For the CEO

Few business topics generate as much heated debate as megadeals— mergers and acquisitions worth $10 billion or more. Enthusiasts laud them for reshaping the economics of entire industries, generating huge synergies, and turning midranking companies into global giants. Critics decry them as CEO vanity projects that destroy billions in value.

The reality is that megadeals can be a triumph or a disaster. In most cases, success largely pivots on the skills and mindset of the CEO and their senior leadership team . But the terrain CEOs must navigate to pull off megadeals is growing more fraught as the world becomes more geopolitically fragmented .

In recent years, governments have assessed takeovers—especially huge ones—with far greater scrutiny. Globally, the average $10 billion-plus deal announced in 2022 took 324 days to close, a 47% increase over the timeframe spanning 2018 to 2020. Potential policy shifts on the horizon could impact deal timelines further, elongating some while contracting others depending on the industry, especially where cross-border deals are concerned.

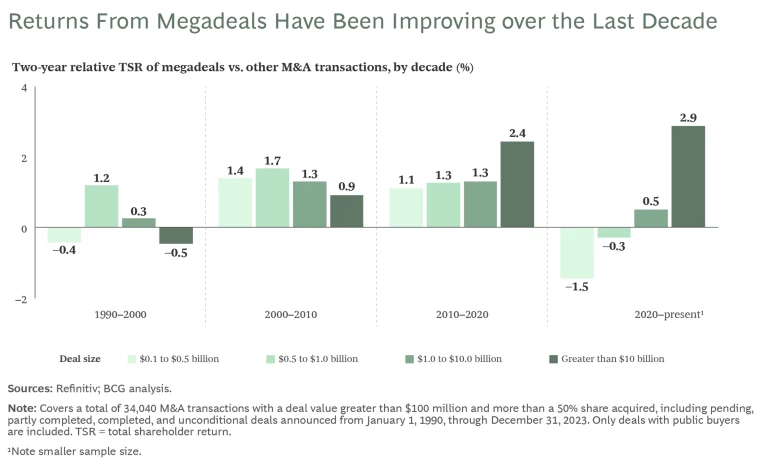

No matter which way the regulatory winds blow, CEOs are becoming more adept at overcoming the significant cultural, operational, and financial challenges inherent in large-scale corporate marriages. And they’re unlocking greater value from them. Megadeals announced this decade have yielded a two-year relative total shareholder return (TSR) of 2.9%—a notable turnaround from the 0.5% of the 1990s. (See the exhibit.)

“Larger deals can create enormous value and make a lot of sense for the company, shareholders, and consumers,” says Daniel Friedman , a BCG managing director and senior partner and global leader of the firm’s transactions and integrations business.

And such deals could be poised for a meaningful increase. BCG’s global M&A Sentiment Index continues to signal a steady recovery as interest rates ease globally, private equity buyers (who have plenty of dry powder) become more active, and the results from a slew of national elections inject greater certainty into the outlook.

Every corporate merger is a leap into the unknown, to some degree. But for leaders contemplating a megadeal in 2025, certain rules do apply—some of them universal, others specific to the current moment. Here’s what CEOs need to know.

Megadeals 101: The Immutable Rules of M&A

Some rules are steadfast and apply to deals of any size, such as the need to assess potential value creation under different conditions. Friedman compares these constants to “the laws of physics”—immutable rules of M&A that haven’t changed over time. And for large deals, they are even more important.

“The deal has to make strategic sense,” he says. “It has to have a real return on capital. There has to be a financial logic to the deal that is sustainable.”

For example, in-market deals are more likely to generate strategic value through scale and reduced costs, but they are more challenging to plan and more problematic for regulators. Deals done in a weak economy might seem daunting, but they slightly outperform those undertaken during an economic upturn. (See the sidebar “Dispelling the Myths.”)

