In the past few years, the risks of conducting business internationally have multiplied. With Brexit, the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, political uprisings in Latin America and Africa, climate change, the COVID pandemic, and continuing supply chain disruptions—to name just a few global crises—the world has become a more complicated place than at almost any other time in recent history.

The long list of geopolitical risks presents a particular set of concerns to companies that are engaged in cross-border joint ventures (JVs). Foreign partners in a JV may already be accustomed to ongoing risk from such factors as local regime change, intellectual property (IP) disputes, or economic downturns. Now, however, a new BCG study finds that the increasingly volatile geopolitical environment has many companies reconsidering where they plan to set up future partnerships and how they should protect themselves.

In July 2023, nine years after BCG first undertook an extensive analysis of the state of value creation in joint ventures , we conducted a fresh cross-sector survey of 159 business executives in companies that operate JVs across the globe. (See Appendix . )

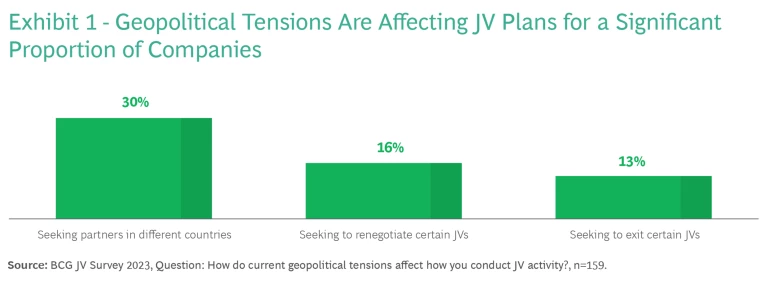

Given that close to two-thirds of new joint ventures and alliances formed between 2010 and 2022 were composed of partners from different geographies, we asked about the specific concerns of cross-border ventures. The survey found that most firms remain committed to their existing JVs even if they’re facing certain geopolitical challenges, with two-thirds saying they plan to continue operating their existing partnerships. However, a significant number (33%) are considering changes in the way they pursue JV activity due to geopolitical tensions—such as moving their JVs elsewhere, renegotiating terms, or exiting certain partnerships. (See Exhibit 1.)

Picking up and leaving a country where problems have arisen is an extreme response, and there are ways to avoid this scenario. Over time, foreign partners in many cross-border JVs have found that one of the most valuable safeguards is to build in a set of protective mechanisms that extend beyond the scope of legal contracts. For example, in a country where the laws and litigation around IP are either vague or frequently sidestepped, a foreign partner might insist on shipping fully programmed microchips into the local factory so that the local partner can’t easily reproduce the technology behind the chips. Among the executives we surveyed, 44% said they’ve found it important to institute non-legal protections, and 32% feel that these protections have become more important over the last decade.

At the top of the list of such non-legal protections is the practice of restricting the other partners’ access to IP or raw materials that are critical to the JV operations. Also important is “dual hatting,” in which the foreign partner is one of the key customers or suppliers to the venture, a practice that provides additional negotiating leverage. Foreign partners are also making sure that they establish direct relationships with other customers, suppliers, and/or government bodies as a backstop in case their relationships with their local counterparts turn sour.

Still, some are finding that either the geopolitical risks in certain cross-border deals are so high that they are looking elsewhere for future growth, or there are greater incentives to turn their sights to other markets.

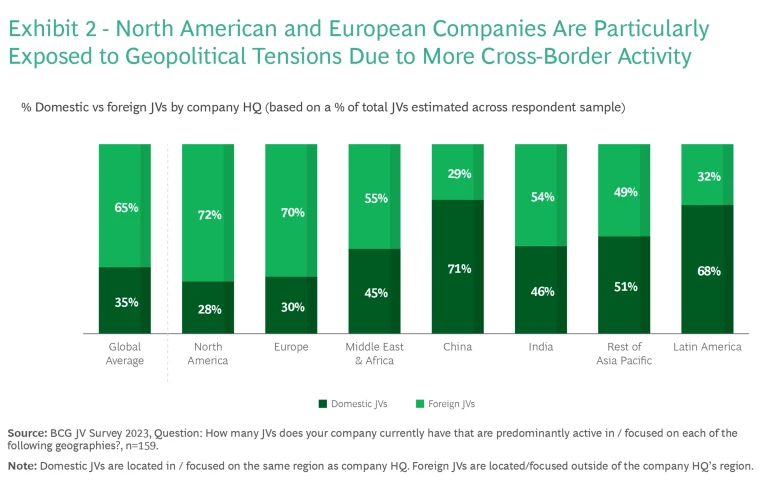

North American and European firms are likely to be more exposed to geopolitical risks, as a higher proportion of their JVs (about 70% in our sample) involve foreign partners. By comparison, cross-border ventures comprise only about 30% of all JV activity for Chinese companies, and about 50% for companies in India and the rest of the Asia Pacific (APAC) region. (See Exhibit 2.)

Moving Around the Map

We looked closely at the views of foreign companies operating JVs in China since it has been a focal point for global joint venture activity. Approximately 20% of all cross-border JVs launched over the past 13 years have included a partner headquartered in China, according to BCG research. Our survey found that around half of all non-Chinese firms with JVs in China plan to maintain a similar level of JV activity there, relative to the last decade. A large number of these companies are based in the Middle East, Latin America, India, and other APAC countries.

