The evolution of global sourcing has been shaped by China’s significant role as a supply powerhouse, yielding impressive procurement efficiencies and cost savings. Now, however, in the face of shifting strategic landscapes, decision makers across industries are scrutinizing the long-term viability and risk profile of their sourcing strategies.

This reevaluation has been spurred by factors both within and outside of China’s borders. Domestically, China’s economic progress has led to rising costs, including labor costs, while increased competition and protective trade policies have altered the market’s dynamics. Internationally, geopolitical tensions, stringent regulations (such as the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act), and the potential for global disruptions (resulting from a pandemic, for instance) have propelled global sourcing strategies to the top of corporate agendas.

In response, companies are seeking to develop strategies that preserve commercial benefits while offering resilience. Balancing the challenges and objectives requires a two-step approach. Companies should start by evaluating each product category with respect to the need for and the ease of changing the sourcing strategy. They can then apply the results of this category baselining to define the optimal strategy. To guide the effort, we have developed a framework that sets out a range of strategic sourcing configurations.

Category Baselining: How Necessary and Easy Is Change?

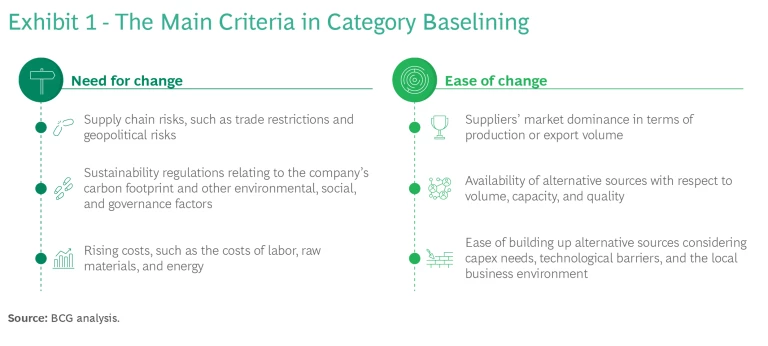

Drawing broad conclusions about global sourcing can be difficult and risky because every product category has a distinctive market dynamic, competitive landscape, and value chain. The category baselining allows companies to consider these nuances. (See Exhibit 1.)

Need for Change. The need for change is a function of supply chain risks, sustainability regulations, and costs.

Supply chain risk continues to be a dominant factor in global sourcing strategies and is thus the primary consideration when gauging the need for change. The need is stronger in those categories whose supply chains are most vulnerable to trade restrictions or other geopolitical developments. Products such as semiconductors, which require intellectual property protection and unique local content specifications, may also be under pressure.

The rise of sustainability regulations is propelling the reshoring and near-shoring of supply chains. Heightened public awareness and government focus on environmental, social, and governance factors, such as a product’s carbon footprint, are driving these changes. Sustainability regulations not only amplify compliance risks but also drive higher purchasing costs. An example is the carbon border tax currently under review by the European Commission.

Companies need to gauge how expenses associated with the primary costs of purchased goods are affecting the manufacturing advantages offered by China. Although labor costs have steadily risen over the past decades, production companies in China continue to benefit from favorable raw-material and energy costs.

Ease of Change. The ease of change is a function of market dominance, the availability of alternative sources, and the feasibility of building up those sources.

Market dominance is the most pivotal factor in determining the ease of change. In certain categories, China has cemented its leadership in both production and exports; for example, Chinese-produced crude steel accounted for 52.9% of global output in 2021, and its share of metal casting reached 48.9% in

Assessing the availability of alternative sources involves more than just volume considerations. The quality standards those sources can maintain, along with their ability to absorb redirected volume from China, are fundamental factors in the ease of transition. Beyond cost benefits, China has remained a preferred option for global sourcing owing to its robust infrastructure and well-established industry clusters throughout the value chain.

Companies need to evaluate the feasibility of building up alternative sources, considering the required capital expenditure, potential technological barriers, and the local business environment, among other factors. It is important not to underestimate the time required to develop these sources. The advantages of sourcing from China cannot be readily duplicated in only a few weeks or even months.

The Baselining Matrix

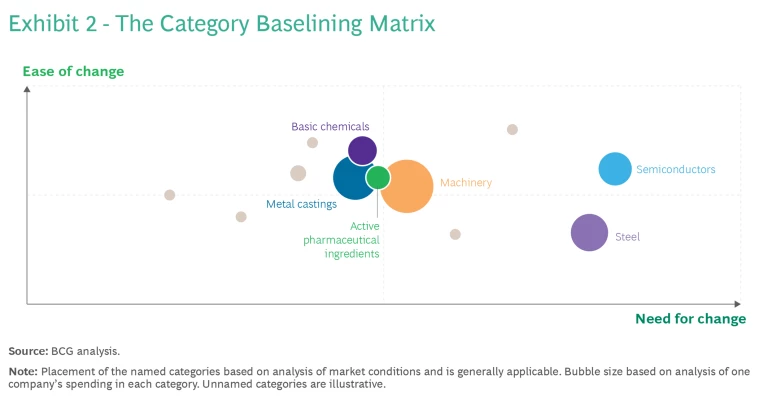

After evaluating these factors, companies can position each product category within a matrix that, by illustrating its need for and ease of change, offers guidance on refining the sourcing strategy.

