This article is part of a series examining the competitive outlook for key global process industries and how they can prosper in an uncertain future.

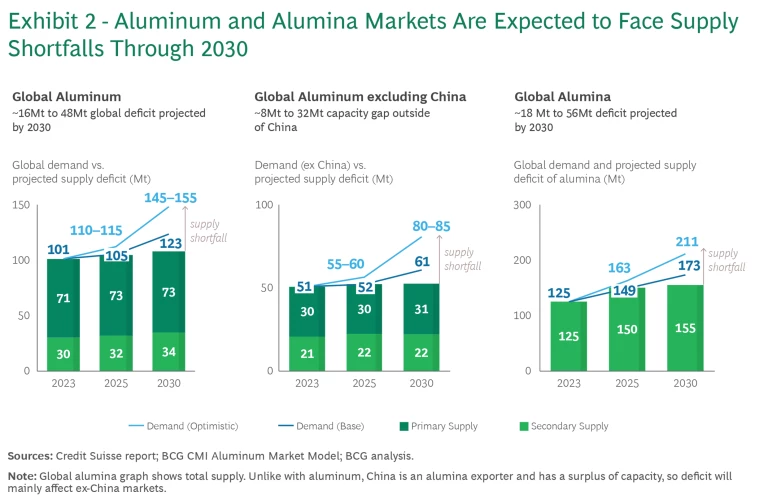

For aluminum producers, a looming supply problem is the biggest challenge of this decade. Even if demand were to increase at a modest pace, the global shortage in aluminum could amount to over 16 million metric tons by 2030—based on conservative projections. The shortfall threatens to push up prices and make aluminum far less competitive against alternative metals such as copper and steel.

Until recently, China supplied much of the word’s aluminum, keeping demand and supply largely in balance. But the market environment is in flux. The Chinese government has imposed an annual cap of 45 million metric tons on aluminum production, both to curb pollution and improve asset utilization. Policymakers want the country’s aluminum output used to manufacture value-added export items, such as cars and refrigerators, rather than exporting the metal as a commodity product. In the meantime, sources of growing global demand, such as emerging markets and green energy applications, are rapidly emerging.

What can the aluminum industry do to fix the supply problem before it worsens? Building extra capacity is one answer. But the industry is strapped for cash, and adding capacity is made more difficult due to high capex costs and high borrowing costs. We estimate that the cost to the industry of building sufficient extra capacity could be between $60 billion and $90 billion. Aluminum smelting is also energy-intensive, and players need to ensure they build new plants in locations with access to reliable, inexpensive—and preferably clean—energy. Talent issues in process industries and the high total cost of ownership of aluminum assets add further complexity.

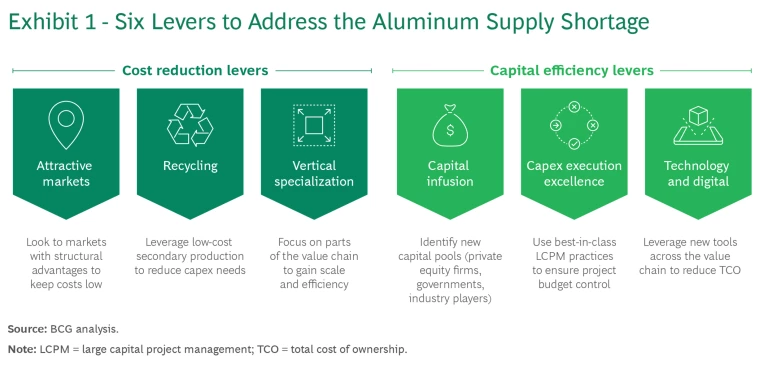

Faced with these huge challenges, we believe the industry must consider more radical action steps to achieve future success. (See “The Future of Process Industries.”) These fall into two broad categories: The first involves cost reduction levers, while the second involves raising capital and deploying it more effectively. In this article, we explore six actions across both categories that can help aluminum players navigate the industry’s supply shortage. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Future of Process Industries

Each article in the series will examine the nature of the new business reality faced by a particular process industry, and how the coming changes will drive technological progress, redefine the industry’s cost structure, and reshape its competitive landscape. The goal: to provide industry leaders with the data and guidance needed to ensure their companies can thrive in the coming years.

Demand Will Be Supported by New Growth Drivers

Over the past two decades, global aluminum demand has risen by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of close to 5%. This increase has been driven by China, which has seen consumption increase ten-fold since the early 2000s, and by strong worldwide growth in transportation and construction. However, Europe’s slowing economy is now hurting demand in the region, while a deceleration in China’s property sector is set to reduce the country’s CAGR in aluminum from 12% to just 3%.

Yet these declines will be countered by several tailwinds. Demand growth will likely be range-bound between 3% and 4% from now through 2030 as a result of growing consumption in emerging markets, aluminum’s role as a substitute for other metals, and the global transition to green energy.

