Although slow to start, climate action in Australia is accelerating. Major corporations, consumers, governments and regulators are looking for ways to address climate change, with financial institutions playing a critical role. By facilitating the flow of capital and capabilities to the right opportunities, not only can banks and insurers lower their risk, they can also position themselves to take share of a growing green value pool as the transition gains momentum.

Due to Australia’s dependence on coal and natural gas for energy, and our reliance on hard-to-abate export industries, Australia journey towards climate neutrality has been slower, relative to other parts of the world. But now, our transition is accelerating and there are promising commercial opportunities for financial institutions, specifically banks and insurers.

The market for sustainable banking alone is expected to grow to $4-8 billion

In recent years, Australian banks and insurers have taken meaningful climate action by outlining detailed emissions reduction pathways. These pathways are designed to align their portfolios towards net zero by 2050, supported by crucial medium-term targets for 2030 and underpinned by concrete business actions. Additionally, they are creating access to capital to fund community resilience and adaptation while improving transparency by delivering on stringent reporting obligations. The question for business leaders now is ‘how can I position my business to win in an accelerating climate neutral environment?’

We propose leaders consider three levers to strategically position their businesses for long-term success:

- An operating model that supports the climate transition

- An activated frontline and organisation with climate-ready tools and knowledge

- The right product selection, market positioning and capabilities for viable economic returns

1. An operating model that supports the climate transition

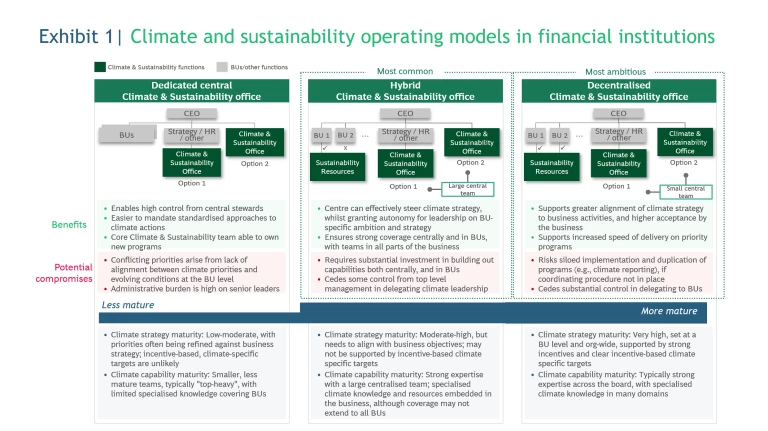

To deliver a cohesive climate strategy at scale, organisations must balance having central oversight, against empowering their teams to own and drive the agenda. The precise operating model that strikes this balance will typically depend on four factors: i) business (and climate) strategy, ii) climate capability, iii) climate-aligned culture, and iv) climate-related incentives.

For many banks and insurers, it’s unclear how climate action will specifically affect their business strategy, including which climate capabilities they will need to develop or acquire, and when. But we do know that even the most sophisticated players are still fine-tuning their climate and sustainability operating model (Exhibit 1). Many are opting for a ‘hybrid’ model that optimises for central coordination of climate efforts while enabling autonomy over delivery and outcomes across business lines, as they work towards a ‘decentralised’ model to truly embed climate in the way they do business.

Exhibit 1. Climate and sustainability operating models in financial institutions

In our work supporting industry leaders to transform their operating models to better embed climate and sustainability, four design principles have underpinned success:

- Executive-led and business-owned| Champion your organisation’s ambition and climate strategy from the top, fostering a strong sense of ownership and accountability for execution within lines of business

- Purpose-led| Articulate your organisation’s purpose, and how it fits with sustainability, and create the environment and context to shape behaviours and make sustained change possible

- Impact-oriented| Establish quantitative measures of success to create a sense of individual (e.g. for leaders) and collective (e.g. for teams) ownership for achieving your climate ambition

- Partner-enabled| Develop partnerships that can accelerate your organisation’s capability building and learning (e.g. with government, software and data providers, peers, industry leaders)

To apply these design principles effectively, banks and insurers must ensure accurate carbon accounting for their scope 1, scope 2 and scope 3 (financed emissions). This is a critical yet challenging step in executing climate strategy: a recent BCG survey found that the biggest challenge for banks in implementing their ESG strategies is collecting ESG data (including emissions data) and implementation into their processes and systems

The right operating model can unlock significant benefits. In 2021, British multinational insurer Aviva set the industry’s most ambitious climate goal: achieving net zero across its operations, investments and underwriting portfolios by 2040. To execute its climate strategy, Aviva developed a Climate Transition Plan (CTP) with levers to reduce absolute emissions. The CTP was underpinned by a detailed operating model redesign, which fostered strong internal momentum and rallied 60+ leaders around climate goals. The company is now well positioned to expand its capabilities for risk selection and pricing of green assets, with the opportunity to grow its market share.

