads above the parapet with a public comment, CEOs these days are asking hard questions: Does the issue directly align with our business or core values? Do stakeholders expect us to take a certain stance? Do we have credibility with the target audience? How do we link our position to sustainable value creation for the enterprise? And if we do engage, can we actually make an impact?

Companies are also taking a more sophisticated approach to communications, spending less time touting their commitments and more on building the business case for them, documenting their actions, and explaining their positions directly to employees, customers, and other key stakeholders. They’re learning to avoid terms that have become politically loaded, subject to misinterpretation, or that anger key customer segments. And they’re building more rigorous mechanisms for addressing thorny issues and mitigating public relations risks.

The big question is how long this measured approach can be sustained, especially with pivotal elections approaching in the US and Europe. The possibility of dramatic policy changes and social unrest could soon thrust CEOs back into the hot seat to publicly defend the interests of their stakeholders and companies, and even potentially challenge how they communicate their own values.

Corporate Activism Then and Now

In the US, the high tide of corporate activism came in 2020 and early 2021. At the time, business leaders were under intense pressure to react to multiple developments simultaneously, including mass shootings, tough immigration policies, the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, state restrictions on voting and LGBTQ+ rights, and the 2020 election and its aftermath.

“These issues had a direct impact on employees, customers, investors, and executives themselves,” says Chris Deri, president of Weber Shandwick’s corporate advisory businesses. “But they also landed on the doorstep of C-suites with a magnitude they had never seen before, and at a time of highly polarized political discourse, compelling companies to communicate around issues they historically never engaged on.”

The 2020 police killing of George Floyd and the protests it ignited around the world was a watershed. “It was a very defining moment for corporations,” recalls a board member for several consumer-facing companies. “We saw both consumers and employees asking, begging, demanding that companies engage in a conversation because they had no faith that other institutions would be able to solve these kinds of challenges. Companies jumped into a whole set of social issues, all with the best intentions but often with unintended consequences.”

The reality is that business leaders wear two hats, especially in divided times like this. — Rich Lesser

Other than for a small set of socially and environmentally active CEOs, this degree of public advocacy was new to most large corporations. Many lacked policies, frameworks, and governance processes for deciding which issues to speak out on, let alone what to say. Nor did they make compelling cases to their investors and boards about how their public commitments aligned with their businesses or core values. “Business leaders probably spoke with good intentions,” says Craig Smith, chair in ethics and social responsibility at INSEAD. “But they weren’t thinking through the implications.”

As the conservative backlash against corporate activism grew, few companies were prepared. Florida, Texas, Indiana, North Carolina, and other US states passed legislation forbidding state agencies and pension funds from considering ESG factors in investment or contract decisions. Some brands that publicly marketed to LGBTQ+ consumers were hit with consumer boycotts. Companies that took stands against contentious legislation found themselves in the crosshairs of some Republican politicians, while the June 2023 Supreme Court ruling barring colleges from considering race in admissions decisions prompted some reassessments of corporate DEI programs.

These incidents are not isolated. Forty percent of companies surveyed by The Conference Board said they have experienced “moderate” to “very significant” backlash over their ESG policies. Nearly a third of companies that reported backlashes said they’ve reduced their external communications on environmental and social issues.

In the US, a number of state attorneys general and legislative bodies have threatened to sue financial institutions, alleging that their collaboration on net zero commitments and ESG goals violates antitrust laws. Congressional Republicans have launched antitrust probes, while the sheer volume of new legislation surrounding ESG, DEI, and LGBTQ+ rights is further compelling companies to be more selective about the battles they pick. As of early April 2024, the American Civil Liberties Union was tracking 484 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in 39 states.

Leadership by Design: Navigate the complexities of today’s leadership and management environment.

The Case for Companies Sticking with Their Agendas

While legal requirements have prompted some companies to change tactics, so far there’s little data to indicate that corporations are backing away en masse from their core values and positions on environmental and social issues. Two-thirds of the nearly 900 corporate board members in 19 industries surveyed in 2023 by BCG, INSEAD, and executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles said they believe sustainability should be more fully integrated into their companies’ business strategies.

In a January 2024 Weber Shandwick survey, 59% of senior executives agreed that companies “have a responsibility to speak up and act on societal issues even if sensitive or controversial.”

The strong business case for sustainability and diversity programs is one reason C-suites are not reversing course. Research shows companies that invest strategically in sustainability initiatives that are germane to their business can enhance shareholder returns by up to 5%. And key stakeholders still expect businesses to engage on important issues. Some 40% of directors in the BCG, INSEAD, and Heidrick & Struggles survey said ESG demands from customers, capital providers, and talent are growing.