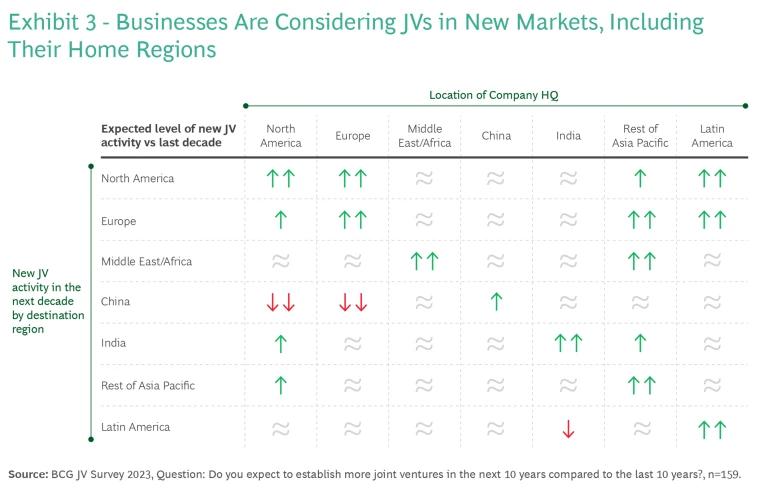

Businesses in North America and Europe, on the other hand, are looking at having fewer partnerships in China. This may reflect a number of factors beyond geopolitics; for example, China’s GDP growth is slowing now that the economic base is higher, while local companies have become more competitive in their own right. In addition, in certain industries China no longer requires foreign companies to set up JVs in order to operate there.

North American and European companies may also be looking at partnerships closer to home as a result of incentives arising from such factors as national security, green energy, and industrial policy. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, for example, imposes a levy on imports of goods produced in carbon-intensive facilities. Consequently, a European company in a JV abroad might face a choice of either decarbonizing the foreign production facility or relocating it. In the US, companies may be driven by incentives to set up domestic JVs in the CHIPS and Science Act, which encourages domestic semiconductor production, and the Inflation Reduction Act, which incentivizes renewable energy transition .

Many APAC countries outside of China and India are also planning to increase their JVs in North America, Europe, the Middle East, and their APAC region, while Latin American companies are looking at more activity in North America, Europe, and Latin America itself. (See Exhibit 3.) These plans are likely the result of both geopolitical shifts and growth opportunities.

Preparing for a Changing World

At the same time, our survey respondents are clear that they’re concerned about being prepared to execute future ambitions for new and existing JVs in a world of heightened geopolitical instability. Only 23% said they believe they are well prepared for the geopolitical scenarios that might be on the horizon, while 70% said they are only somewhat prepared and 8% said they do not feel prepared at all.

There are a number of ways that a foreign partner can build resilience into its cross-border JV agreements so that the business is better prepared for what might lie ahead. In particular, we recommend five practices to help cross-border JV partners succeed in the current international paradigm.

Stress-test your JV strategy and business cases for the impact of potential geopolitical shifts.

Conduct upfront scenario planning and simulations for different outcomes when you’re examining the viability of the venture and your capital commitments. Determine strategies for what you would do if the geopolitical environment were to change. This scenario modeling should form a critical part of a company’s decision-making on plans for existing partnerships as well as whether to proceed with a new venture.

When looking to do business in new geographies, recognize that not all cross-border JVs are the same.

Partners have to be attuned to each country’s unique social, political, legal, and accounting frameworks. Cultural contrasts in any JV deal can affect the tone and pace of negotiations, and the outcome will have a lasting impact throughout the life of the partnership.

Create a robust governance structure with non-legal protections and sufficient escalation pathways.

Traditionally, governance structures have relied on legal protection mechanisms, such as contractual voting rights and formal dispute resolution processes. It is increasingly important, however, to reinforce strong governance through the use of non-legal protection mechanisms. This is not only relevant to new JVs; non-legal protections can be strengthened in existing JVs by making the most of “dual hatting” opportunities.

Establish deep personal relationships to see through political divides.

One-to-one relationships are more important than ever at a time when JV partners need to mitigate risks in such areas as government intervention, regulatory changes, and shifts in national interest. A foreign JV partner should be prepared to develop close relationships with policy-makers, suppliers, customers, and their own local counterpart from the start, and continue these relationships as the local environment evolves.

Ensure there is a clear exit plan spelled out in the agreement.

With uncertain conditions around the world and a large number of JVs having no fixed lifetime, it has become more important to clearly define the exit mechanism for both parties upfront. Without such a plan, a foreign partner could face extreme circumstances such as war or political turmoil with no viable way out. This predicament might be the result of having no prescribed price-setting mechanism or the non-exiting party holding asymmetric veto or buy-out rights. Or, if much of the exit plan has been left up to “negotiation in good faith,” the foreign partner might find that good faith has worn thin by the time an emergency occurs. Ultimately the partner might have no choice but to remain in place, or they might have to leave value on the table in order to exit.

Companies shifting their JV activity towards more domestic partnerships should also recognize how corporate cultures can differ as much as country cultures. A shared geography might eliminate some of the concerns about political, legal, and accounting differences, but it will not guarantee harmonious corporate values and cultural compatibility. Wherever they are now—and wherever they are going—JV partners must critically evaluate their activities and consider the future risks in every location.

If a JV is structured to be robust, it can withstand most stresses, but all partners need to ensure that they’re adequately protected against unforeseen political and economic challenges. All participants will need to recognize, too, that the rule book of the past may need to be adapted to the changing world of the future.