2. An activated frontline with climate-ready tools and knowledge

Australian businesses and consumers strongly believe that their behaviour can have a direct impact on climate change – and they’re eager to act on it:

- 75% of Australian SMEs are worried about effects of climate change on operations

4 4 SME Climate Hub Survey (N=344 SMEs across 40 countries, including Australia), Capterra SME survey (N= 255 Australian SMEs), (2023) - 50% of Australian business leaders believe that how they address environmental issues will materially inform the future success of their business

5 5 SAP Environmental Sustainability Study (2022). - 60% of Australian SMEs rate a skills and knowledge gaps as top reasons preventing action

4 4 SME Climate Hub Survey (N=344 SMEs across 40 countries, including Australia), Capterra SME survey (N= 255 Australian SMEs), (2023) - 75% of Australian consumers believe their behaviour has a direct impact on climate change

6 6 BCG Rebex Consumer Survey (2023). - 50% of Australians believe they can personally make a difference to climate change impacts

7 7 Ipsos Climate Change Report (2023). - 40% of Australians would do more if they knew others were doing the same

7 7 Ipsos Climate Change Report (2023).

So, what role can financial institutions play? Financial institutions are among the most trusted organisations in Australia

This means empowering your client-facing teams with the tools and knowledge to engage large, mid-market and SME clients on their climate strategies and carbon emissions. For example, when a major US bank implemented a climate frontline activation program across its business, bankers engaged 65% of their clients in climate strategy discussions in just 8 months. Following subsequent targeted outreach, 20% of their clients entered the pipeline or active deal conversations on climate related transactions.

In our experience, the following five steps can help financial institutions create and maintain an activated frontline and organisation:

- Baseline | Understand your starting point (e.g. survey your frontline to understand their climate knowledge, identify gaps in knowledge, data or tools and uncover where they see the greatest opportunities to meet client needs and expectations)

- Set your ambition | Align on what you want to achieve and how you will measure success (e.g. additional leads generated, revenues, engagement, customer sentiment scores)

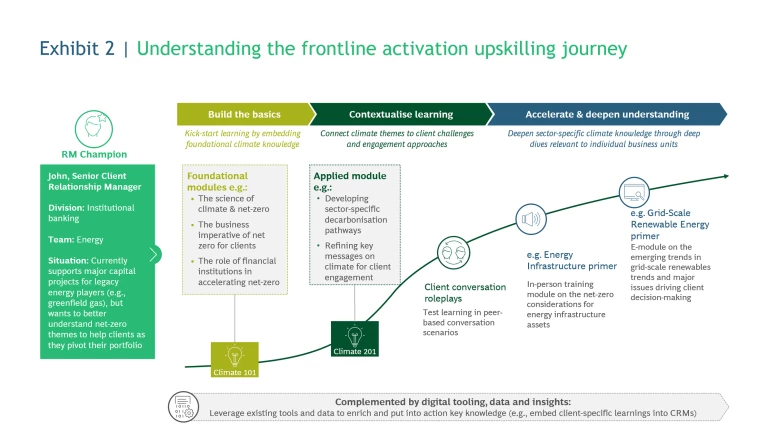

- Upskill your frontline | Develop and roll-out a bespoke climate-knowledge upskilling program (Exhibit 2), informed by the needs of your frontline, relevant data gaps, and the most pressing climate topics for clients, enabled by familiar and effective digital tooling (e.g. CRM)

- Test and learn | Gather feedback from clients and the frontline and monitor progress against your measures of success to inform modifications to the program before scaling

- Scale | The frontline is only the beginning – extend this capability by activating the broader organisation to create a ‘second line’ (e.g. Risk, Finance, HR), to drive your climate ambition and strategy

Exhibit 2. Understanding the frontline activation upskilling journey

3. The right product selection, market positioning and capabilities for viable economic returns

While globally, sustainable financial products are among the most impactful tools for driving decarbonisation, Australia has been slow to develop and adopt these products

When choosing the products to offer, there are three important questions for business leaders to consider:

- What product offering addresses our clients’ needs, and presents them with what they need to participate in the climate transition?

- How should our organisation position itself in the market to achieve economically viable returns?

- What capabilities do we need to build to effectively compete in this space?

Let’s explore how to answer these questions with a wholesale banking example.