Clients and customers no longer are satisfied with your promises to become carbon neutral by such and such year. They want you to have a plan to accomplish those goals. — Bruce Cleaver

Moreover, public expectations appear to have shifted little over the past five years. In a 2023 survey by Global Strategy Group, which tracks US consumer sentiment on corporate responsibility, and SEC Newgate, 79% of respondents agreed that “corporations have a responsibility to bring about social change on important issues.” That is below a peak of 86% in 2019 but a slight increase from 2020 and 2021, when the anti-woke movement kicked into high gear. Only the 15% of consumers identifying as “very conservative” disapproved of companies speaking out on social and political issues.

“The reality is that business leaders wear two hats, especially in divided times like this,” says Rich Lesser, BCG’s global chair. “Their primary role is to represent their businesses to the world. But at a time when people have lost faith in politicians, the media, and other institutions, CEOs are also perceived to have a parallel responsibility to be leaders in the broader community.”

Corporate leaders are also facing increased regulatory pressure on ESG issues. The EU now requires importers to report the entire greenhouse gas footprint for certain materials they bring into the bloc and will soon start assessing a carbon tax on imported goods. It’s also preparing to ban imports of certain agricultural commodities harvested from recently cleared rainforests as well as goods tied to child or forced labor and is set to require companies to perform due-diligence checks on supply chains for environmental and human rights violations. The US Securities and Exchange Commission is also seeking to implement more demanding climate-related disclosure requirements.

Meanwhile, activists are not letting up. Just as conservatives are becoming more litigious on ESG matters, so are NGOs determined to keep companies from backsliding.

How Business Leaders Are Recalibrating

CEOs and their teams are getting much savvier with their approach to sensitive issues. Drawing on lessons from communications successes and miscues, they are mitigating the risk of narratives spinning out of control and aiming to derive greater benefits from the public statements they make. There is also a growing body of research into what works—and what doesn’t—when navigating a polarized world.

1. Be Authentic

Companies that make their views on social issues well known over time—and back them with verifiable actions—tend to survive controversy better than those seen as jumping on a bandwagon. In a 2023 survey by The Harris Poll, for example, 77% of Americans said they “respect companies more if they’re clear on their values, even if they disagree with them.” This holds for companies whose values lean to either side of the political spectrum. Patagonia, which actively promotes its efforts in fair labor and environmental sustainability, has the highest Reputation Quotient score of 100 highly visible companies tracked by The Harris Poll. The fast-food chain Chick-fil-A, which is known for its conservative views, ranks fifth—and saw its reputation score improve in 2023.

“Organizations whose values are built into their DNA are weathering the backlash relatively well,” says Bobbi Thomason, an assistant professor of behavioral science at Pepperdine Graziadio Business School, who has written about the challenges business leaders face in addressing social issues. “But when statements come across as window dressing, companies are more likely to get called out and face a backlash.”

Many consumer products companies were accused of opportunism after they launched print and television ads supporting racial diversity during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. Critics pointed to their thin track records of speaking out on civil rights issues or histories of alleged discrimination within their organizations.

Impressive ESG scores and climate pledges are also viewed with increasing skepticism. More than half of people globally say they distrust company claims on environmental impact and ESG performance.

“Clients and customers no longer are satisfied with your promises to become carbon neutral by such and such year,” says Bruce Cleaver, former CEO of De Beers. “They want you to have a plan to accomplish those goals and be able to audit your progress.”

2. Make the Business Case

One clear outcome of the anti-woke backlash against corporate activism is that more companies are directly connecting their public positions on sensitive issues to their businesses.

In the Conference Board survey, 63% of companies that felt pressured over ESG policies said they’re focusing more on demonstrating how those initiatives translate into shareholder value.

“People are now for profitable sustainability,” says Paul Washington, executive director of The Conference Board’s ESG Center. This means showing how sustainability initiatives can secure a company’s future for long-term investors, especially at a time when climate change, the transition to nonfossil fuels, and geopolitical tensions are transforming the business landscape. “When companies invest trillions of dollars, you have to show that there will be a return over the long term,” Washington observes.

Companies can also emphasize the business case when taking a stand on social issues, including those related to DEI. When countering the narrative that these initiatives are “zero sum” and solely about assigning quotas or giving an unfair advantage to underrepresented groups, corporations can highlight “the tangible and measurable business opportunities for organizations that are diverse and where people feel included and psychologically safe,” says Nadjia Yousif, BCG’s chief diversity officer. She points to a BCG study of more than 1,700 companies globally that found that diverse workforces increase the capacity for innovation , and a separate BCG study that found that companies with inclusive cultures have lower attrition rates and higher levels of happiness, motivation, and well-being among all employee groups.

3. Be Consistent

Some of the hardest reputational hits have been dealt to brands of companies that surprised employees and other stakeholders by being late to speak out on topics important to them, sent marketing signals that were out of character, or abruptly changed their public posture when confronted. They often faced protests from consumers on both the left and right as a result.