We expect India to be among the fastest-growing aluminum markets worldwide—with demand growth rising by a CAGR of close to 6% from now until the end of the decade—driven by consumption in the infrastructure, construction, and automotive sectors. Aluminum demand in developing economies in Africa and Latin America could follow a similar path.

Demand could also be buoyed by the use of aluminum as a less expensive and more readily available substitute for other materials facing supply problems, such as copper and carbon fiber. We estimate that around 10 million metric tons of aluminum would be needed by 2030 to replace copper in internal wiring, overhead transmission lines, and underground electricity cables. In addition, the energy transition could require an additional 20 to 25 million metric tons of aluminum by decade-end for the solar and wind farms and battery storage needed to achieve net zero.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on industrial goods

Supply Challenges Persist

Despite the growing demand, the outlook for aluminum supply is not so reassuring. Deterred by the threat of cost-effective Chinese imports, aluminum companies outside China have only added about 3.5 million metric tons of new capacity over the past 10 years. This has increased production capacity (excluding China) by 12%, an annual growth of just around 1%.

Even if demand were to grow at a base-case scenario of 3% CAGR, our conservative estimate of the supply shortfall in 2030 would be around 18 million metric tons for alumina and 16 million metric tons for aluminum (half of which comes from outside China). (See Exhibit 2.) The expense of building sufficient production capacity to plug this aluminum supply gap would still be huge. Higher environmental standards and labor costs are driving rapid increases in capex costs for an aluminum smelter. We estimate that the bill to the industry would be between $60 billion and $90 billion.

New Approaches Are Needed

Securing the resources to substantially increase capacity would be a stretch for the industry. Aluminum companies have significantly more debt on their balance sheets than other metals players. In 2023, for example, debt made up 52% on average of the enterprise value of the top 10 global aluminum companies. By comparison, debt accounted for 43% of the enterprise value of the top 10 steel players and 39% of the top 10 copper players. Given their already indebted position in a macroeconomic environment marked by high interest rates, taking on additional debt to finance large capacity additions such as new smelting facilities could negatively impact aluminum companies’ credit ratings, interest costs, and share prices.

However, we believe a bolder approach is required for the industry to meet future demand. Aluminum companies can benefit from six actions that have the potential to transform aluminum economics, enable companies to use scarce capital more efficiently, and help them tap new financial sources.

Focus on attractive markets.

Adding production capacity in fast-growing markets that offer low-cost energy and alumina, reliable clean energy, and political stability can reduce players’ cost base, ensure proximity to centers of strong demand, and secure better access to regions, like Europe, that are introducing taxes on imports with a high carbon content. Energy and delivered alumina each make up around 30% to 40% of the total cost of aluminum smelting. Consequently, regional differences in the price of these inputs can have a big impact on companies’ competitiveness.

The US, Brazil, the Middle East, and India stand out as attractive regions for investment. For instance, the US has an abundance of scrap and can become a major hub for secondary (recycled) aluminum production. Brazil, meanwhile, has substantial hydropower generation, which can be used to make green aluminum, as well as access to substantial alumina capacity that keeps delivery costs low. In the Middle East, governments have been investing heavily in green energy for large capital projects that ensure a steady supply of clean power. Oman, for example, is building a steel plant that will use green hydrogen and could serve as a blueprint for green aluminum production. India has relatively low setup and operating costs for facilities; however, it does not yet have sufficient clean energy access to produce green aluminum at scale.

Increase recycling capacity.

Aluminum is ideal for recycling because it can be almost infinitely remelted without losing its original properties. Recycling allows aluminum companies to be part of the circular economy. And because the capex cost of setting up remelting facilities for aluminum are about one-third of similar smelting setup costs, recycling offers the industry as a whole the chance to shift the cost curve downwards. (Of course, primary aluminum will still be required for high-purity components in certain industries as well as other applications.)

While recycling partly addresses the industry’s problems, companies will have to solve the problem of limited scrap availability worldwide. They will also need to identify attractive opportunities within the scrap value chain to make setting up the infrastructure worthwhile. We’ve found that value creation differs widely depending on the activity. Scrap processing (with average gross margins of 10% to 25%) and remelting and casting (with margins of 5% to 11%) are the most attractive from a margin perspective. (See Exhibit 3.) To compete effectively in scrap processing, players will need to invest in advanced sorting technologies. In the remelting and casting segments, casting offers players higher profit margins, but remelting can provide good returns on capital employed because of the low investment requirements.

Pursue vertical specialization.

As a moonshot action, the aluminum sector can also reinvent itself through vertical specialization. By disassembling the value chain and specializing, companies can unlock capital and improve efficiencies. The activities of most aluminum companies, especially outside China, are spread broadly across the value chain. This has resulted in fragmentation and lack of scale. As a remedy, companies could specialize in discrete parts of the chain, whether that’s mining and refining or smelting. There is precedent to doing so from other industries; chemical companies have increasingly targeted specific parts of the value chain to create strategic focus and improve performance. In recent decades, for example, large chemical players have split out their petrochemical, commodity, and specialty chemical businesses. This has enabled them to specialize in one or two areas, while forming joint ventures to source raw materials where needed.

