This article was developed in collaboration with Professor Neil Stott and Sophie Harbour of the University of Cambridge.

The first dire effects of climate change are already upon us. The ongoing rise of temperatures around the world has led to an increase in severe storms, floods, and droughts on every inhabited continent.

Among the most consequential effects of these changes in water patterns is climate mobility—the voluntary movement or forced displacement of people from their homes in search of greater safety, cleaner water, adequate food, more sustainable livelihoods, and respite from climate-driven conflict.

Climate mobility, both within countries and across national borders, is rising. In 2022, storms, floods, and droughts caused 99% of the disaster-related displacement of people within their own countries. And unless we slow the current trajectory of global warming, and thus the impact of water-related threats to entire populations, the number of people affected will only increase.

Our recent report on climate mobility analyzes the climate-related risks posed by changes in water patterns and their consequences for the forced and unforced movement of people. The goal: to specify where those risks are greatest, who will be most affected, and what steps need to be taken to reduce the adverse impacts.

Cause and Effect

Climate mobility occurs in response to a complex set of economic, sociopolitical, and ecological factors that are likely to worsen as the earth’s temperature increases. Disruptions in the natural water cycle caused by droughts, storms, floods, and other water-related disasters can trigger crop failure, degrade and erode soil and surrounding land, damage infrastructure and property, and significantly alter ecosystems. Changing water patterns can also affect the quality and quantity of water, which in turn can lead to economic and political instability, further disrupting a society’s capacity to mitigate and adapt to the effects of global warming.

The impact of water-related climate change in Somalia, for example, has been severe. Long-term droughts have caused the price of food to skyrocket, leading to what experts term a “crisis” level of food insecurity. Deteriorating social, political, and economic conditions, including weak governance and ethnic tensions, have led to prolonged conflict in the country, made worse as terrorist groups turn water into a weapon, destroying infrastructure, blocking access to water sources, and poisoning wells. As a result, more than 1.6 million people have been involuntarily displaced over the past several years.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on climate change and sustainability

Risky Outcomes

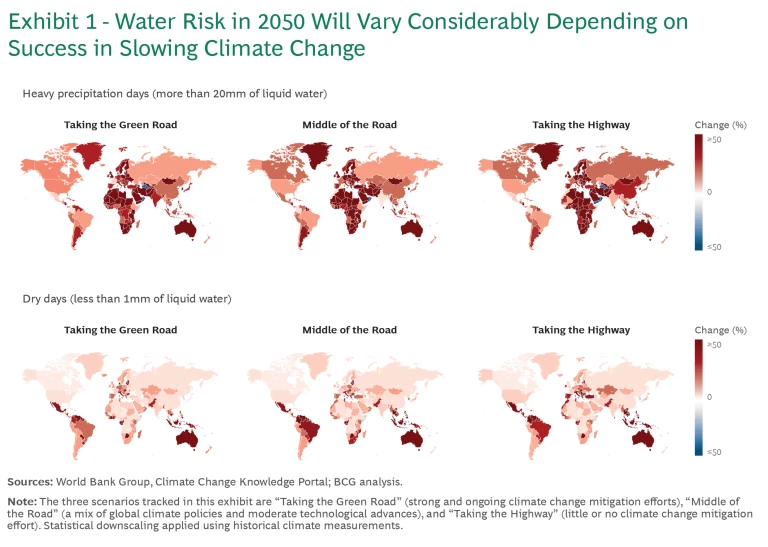

Where are the risks of increased droughts, floods, and storms brought about by climate change most severe, and how will those risks impact climate mobility? We based our model of climate-induced changes in water patterns and the resulting internal and external movement of people on scenarios that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change developed to project the possible future impacts of climate change, depending on the global community’s willingness and ability to slow carbon emissions. The scenario called “Taking the Green Road” assumes strong, ongoing efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, for example, while “Taking the Highway” assumes far less vigorous emissions mitigation efforts and continued high dependence on fossil fuels. “Middle of the Road” assumes a business-as-usual path that falls approximately midway between the other two.

Exhibit 1 maps the flood and drought risks that will exist in 2050 across all three scenarios. Africa, Australia, the Middle East, and Central Europe are at highest risk of increased flooding across all three scenarios, although the frequency of such events will likely increase more under the most severe scenario than under the other two. As for drought risk, Central Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia are most susceptible, but the risk will rise significantly for other regions as well in the absence of stronger climate mitigation efforts.