Dispelling the Myths

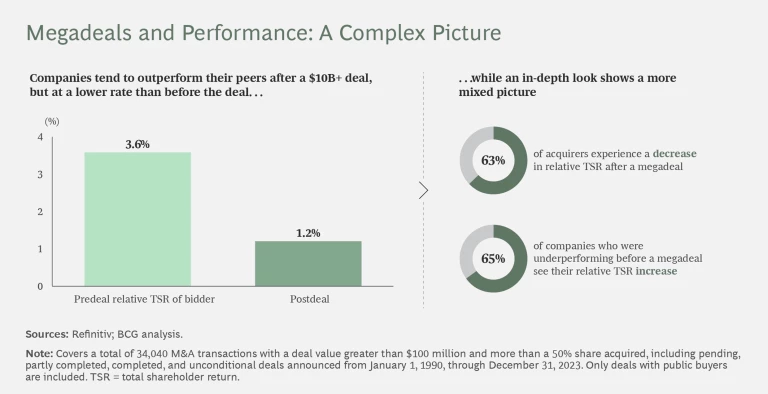

Myth #1: Megadeals usually destroy value. While that bad rap was somewhat warranted in the Barbarians at the Gate era of the 1980s and 1990s, it is no longer the case. BCG’s analysis finds that from the 2010s onward, companies that pulled off outsized acquisitions delivered outsized returns. Since 2020, the 2.9% relative TSR achieved by megadeals far exceeds the 0.5% TSR for deals valued at $1 billion to $10 billion over the same period.

Myth #2: No one is doing megadeals at the moment. In the first three quarters of 2024, 17 deals valued north of $10 billion were announced—slightly below the post-2010 average of seven deals per quarter. While M&A is not running as hot as 2021 and 2022, it’s nothing like the deal drought of the early 2010s.

Myth 3: Megadeals are a no-growth company’s last throw of the dice. Data shows that companies that launch megadeals tend to outperform their industry peers in the two years leading up to it. (See the exhibit.) That makes perfect sense. Outperformers are more likely to have the cash to fund a big purchase. If the buyer is paying with shares, higher multiples make a large deal more viable. That said, underperformers do worthwhile deals as well. Some 65% turn their negative, predeal relative TSR into a positive figure postdeal—underscoring how the right transaction can transform any company for the better.

Another steadfast rule: CEOs must plan the integration at the very earliest stage of the deal, when due diligence is taking place, and the board needs to actively monitor those efforts.

“It is very important that the board is on top of the value creation plan and whether it is being executed soundly,” says Teemu Ruska , a BCG managing director and senior partner and leader of its M&A, carve-out, and post-merger integration business in Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Africa.

Fully assessing the geopolitical implications of a deal has also become a hard-and-fast rule, says Ruska. “Geopolitics—where the factories are and where the markets are and where the supply chains are—plays a huge role in dealmaking nowadays.” Case in point, says Helsinki-based Ruska, are the Finnish companies that invested in Russia prior to its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and are now wrestling with a morass of trapped assets and lawsuits.

Finally, the longstanding rule of thumb for megadeals—to explore whether the same goal can be reached with a series of smaller, less risky transactions—is still relevant. (See the sidebar “Can AI Help Identify Deal Targets?”)

Can AI Help Identify Deal Targets?

“If you want to transform your company by purchasing a company that is going over $10 billion in size, it does not require AI to identify the target,” says Scott Moeller, professor at the M&A Research Centre at Bayes Business School in London and a former senior executive at Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley. “The companies that are megadeals are not hidden under rocks.”

AI can, however, be incredibly beneficial for stewarding a successful megadeal: crunching data for reintegration planning, finding overlaps in supply chains and production facilities to yield synergies, and tirelessly sifting through thousands of documents to perform due diligence.

“The best-performing companies are the ones that make regular acquisitions but on a smaller scale,” says Dominik Degen, global leader for BCG’s transactions and integrations knowledge team.

There are even options beyond M&A that CEOs can consider, such as licensing deals and other forms of contractual cooperation including nonequity alliances (such as joint R&D), minority investments, and

joint ventures

.

The CEO Checklist:

- The fundamentals of M&A still apply: deals need to make strategic and financial sense.

- In an era of uncertainty, look at geopolitics too.

- Megadeals can generate colossal value—but would a string of smaller deals work better for your company?

The New Rules for Megadeals

While some rules never change, the evolving business landscape inevitably introduces new variables—and with them, new rules for CEOs who hope to pull off a megadeal. Here are a few to keep in mind.

Expect Delays—and Take Advantage of Them

The higher the level of synergies, the longer it takes a deal to close, BCG analysis finds. But recent years have introduced additional factors that CEOs must consider .