Such specialization offers several advantages. For example, aluminum players would be better able to scale production capacity to match demand, helping to mitigate the effects of high financing and capex costs and improving capital deployment. By leveraging economies of scale in materials and energy sourcing, companies can benefit from more competitive operating costs. And because their operating assets are larger, companies can use technologies more effectively and invest in technological innovations. (See Exhibit 4.) Becoming more specialized will also help aluminum players navigate the talent trap confronting process industries—the exodus of experienced employees due to retirement—as they will be able to focus on recruiting for a smaller number of activities.

One potential concern for players that choose to specialize in mining or refining of alumina is its availability. However, we’ve found that 45% of global alumina refining capacity is non-captive. In addition, alumina is found throughout the globe, and there are several worldwide trade routes that supply the material.

Seek a capital infusion.

Because aluminum companies have high levels of debt on their balance sheets, they need to tap sources of capital outside the industry for funding. There are a few areas they should look at. Private equity firms are one potential source of external funding. Government grants are also available for certain projects. In the US, for example, 48C tax credits help support the setting up of aluminum facilities, provided the facility uses clean energy to smelt metal or is a recycling facility that produces aluminum from scrap. Alternatively, they could also turn to other industrial companies in adjacent sectors. One potential opportunity could be steel, where the recent market upcycle has helped steel players garner cash. Aluminum could be a worthwhile diversification opportunity for steel mills seeking to deploy this capital by partnering with aluminum players.

Deploy capex execution excellence.

Recently, we have seen far too many companies that undertake large capital projects fall behind schedule and run over budget. Therefore, as aluminum players tackle the problem of how to source funding, it is essential that they also solve the problem of how to deploy this funding effectively. This involves multiple considerations. First, project development teams must be sized appropriately and have the right skill sets for the job. By making up-front investment in pre-FEED and value engineering, companies can ensure their capex forecasts are accurate. The right tools and processes (such as impact centers and look-ahead plans that operate over a three-week and three-month period) need to be in place so that teams can either pre-empt or identify and resolve issues. Finally, the team’s knowledge should be regularly augmented using software-based approaches such as Building Information Modeling (BIM).

Being aware of these steps, and diligently applying them, can help aluminum players side-step common pitfalls as they build out more refineries and smelters.

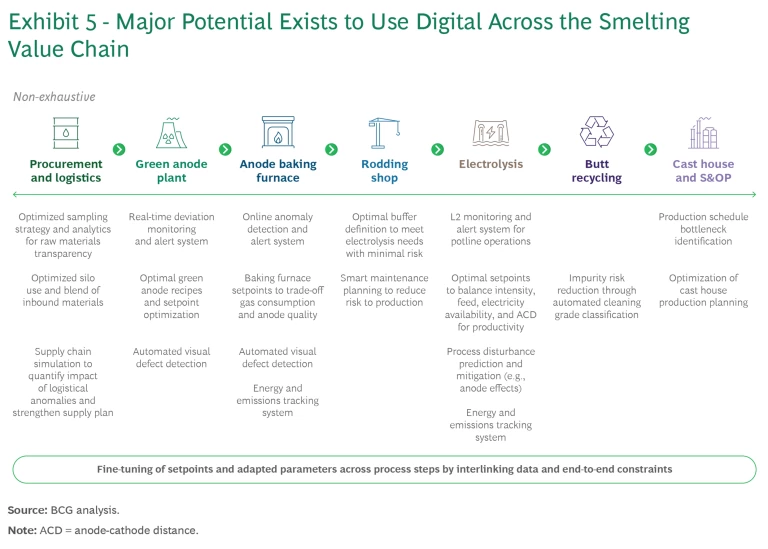

Optimize technology and digital.

Aluminum companies can tap digital tools to help manage the total cost of ownership of their facilities. Advances in technology, such as generative AI, open up opportunities for companies across the value chain. Examples include systems that monitor production lines for process deviations in real time and then alert managers, as well as automated visual defect detection systems. Within smelting, digital can deliver efficiencies and strengthen supply chains in procurement and logistics, and can track energy usage and emissions during the electrolysis process. (See Exhibit 5.) We estimate that by using these tools, companies can reduce the cost of smelted aluminum by $20 to $30 per ton, helping to free up resources to meet capacity demands.

To fully reap the substantial benefits from strong and growing demand, the aluminum industry needs to take radical action. By building new capacity in low-cost, fast-growing markets, companies can reduce their cost base and be close to demand centers. Greater specialization within the value chain can deliver both efficiencies and scale. Recycling will not only reduce companies’ capex expenses, but also help them achieve their sustainability goals. Tapping new capital pools will enable players to boost their financial firepower. Managing large capital projects more efficiently will free up resources for other priorities, while deploying digital technologies can curb overall costs and improve productivity. By taking some or all of these steps, aluminum companies can dramatically increase their chances of future success.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their BCG colleagues Varun Govindaraj and Chirag Thaker.