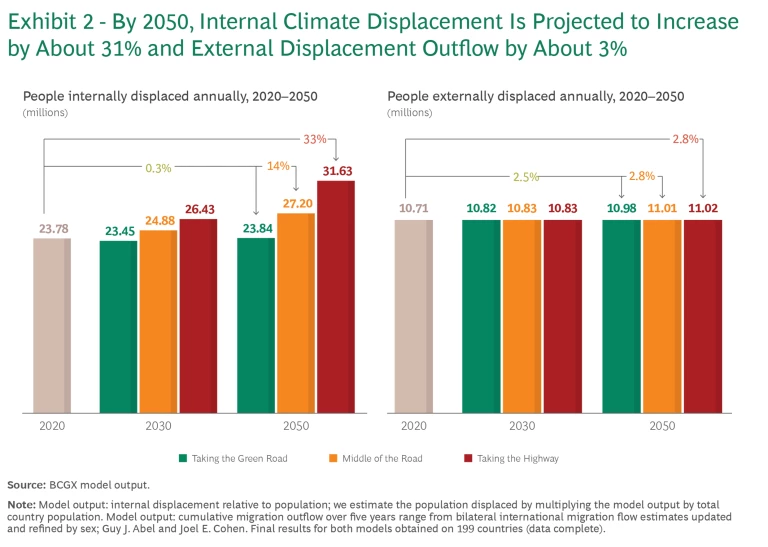

Collectively, these risks will result in considerably higher levels of involuntary displacement in coming years. The total displacement of people across national borders will increase by at least 2.5% over 2020 levels in every scenario, leading, under the worst-case scenario, to the forced movement of 11 million people. (See Exhibit 2.) The impact on internal displacement will be even greater: in the Taking the Highway scenario, nearly 32 million people will be forced to move, and even in the best-case Taking the Green Road scenario, almost 24 million people will be forced to move elsewhere within their home countries.

Slowing the Pace

Given the interdependent environmental, economic, and social factors that lead to climate mobility, reducing the impact of climate change on where people can survive and thrive isn’t just a matter of trying to lower the global level of GHG emissions in hopes of slowing global warming. Climate change is already a reality, and it is already forcing people to move. So besides reducing carbon emissions, we must use and manage the world’s water supply more effectively. In addition, we must implement a range of socially beneficial actions and policies that can alleviate the impact of water-related disasters and help people adapt to them.

To that end, we recommend taking action in three areas: increasing water resilience, boosting social resilience, and bridging the gap between them.

Increasing Water Resilience

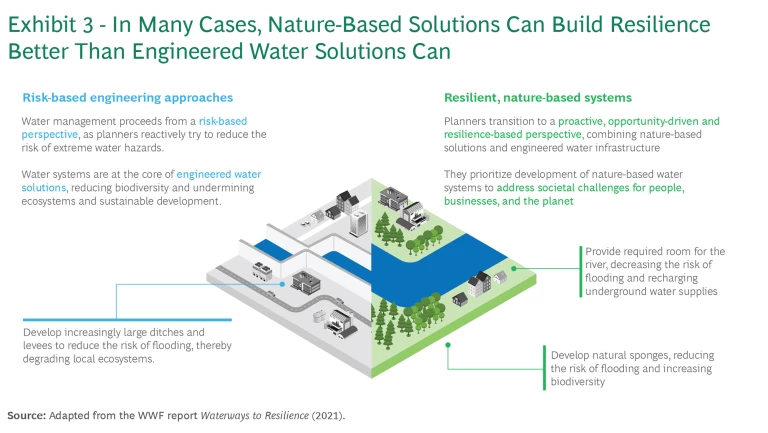

An approach to water management that depends on designing major engineering projects to reduce the impact of water-based disasters is not viable in the long term. Instead, we must design resilient, nature-based solutions that use the power of nature alongside existing infrastructure to adapt in the face of evolving patterns of water-related events. (See Exhibit 3.) At the same time, we must begin thinking of water as part of the “commons” and treat access to fresh clean water for both agricultural use and personal use as a human right, rather than as a commodity to be exploited for private profit. Finally, we must provide access to a range of digital tools and platforms that can enhance resilience and adaptation across the water value chain. These tools include sourcing and distribution technologies, such as water storage and streamflow forecasting; real-time water quality and usage monitoring; precision irrigation and regenerative farming techniques; and cost-efficient wastewater processing and reclamation.

Boosting Social Resilience

Improving water resilience alone isn’t be enough. We need to ensure that the gains are long-lasting and that the benefits are evenly distributed. Public institutions can become more dynamic and flexible in how they respond to water-related events that could trigger climate mobility. Planners can design policies in collaboration with all stakeholder groups to avoid conflicting goals, and deployed consistently. And because the adverse effects of water-related disasters tend to be very localized, policymakers can also look to local communities for local knowledge and governance mechanisms that can enhance water resilience and build trust in proposed solutions.

Bridging the Gap

Collaboration is the key to successfully reducing the impact of changes in water patterns and adapting to their effects. Academics can work together with practitioners and local communities to inform their research into the risks, causes, and effects of water disasters and to help them design better solutions. Stakeholders can team across organizational boundaries to bring together ideas, people, and resources that can lead to lasting change. Finally, mitigating the causes of climate mobility will require innovative financing mechanisms, including loans, grants, banking products, government guarantees, and alternatives such as biodiversity and carbon credits. It is crucial to structure these arrangements to benefit people in need on the local level.

Working Together

Climate mobility is what’s known as a “wicked problem” because it is so complex—with so many interrelated causes and effects and so many potential unintended consequences—that assessing and managing the risks and mitigating the impacts is dauntingly difficult. But as the planet warms and the likelihood of climate mobility increases, we have little choice but to find ways to limit the causes and slow the effects.

The authors would like to thank Selda Dagistanli, Jarrod Pendlebury, Lucy Caines, Peter Waring, Samantha Murphy, Nicole Helwig, Tiril Rahn, Janet Rogan, David Durand-Delacre, Aline van Driessche, Kenza Tazi, Dr. Robert Rouse, Daniella Bostrom, Richard Lee, and Sibi Lawson-Marriott for their contributions.