For one, governments and regulators are putting a greater emphasis on national security and global competitiveness when assessing megadeals.

“There’s no question that across North America, Europe, even in Asia, in Japan, governments are much more interventionist around M&A,” says Friedman. “There’s much greater scrutiny, especially in large deals.”

US companies announcing megadeals from 2018 to 2020 waited, on average, 195 days to complete the transactions. By 2022, the average time was 323 days—four additional months. Asian acquiring companies saw an even more dramatic increase, with the average time from announcement to close more than doubling from 201 days to 452.

[Today] governments are much more interventionist around M&A. There’s much greater scrutiny, especially in large deals. — Daniel Friedman

Given the greater levels of scrutiny, companies pondering a megadeal should consider how regulators might assess it. This can help identify potential sticking points and concessions they can offer from the outset, such as selling a specific unit to avoid market-concentration issues. It can also help companies determine the maximum concessions they are willing to make. After all, too many sell-offs and other changes could destroy the strategic rationale for the deal.

It’s important to bear in mind, though, that longer timeframes do not necessarily work against a megadeal. “You may not want to design the whole organizational structure 12 months before the deal closes,” says Lianne Pot , a BCG managing director and senior partner and leader of its North American transactions and integration business.

CEOs can use this time to establish a “clean team.” Physically and digitally separate from both companies but with access to the data of both, a clean team can provide detailed analysis on sourcing synergies, customer overlap, or other key integration issues without compromising confidentiality.

You may not want to design the whole organizational structure 12 months before the deal closes. — Lianne Pot

“You probably want to know the operating model and how the companies will function together,” says Pot. “And then you can work backward from the deal close and say, ‘When do I actually start the detailed organizational design?’”

In a recent one-on-one interview with BCG CEO Christoph Schweizer , Douglas Peterson, former CEO of S&P Global, described how he turned an extended regulator-review process into an advantage as he led the biggest megadeal of 2020—S&P Global’s $44 billion merger with IHS Markit, which closed in 2022, some fifteen months after the deal was announced.

“I took a step back and said let’s take advantage of that [time] to come up with a plan for the strategy, the organization design, who are going to be the leaders across every part of the organization,” he told Schweizer in CEO Moments of Truth . “As opposed to many mergers and acquisitions, the day the deal closed, we had an executive team, we had the entire organization below them, and even a lot of the organization below them was already defined. So, we were able to move really fast after we closed.”

The CEO Checklist:

- Be prepared for delays, especially if there are significant cost synergies.

- Think of a delay as a gift, not a problem.

- Plan your plan: What needs planning first? What is best planned nearer the close?

Culture Matters More Than Ever

One aspect of megamergers that CEOs must give their time and energy to is how to successfully blend two corporate cultures.

“What really became apparent to me, and more obvious than ever, was the importance of culture,” Peterson told CEO Moments of Truth . “When you have two large organizations [S&P Global and IHS Markit] that are this big coming together, if you don’t put that front and center, it’s not going to happen.”

Satu Teerikangas, professor of management and organization at Finland’s University of Turku, says culture has long been an underappreciated success factor in megadeals. “We do brilliant legal analysis, technology analysis, financial due diligence,” she says. “Cultural due diligence is much more rarely done.”

Managers at global companies—which are the most likely to attempt a megamerger—often play down a culture clash, she says, believing there is a generic, global working culture. But Teerikangas’s own studies have shown, for example, that a German multinational company will have a very different culture than one based in another European country. Companies may also have many internal cultures rooted in previous incomplete integrations.

And given that job security stress, fear of change, and general dissatisfaction can permeate an organization in the throes of a megadeal, unnecessary conflict could result in the departure of staff vital to the newly integrated business—perhaps even into the arms of a rival company.

We do brilliant legal analysis, technology analysis, financial due diligence. Cultural due diligence is much more rarely done. — Satu Teerikangas

Recognizing a cultural issue is the first step to solving it, says Teerikangas. Communication is step two. In some cases, formal introductory sessions may be necessary to explain specific cultural disconnects. One example she offers: employees from the US or UK should be warned that German employees can consider the use of given names (calling someone “Max” instead of “Mr. Mustermann,” for instance) as patronizing and even rude. One case study she performed on a major European merger demonstrated how cultural issues like this created “a dynamic of continuous misunderstandings and miscommunications and disrespect.”