For categories on the left side of the matrix shown in Exhibit 2, there is less urgency to reevaluate sourcing given the low impetus for change. However, these categories should be monitored, because shifting market conditions could increase the need for change, moving them to the right side of the matrix.

Categories in the upper-right quadrant face a strong need for change coupled with a high degree of ease of change. For these categories, it is advisable to revise the sourcing strategy. However, this process is multifaceted and must consider additional factors, such as the end product’s life cycle and the internal costs associated with sourcing modifications.

Categories in the lower-right quadrant are the most complex to address. Despite a strong need to adjust their global sourcing strategy, executing these changes will be challenging. Companies usually employ a nuanced strategy that balances risk mitigation and operational stability.

Strategy Definition: What’s the Best Approach to Global Sourcing?

In making sourcing decisions for the categories in the lower-right quadrant of the matrix, chief procurement officers must conduct a complex assessment that weighs cost, speed, and resilience. This challenge is compounded by the need to adhere to detailed requirements for technology, materials, and qualifications.

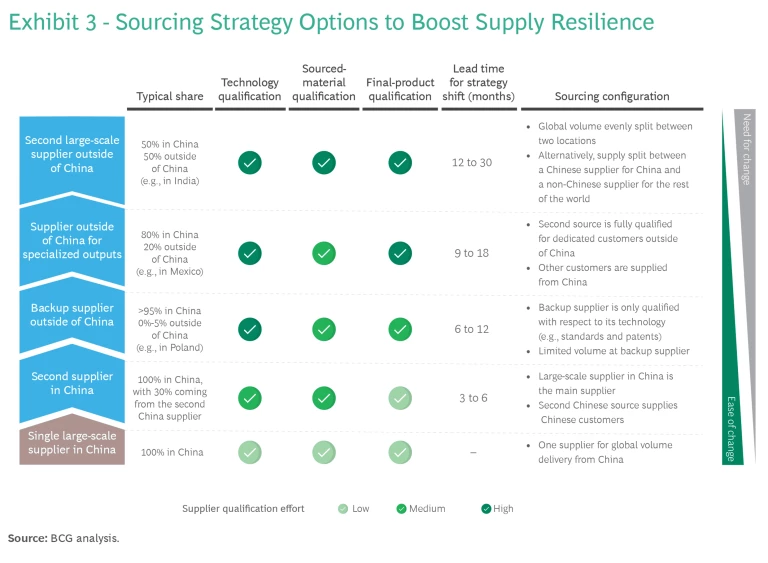

To help companies address this complexity, we have developed a framework that sets out a range of strategic sourcing configurations. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies can use the framework to guide decisions on potential sourcing scenarios, considering the need for change and the benefits of gaining flexibility within each category.

The framework considers five sourcing configurations: the conventional reliance on a single large-scale supplier in China and four strategic alternatives. Each alternative is distinctive with respect to complexity, risk mitigation, and the timeline for setting up an auxiliary source in conjunction with the large-scale Chinese supplier. Owing to the intricacies of supplier onboarding, logistical planning, and capacity augmentation, the alternative approaches may entail long activation timelines.

Importantly, these configurations are not mutually exclusive and can be combined to form a composite sourcing strategy that aligns with an organization’s need for operational resilience, market positioning, and risk appetite. Besides the use of a single large-scale supplier in China, options include a second supplier in China, a backup supplier outside of China, a supplier outside of China for specialized outputs, and a second large-scale supplier outside of China.

Second Supplier in China. This strategy enhances the supply chain’s robustness by introducing an additional source within China. The second supplier serves as a hedge, potentially easing logistics with minimal need for additional qualification by end customers. The approach is suitable for conventional products for which the risk profile justifies a diversified sourcing strategy within China. For example, a South Korean semiconductor equipment manufacturer has engaged both a primary and a backup supplier in China to mitigate risk during its growth phase. The three-to-six-month lead time for activating a second source is the shortest among the alternative strategies.

Backup Supplier Outside of China. Companies can establish a backup site outside of China to be used when the primary supply line is interrupted. For example, a South Korean producer of electric-vehicle batteries could source mainly from China but maintain a standby production facility in another country, such as Romania, to ensure continuity in case of regional disruptions. This approach is a prudent safeguard and a key element of a long-term sourcing strategy that includes the integration of non-Chinese suppliers. The 6-to-12-month activation time reflects the need for more planning and qualification than is often required for a second source within China.