Products

Banks channel capital into green finance primarily through capital market activities such as bank-facilitated green bonds; lending activities such as green projects and sustainability-linked loans (SLLs); own loan capacity expansion such as bank-issued green bonds; and equity stakes such as green ventures

While the long-term opportunity for such sustainable products is clear, achieving short- to medium-term profitability can be challenging. For example:

- Green bonds offer only marginal benefits to issuers, while incurring extra costs due to reporting and compliance obligations. Studies indicate no consistent pricing advantage for ESG bonds

11 11 https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-10/ESMA50-524821-2938_The_European_sustainable_debt_market_-_do_issuers_benefit_from_an_ESG_pricing_effect_0.pdf . - Green loans face intense competition driving down pricing/margins, with banks eager to add these products to grow and meet climate commitments. Corporate borrowers taking out green loans, expect to pay lower interest rates than those with brown loans, due to environmental benefits. For example, to attract new clients, major Australian banks have recently launched Business Green Loans, offering lower rates for sustainable loans designed to fund ambitious energy efficient initiatives, even though their cost structure is the same or higher

12 12 https://www.anz.co.nz/business/borrow/anz-business-green-loan/; www.commbank.com.au/articles/newsroom/2024/03/CBA-launches-business-green-loan.html; https://www.westpac.co.nz/business/products-services/loans-overdrafts/sustainable-business-loan/; https://www.nab.com.au/business/loans-and-finance/vehicle-or-equipment/green-equipment-finance, https://www.nab.com.au/business/loans-and-finance/agribusiness-loans/green-finance-agri, https://www.nab.com.au/business/loans-and-finance/business-loans/commercial-real-estate) (non-exhaustive list). . - Project finance must balance higher returns with higher, hard-to-control risks. Many technologies, such as green hydrogen and geothermal power plants, are in early development and adoption stages, affecting risk/return profiles due to high capital commitments, discounting effects and market, tech and regulatory uncertainties. Mitigation strategies depend on costly due diligence and public sector cooperation to de-risk policies

13 13 https://www.wri.org/insights/de-risking-low-carbon-investments .

Market positioning

Viable economic returns don’t lie primarily in the product itself, but in scaling volumes and capabilities, and cost-efficient operating models. It is important to know where to play and how to position your business for success.

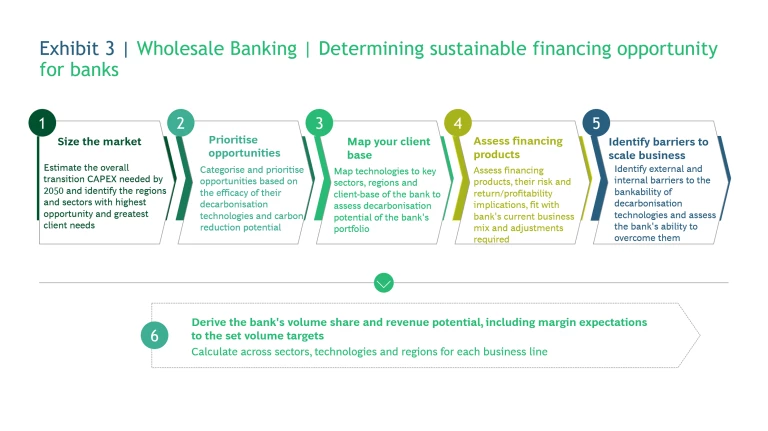

The most effective approach to identifying attractive climate-related financing opportunities involves sizing the market and understanding the addressable opportunity, through six steps (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3. Wholesale Banking | Determining sustainable financing opportunity for banks

Capabilities

In addition to selecting the right products and market positioning, improving profitability requires financial institutions to selectively build emergent climate and technical capabilities based on a structured business case. This includes building asset-specific expertise in regulation — including green taxonomy — and the technology related to the underlying assets being financed, such as bespoke renewable energy technologies. Additionally, cross-functional skills in CO2 accounting, data analytics, risk management, and supporting functions are essential. These capabilities ensure proper emissions tracking, climate disclosure reporting and compliance as well as pricing and underwriting related to the underlying assets. This is particularly important as a defensive play in a market like Australia, where government policies — including regulatory changes — technological innovation, and greater consumer awareness, demand and willingness to pay for sustainability will likely make sustainable products increasingly attractive in the future.

Summary

Financial institutions, particularly banks and insurers, support sustainability efforts across all economic sectors, and from major corporations to the individual customer. By creating greater access to green-capital, financial institutions can meaningfully gain additional value in rapidly growing asset classes.

The authors extend their gratitude to Erich Suess, Natalie Ernst, Marko Kraljev, Arjun Nath, William Ta, Benedicte Montgomery, Mihirkul Vikram, Zoe Whitewolfe, Raluca Gligor, Jan Loubal, Ashlen Wood, Julie Nguyen, James Meland, Rebecca Diepenheim and Krishna Das for their vital contributions to this article’s development.