She also advises that while HR is an integral part of the solution, managers across the organization will need to do their part. “It’s something that cuts across all functions. So, it’s for every department, function, and unit to think about,” says Teerikangas.

Companies worried about talent could consider retention bonuses, says Pot, especially if there is a prolonged period of uncertainty. But clear communication about the future shape of the integrated, postdeal company can be even more effective. “In my experience, especially for more senior people, they get more motivated by a new role and the vision of the combined company,” she says. “They ask, ‘Do I want to work here?’ That’s more important.”

The CEO Checklist:

- Think about culture early. Recognize that it matters.

- Focus even more on culture for growth deals, where talent is particularly important.

- Communicate. Then, communicate again. Offer training if necessary.

Timing Is Everything

“The typical mantra in the industry is that time is the friend of the target company and the enemy of the buyer,” says Scott Moeller, professor at the M&A Research Centre at Bayes Business School in London and a former senior executive at Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley. “But the real picture is more complex than that, with some factors pushing a deal faster and some holding it back.”

The most common timing mistake is announcing a deal prematurely, says Moeller. “The longer the planning for an acquisition, the more likely you’re going to be properly thinking about the integration.”

He advises CEOs take their time when announcing a deal. While that may raise the risk that another firm may buy the target or make transactions that destroy the deal logic, such as divesting a prized division, “the fact of the matter is, it’s not buying the company that is the measurement of success,” says Moeller. “It’s what you do with the company after you buy it.”

He further cautions against keeping preplanning confined to too tiny a group. While it may diminish the odds of a potential leak, it can also reduce the quality of decisions.

Finally, when the deal is announced, CEOs should not be overly focused on the initial stock market reaction. “I don’t think there’s always a perfect view from the stock market around the full value-creation story and the vision of the combined company,” says Pot.

The real value creation, says Degen, often manifests a year or two or three after the deal closes, when synergies are unlocked—or not.

The CEO Checklist:

- Don’t rush the planning.

- Better to have no deal than a poorly planned one.

- Don’t be fazed by the stock market’s knee-jerk reaction.

Get It Right on Day One (and Day 1,000)

The journey to closing a megadeal can be long and arduous. But the last thing CEOs should do at that stage is dial down.

“If you make a megadeal and then let the acquired company just live its own life for a while after closing, you lose out on the biggest opportunity for change,” says Ruska. “You shouldn’t underestimate the value of the change window that you have.”

Significant change should not only be planned for the new acquisition, he says. It’s also an opportunity to make substantial changes in the acquiring firm.

This goes beyond Day One fundamentals such as email addresses, logos, and core legal work. Most companies manage to get that right. The big challenge is moving quickly to drive deep, high-quality integration, informed by strong team involvement. That’s why integration planning needs to start as early as possible in the deal process. Ideally, both companies, by deal close, will know each other intimately, and the new operating structure and teams can be put in place with maximum speed.

If you make a megadeal and then let the acquired company just live its own life for a while after closing, you lose out on the biggest opportunity for change. — Teemu Ruska

If a deal is driven by synergies, then there is usually good planning around that, says Ruska. However, many other critical and complex issues, such as merged supply chains or moving customers onto standard legal terms, are long-term projects that need to be tackled immediately to establish momentum.

Pot recommends using phased milestones to benchmark and drive progress: What can be done on Day One? When can HR and payroll be integrated? When can customers be moved onto one platform? Bear in mind that some of these may extend long beyond the traditional two-year postdeal integration horizon, particularly in financial services. “I don’t think there’s a magic number of two years,” says Pot.

The CEO Checklist:

- Generate momentum on Day One.

- Seize the opportunity to reshape your own company, too.

- If a two-year plan isn’t long enough, make a longer one.

Megadeals have always been risky. The current regulatory landscape makes them even more so. But when CEOs have a sound rationale for pursuing a megadeal, plan effectively for a successful integration, recognize the importance of culture in these efforts, and keep the momentum going even after the deal closes, it can indeed deliver mega returns.