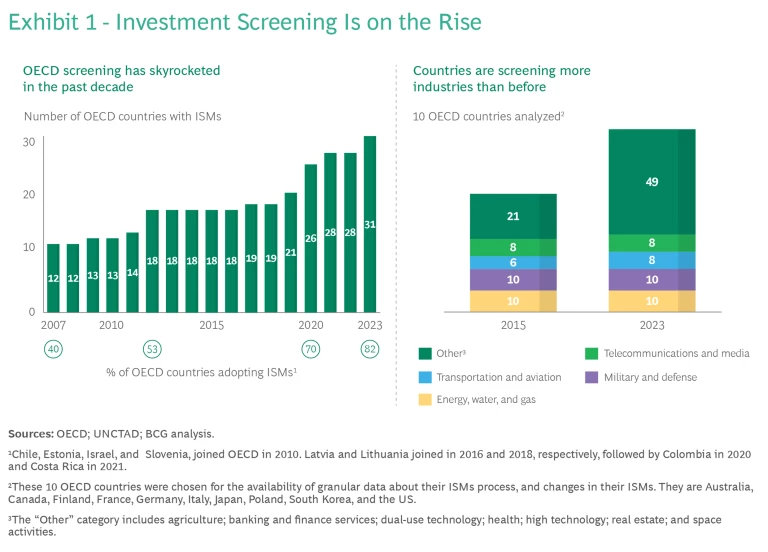

Driven by concerns about national security and foreign control over strategic businesses, countries are increasingly screening proposed foreign direct investments (FDI). Governments use these tools to ban, curb, shape, or unwind investments in targeted industries from individuals, companies, or countries of concern. Among OECD countries, the use of inbound investment-screening mechanisms (ISMs) has doubled over the past decade. (See Exhibit 1).

The So What

As geopolitical tensions and protectionism rise, companies need to prepare for this expanding use of investment screening mechanisms. For example, the UK National Security and Investment Act, which came into effect in 2022, has significantly widened the circumstances under which inbound investments are subject to screening.

Four developments explain the rise of inbound ISMs:

- Geopolitical Decoupling. With foreign direct investments now representing 40% of global GDP, a sharp rise, nations want to reduce their dependence on rivals in critical sectors.

- Technology Tipping Points. Countries want to maintain advantage over emerging technologies, such as the US currently has in advanced semiconductors.

- COVID-19. As the pandemic unfolded, nations wanted to avoid strategic companies from selling to a foreign owner at wholesale prices. They also began to screen out investments that might weaken critical supply chains such as for vaccines or pharmaceuticals.

- Rising Protectionism. Protectionist tendencies have expanded beyond global trade into foreign direct investments.

Dive Deeper

Investment screening reshapes rather displaces foreign direct investments. Foreign direct investments fluctuate with economic growth, business opportunities, and commodity prices more than investment screening. In interviews, investors said that they view the existence of ISMs as one of many signals that they evaluate in making country allocations. They also told us that they have rarely changed their allocation strategies based on new ISMs.

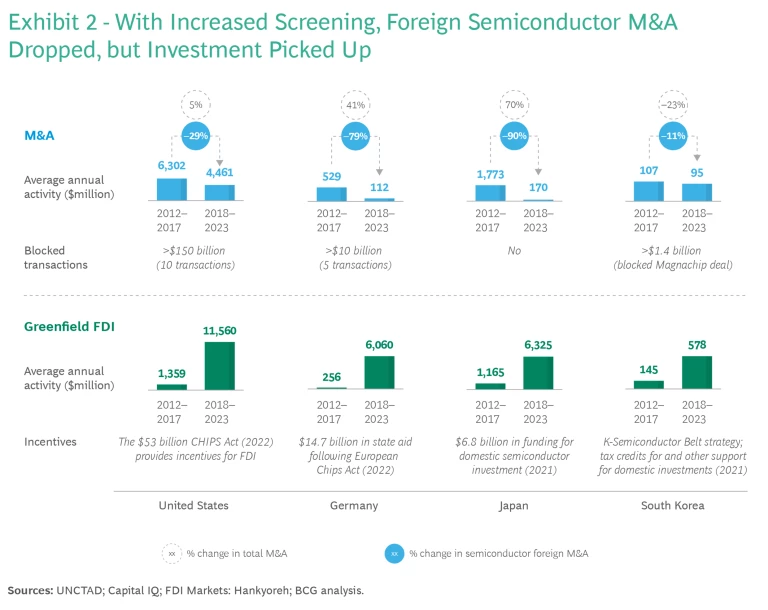

The growth of ISMs, however, has changed the mix of foreign direct investments. M&A—which is often used as a fast way to access technology, data, and know-how—has tended to decrease, while greenfield investments have risen. For example, in Germany, Japan, and the US, M&A in the semiconductor industry fell after the imposition of inbound ISMs but greenfield foreign direct investments have increased. Industrial policy, such as the CHIPS and Science Act in the US, is likely contributing to this shift. (See Exhibit 2.)

Inbound ISMs have also changed the mix of investors in favor of economic and political allies. Foreign direct investments increased among allies such as Germany, Japan, the UK, and the US after the imposition of inbound ISMs, while inbound investments from political rivals sharply declined. Germany’s share of US foreign direct investments has risen from 3% to 13% between 2016 and 2012, while China’s share has fallen to almost 0% from 4%.

What Else

Traditionally, countries have focused on screening inbound investments. But in August, US President Joe Biden signed an executive order aimed at outbound investing in advanced computing chips, microelectronics, quantum technologies, and artificial intelligence. The order is so far aimed at China but more broadly raising the visibility of both inbound and outbound screening.

Now What

This evolving world of investment screening presents challenges both for governments and investors alike.

A Playbook for Policymakers. Governments should align foreign investments with national priorities without unduly frustrating investors with lengthy bureaucratic reviews that sour the investment climate.

- Ensure due process. Countries should create impartial and timely screening criteria, so investors understand how long the decision will take and have confidence in the outcome. They should also allow investors to challenge decisions that appear to be unreasonable. This is especially true for low- and middle-income countries with less established regulatory and legal regimes.

- Reduce uncertainty. Governments should clearly define sectors to be screened; the objectives such as national security and protection of strategic assets; and the profiles of investors and the risk criteria against which investments are evaluated. They should clearly specify policy objectives, such as protection of national security, so that investors can plan an investment strategy for the country.

A Playbook for Investors. Investors in foreign direct investments tend to be sophisticated and accustomed to dealing with regulation and oversight. Many have relied on the following practices to manage the screening of their potential investments.

- Monitor. Investors have “boots on the ground,” local partners and advisors who have a nuanced understanding of the geopolitical motivations that goes beyond the dry language of the screening mechanism.

- Mitigate. Investors will change the deal structure—or arrange it through an entity located in a different jurisdiction—to make a specific deal work or target similar investments in the same value chain to hit an allocation target.

Of course, if the number and range of screening mechanisms continues to grow, old measures may not work against rules that are changing.