Executive Summary

Biodiversity Credits Are Evolving, but They Remain Controversial

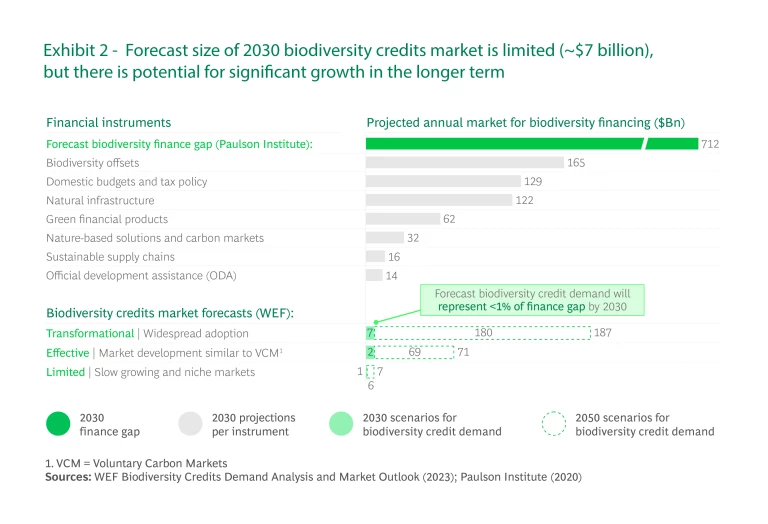

An increased supply of viable, high-integrity projects and a drastic and sustained acceleration of capital is needed to close the ~$700 billion average annual biodiversity conservation financing gap. The COP15 conference of December 2022 in Montreal, Canada, in the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF), identified biodiversity credits as an innovative mechanism that holds potential for stimulating projects and financing, and recommended that they be investigated further.

Since the GBF was adopted, there has been rapid global development of biodiversity credit markets, with over 30 biodiversity credit pilots under way. However, experts remain divided about their utility, feasibility, and effectiveness. What’s missing is a clear demand-side use case.

Who Will Buy Biodiversity Credits and Why?

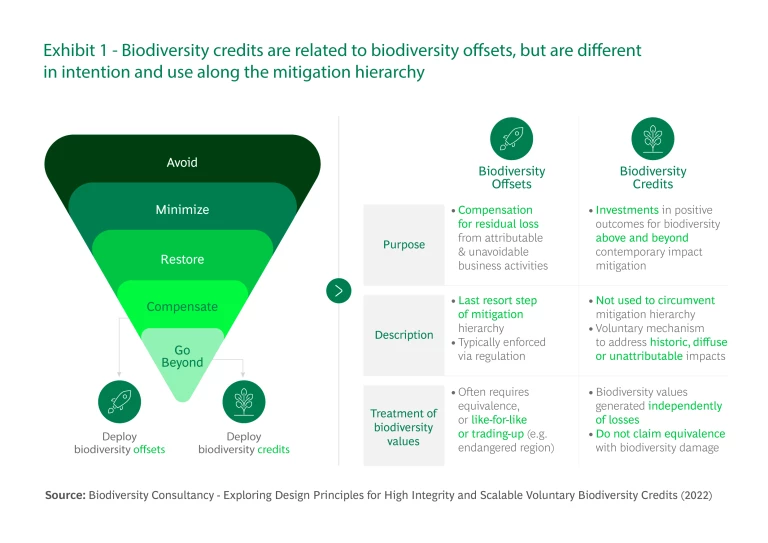

Biodiversity credits are related to biodiversity offsets, but are different in intention and use along the mitigation hierarchy. The mitigation hierarchy is a tool that guides users on how to limit potential negative impacts on biodiversity from development projects. Following this hierarchy is fundamental to achieving “no net loss” or being “nature positive.”

The steps of the mitigation hierarchy should be followed sequentially:

- Avoid negative impacts (changing site, limiting area impacted, etc.)

- Aim to minimize impacts (improved efficiency, reduced resource demand, etc.)

- Restore and regenerate habitats based on unavoidable impacts

- Take responsibility by offsetting residual impact via biodiversity offsets to ensure that there is no net loss (as a “last resort”)

Only then can additional voluntary contributions toward global nature goals be made using biodiversity credits (among others)—beyond offsetting direct impacts and dependencies (“go beyond”). Quite simply, biodiversity offsets are compensation for residual loss from attributable and unavoidable business activities, while biodiversity credits are voluntary investments in biodiversity above and beyond contemporary impact mitigation. They are intended to be bought and sold in voluntary markets, with the private sector seen as the primary buyer.

Based on the strict definition, and lack of maturity of the market today, biodiversity credits should not be used as offsets, given their non-fungibility (specific nature and an overall lack of scientific consensus on how to value and equate biodiversity) and the risks of greenwashing/undermining conservation efforts. The risk is that companies may misuse credits as a “license to degrade”—damaging one area of biodiversity by justifying “compensation” in another area with different characteristics, which could lead to a net loss in biodiversity.