“Stakeholders don’t have to agree with you all the time,” says Alexis Williams, chief brand officer of Stagwell, a marketing and communications group whose holdings include The Harris Poll. “But it is critical that companies earn their respect by living their values and staying consistent.”

Companies have also come under fire for falling short on public commitments that proved more difficult to achieve than anticipated, such as eliminating all child agricultural labor from their global supply chains, offering 100% recyclable packaging, or achieving net zero emissions by a certain year. “When you make a claim, you need to be sensitive to the fact that you are putting an extra target out there for activists to attack,” says Ron Soonieus, a BCG senior advisor and director in residence of the INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre.

4. Be Strategic and Tactical

A particularly painful lesson of the past few years is that even seemingly benign references to social or political issues can trigger brand-damaging reactions that go viral on social media.

These events have prompted leaders of many consumer product companies—particularly those targeting a broad market—to think longer and harder about if, when, and how to speak out on sensitive social and political issues. “If your company caters to a mass audience and can’t afford to alienate a big base of customers, it’s brutally hard to decide when to step in and when not to,” says the director of a company that’s been in the crosshairs of activists. “You’re caught between stakeholders who complain you’re doing too little too late and those who think your company has overstepped boundaries.”

Few corporate communications experts recommend that CEOs stay silent altogether on public issues important to their stakeholders. But they suggest several strategies for minimizing the risk of blowback.

One of the simplest adjustments regards nomenclature. Terms that were accepted a few years ago have been so politically weaponized they’ve become toxic, according to survey findings—even if the public generally agrees with the underlying principles they describe. A February 2024 Harris poll, for instance, found that 49% of Americans view the term DEI as “divisive” and 62% feel the same about ESG. Yet only 35% to 40% also regard “sustainability,” “equity,” and “inclusion” as divisive. Other polls have found overwhelming popular support for diversity in the workplace.

This discrepancy is partly due to misunderstanding. A 2023 Gallup poll found that only 36% of Americans are “somewhat” or “fairly” familiar with the term ESG, little changed from two years earlier. In a Global Strategy Group study, a mere 22% of Americans (and 20% globally) said they’re sure what the acronym stands for. That lack of clarity can make it easier for politicians and activists to hijack such a term to promote their agendas.

When they do feel compelled to speak out on issues touching core values, companies are increasingly taking steps to avoid the limelight. Rather than being in the vanguard, they’re seeking safety in numbers by working through business organizations. And instead of blasting out statements, executives are spending more time explaining their positions privately to stakeholders and policymakers. After some state governments threatened to pull state pension money from financial institutions with ESG commitments, several banks sent executives to meet privately with governors, legislators, and regulators to explain both their continued backing for fossil-fuel-based projects and the case for investing for the long term in companies with more sustainable business models.

5. Be Prepared

One reason corporate activism has cooled is that some of the most incendiary topics of a few years ago no longer dominate the news cycle. But with elections approaching in the US, Europe, and elsewhere, the calm is unlikely to last.

Changes in government could lead to sharp policy shifts concerning immigration, the energy transition, trade, and civil rights that directly affect businesses, employees, and communities. CEOs who are inclined to stay in the bunker could be forced out. “The big test will come after the elections if the policy dynamics change again,” notes BCG’s Dubner. “But with the stakes as high as they are, some CEOs may decide not to wait until after the 2024 election cycle to reengage on their core areas of focus, particularly with employees.”

Indeed, they may also face the dilemma of whether to address provocations aimed at voters before they head to the polls. CEOs “may want to think through how they would respond to major challenges preelection, such as large misinformation campaigns or threats of election-related violence,” says BCG’s Lesser.

To avoid communications missteps that erode consumers’ trust, strain supplier relationships, increase regulatory scrutiny, and hobble talent retention and recruitment, CEOs can make sure their company’s purpose and guiding principles are clearly articulated. They should ensure they have organizational capabilities and tools in place to monitor and analyze emerging hot-button issues that could disrupt their businesses and to gauge the sentiment of stakeholders. Companies should also devise scenarios for how topics could unfold, along with identifying developments that would trigger public statements.

Communications decisions should draw on input from across the organization with human resources, public affairs, consumer research, operations, and risk management weighing in. But the final call on when and how to publicly engage on sensitive topics should be made by the CEO, and in some cases, the board.

In a world of polarized politics and virulent social media, there’s little companies can say that won’t offend somebody and generate blowback. There’s no pleasing everyone. For better or worse, CEOs will continue to be under pressure to balance their two roles—as leaders of businesses and as leaders within their communities. With a thoughtful approach and measurable results, CEOs can sidestep most firestorms, boost credibility with their most important stakeholders, and ultimately advance commitments that make a real difference for their companies and the world.

Pete Engardio is a senior writer at BCG.