Supplier Outside of China for Specialized Outputs. This configuration utilizes a supplier outside of China with expertise in specific products or components. It enhances agility and customization to serve niche markets or comply with strict local regulations. A global automotive tier-one supplier, for example, may source air conditioning systems from China for worldwide distribution, while partnering with a specialized Mexican facility to make products destined for the North American market. The strategy requires the rigorous qualification of both Chinese and international suppliers to meet distinct technological and regulatory standards. This results in an extended activation lead time ranging from 9 to 18 months.

Second Large-Scale Supplier Outside of China. Companies can partner with a major supplier outside of China that is prepared for large-scale production. (See “Apple’s Strategic Sourcing Pivot to India.”) This option is particularly suited to high-volume products that are sensitive to geopolitical risks and require a regionally diversified supply chain. Implementation requires a comprehensive qualification process across multiple facilities to ensure that suppliers can be changed without disruption. The lead time for this strategy, ranging from 12 to 30 months, is the longest among the options.

Apple’s Strategic Sourcing Pivot to India

The pivot to India goes beyond simple geographic expansion. It represents a thoughtful realignment of sourcing to support Apple’s broader business objectives. By establishing a significant presence, Apple is not only seeking cost advantages but is also bolstering its efforts to respond to market changes, gain access to India’s vast market, and navigate the intricacies of global geopolitics.

From Concept to Action

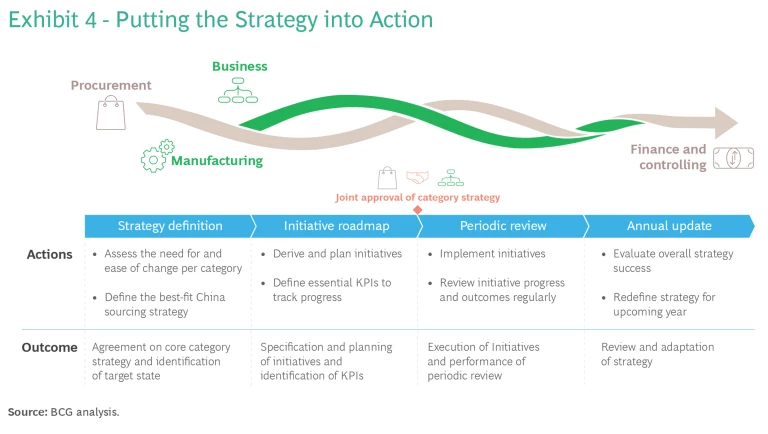

Companies must take several steps to define a global sourcing strategy, translate it into a concrete action plan, and ensure proper implementation. (See Exhibit 4.)

To lay the groundwork, companies should take a variety of actions:

- Decide whether to source locally or to utilize China's manufacturing strengths.

- Proactively cultivate a diverse network of suppliers across various regions to enable the adaptability and balance offered by the various strategic sourcing configurations.

- Implement comprehensive screening and validation processes in the selected countries.

- Strengthen existing partnerships and establish new ones to enhance resilience and minimize risks.

- Prepare to employ a combination of currently available suppliers alongside those developed for the long term to ensure immediate support as well as sustained adaptability.

After selecting a strategy, companies should define concrete implementation initiatives and prioritize them in a roadmap that sets out their sequence and interdependence. They should also define owners and responsibilities to ensure accountability.

Joint approval of the strategy by procurement and related business stakeholders is a key factor in securing the commitment of all involved functions and teams during implementation. Equally important is establishing a committee that regularly reviews progress, makes the necessary decisions, and resolves conflicts or escalates when necessary. Finally, companies should evaluate the strategy annually and redefine it as needed for the upcoming year, bearing in mind the lead times for making adjustments.

In taking these steps to revitalize their global sourcing strategy, companies should follow three main imperatives:

- Proceed with caution. Global sourcing can offer significant value for procurement, but do not overlook the associated risks.

- Strike a balance. Assess the need for and ease of change for each category and their implications for the sourcing strategy.

- Integrate into governance. Regularly review the sourcing status for all categories and adjust the corresponding strategies to keep pace with the ever-changing supply market.

Mastering the complexity of global sourcing is crucial for companies seeking to maintain resilience and a competitive edge. The transition from tried-and-true approaches to alternative sourcing options is imperative, even as China continues to play a major role in many sourcing strategies. Executing this strategic pivot requires a blend of analytical acumen and bold decision making. Companies that succeed in building more diverse and robust supply chains can secure a path to sustainable growth, despite the uncertainties of shifting consumer trends and ongoing geopolitical challenges.