Biodiversity credits are fundamentally different from carbon credits, as the latter can be used as compensation, given the fungibility of CO2e, while biodiversity credits cannot.

Buyers of Biodiversity Credits Need “Something in Return”

While demand-side use cases for biodiversity credits exist, the World Economic Forum estimates that the size of short-to-medium term demand will be limited to about $1 billion to $2 billion by 2030

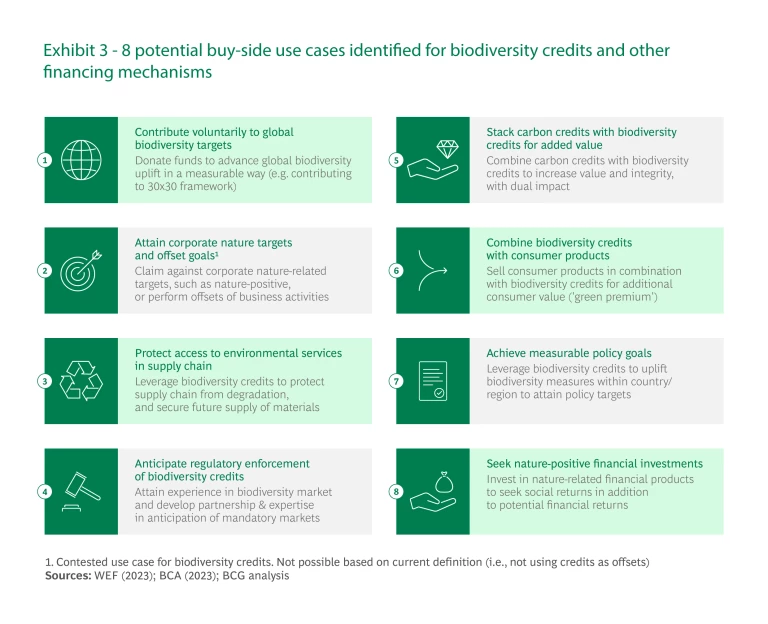

Biodiversity credits are purely voluntary. Under their current definition, they are essentially corporate conservation philanthropy. At this stage, there are no regulations or incentives to drive corporates to buy biodiversity credits at volume. Credits are more administratively complex and contain more greenwashing risks than do conventional corporate social responsibility efforts, without clear upside. Company sourcing sheds are often not located in the same geographical area as critical biodiversity credit areas and projects, inhibiting large-scale demand from the supply chain angle.

A direct project-based approach seems more logical for corporates to follow, focusing on developing a nature-resilient supply chain by setting up and partnering directly with conservation/restoration project developers, who often have robust monitoring and evaluation. Here, corporates have more control, with direct impacts against their footprint.

Demand for biodiversity credits could increase if certain measures are taken, including the market being clarified for buyers by a differentiation between biodiversity offsets and voluntary credits, and ensuring that terms are used correctly in regulations/guidelines. There is a need to design and agree on global guidance for the claims corporates can make based on credit purchases. There should be sufficient global oversight and regulatory enforcement.

On the supply side, less-rigorous verification for biodiversity credits using a pragmatic approach that balances measurement/accuracy of impact with costs, ease of operation, and community comprehension and engagement could stimulate the pipeline of projects. While integrity principles; governance; and monitoring, reporting, and verification are important, excessively high project costs should be avoided. There are concerns that current third-party standards may counterintuitively be contributing toward greenwashing risk by being so rigorous that they are perceived as enabling offsets, diverting attention from the need for voluntary contributions to biodiversity.

There needs to be improved involvement of and benefits to indigenous people and local communities, including locally led governance structures, steps to ensure that a fair proportion of the credit price goes toward communities, and cooperation on monitoring and education. Possibly certain “unlocks” that would allow biodiversity credits to be used as biodiversity offsets, under rigorous guidance and governance, should be permitted.

To address the biodiversity funding gap, two instruments hold significant promise: biodiversity offsets and “verified” community-driven conservation philanthropy that will reassure corporates about the use of their funds and the impact they are having. The World Wildlife Fund’s “Conservation Performance Payments” is a unique example of such an initiative.

Conclusion: Biodiversity Credits Need to Be Considered within a Broader Portfolio

In our view, the efforts required to adequately scale biodiversity credits are significant relative to their expected demand. While every penny counts, and biodiversity credits should be used to fulfil niche use cases for critical and relevant biodiversity conservation and/or restoration projects, it is important to emphasize that biodiversity credits are only one of many different financing mechanisms for nature preservation.

The collective efforts of the conservation community may be better spent on developing other, more promising tools to unlock short-to-medium term financing for biodiversity. To achieve systemic change at the magnitude that is necessary in the coming decades, every tool is needed.

All stakeholders should be considering biodiversity credits within a broader portfolio of nature investments. To increase private sector funding for biodiversity, we see two instruments with higher potential to significantly move the needle on the financing gap: expanded and more robust biodiversity offsets and more “verified” community-driven conservation philanthropy. For further information, kindly see the full report, grouped by ten sections of insights.