Excitement is building in mining. Population growth and GDP growth—perennial demand drivers for minerals—continue to fuel worldwide demand. But more important, the global effort to transition to an electrified economy represents a potentially historic growth catalyst. Recognizing this opportunity, a new class of investors are infusing considerable capital into the industry.

Yet significant challenges loom. The uncertainty of an economic slowdown in China, fracturing geopolitics, the shift away from fossil fuels, increasing regulatory barriers, and mounting social resistance complicate the landscape both politically and practically. With these growing difficulties, and amid so many disparate, hard-to-gauge impacts, pursuing value-accretive growth in mining requires a new approach. Over the past decade, a group of new industry darlings have shown how it can be done, outperforming the majors by following strategies that have enabled them to navigate the shocks of an increasingly volatile environment.

But maturity needn’t impede the agility these winners have used to advantage. The five actions described in this article can set mining companies on a more promising pathway to value-accretive growth. By pairing revenue growth with margin expansion, miners can regain investor confidence.

Performance Woes Have Shrunk the Investor Base

Mining companies’ subpar performance throughout previous commodity cycles have rattled investors. Throughout the most recent cycle, most companies were unable to produce above-market returns. And although the investors we speak with accept the inherent volatility of the industry, performance through the cycle has nonetheless been disappointing.

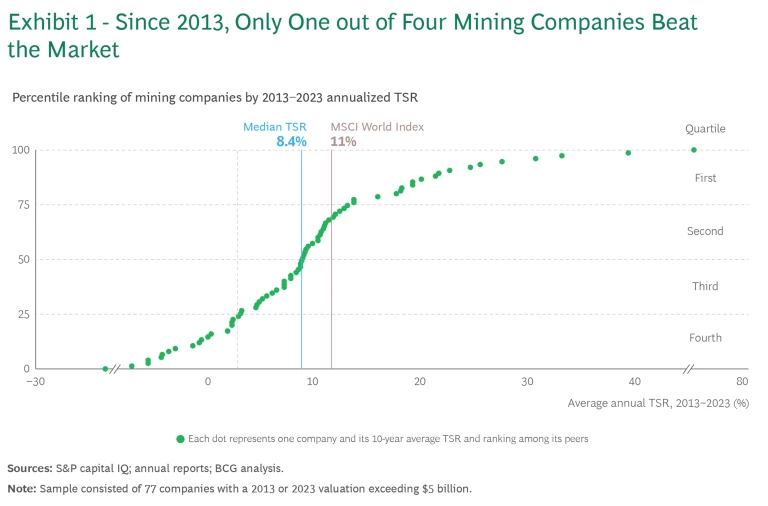

For this article, we analyzed 77 mining companies spanning all key regions, commodities, and listing domiciles. Our sample includes companies with a market cap greater than $5 billion at either year-end 2013 or year-end 2023. Over the past decade, the post super-cycle downturn hurt many mining companies and their investors. As Exhibit 1 shows, only about one in four companies delivered a total shareholder return (TSR) greater than the bellwether MSCI World Index and the industry overall underperformed by about 2.5 percentage points. (See the sidebar “How We Analyze Company TSR.”) Return on capital has been equally inferior, generally below the weighted average cost of capital. In their pursuit of growth, miners triggered price crashes that destroyed value.

Given this performance, it’s not surprising that many investors commonly view mining companies as a “trade,” and that many active and specialist investors have abandoned the market.

How We Analyze Company TSR

All of these factors interact—sometimes in unexpected ways. A company may grow its earnings per share through an acquisition and yet not create any TSR because the new acquisition erodes the company’s margins. And some forms of cash contribution (for example, dividends) may affect a company’s valuation multiple more positively than others (such as share buybacks). Because of these interactions, we advise companies to take a holistic approach to value-creation strategy.

The Increasing Pressures of Geology, Climate, and Geopolitics

Mining companies today are contending with a triad of growing pressures, both physical and societal.

Geology. Grade fade has become a persistent trend. Copper and gold mined ore grades have declined globally on average by roughly 20% and 15%, respectively, from 25 years ago. Miners are thus under intense pressure to compensate for the impacts on cost and productivity. Ore grades in frontier jurisdictions (regions with a low level of historical exploration, fewer existing assets, or less established mining regulations; e.g., Mongolia and Pakistan for copper) are often significantly higher. Over the past five years, drilled grades for copper in frontier locations were 1.5 to two times higher than the global average and three to five times higher than grades in such copper hubs as Peru and Chile. But mining in these regions calls for a different approach, coupled with a different risk appetite.

Climate. Extreme and unpredictable weather events are becoming more commonplace, increasingly disrupting, and at times are impeding operations. For example, forest fires have forced mine shutdowns in western Canada (British Columbia and Alberta) in the past few years. In addition, droughts have halted production at potash sites in Germany and tropical cyclones have disrupted coal and iron ore production in Western Australia.

Geopolitics and Policy. Environmental and social concerns have intensified the pressures on legislators and policymakers to impose more restrictions on—or altogether block—mining activity for critical minerals. The list of actions keeps growing: Zimbabwe’s ban on unprocessed lithium exports in 2022; China’s export restrictions on antimony, graphite, gallium, and germanium over the past two years (actions that are prompting increasing discussion about government intervention in metals markets); Panama’s rescinding of a copper-mine permit in 2023; Mexico’s recent consideration of a ban on open-pit mining; and the US government’s limit on incentives for EV batteries in which less than half of their sourced or processed critical mineral value is mined domestically or from friendly trade partners.

Similarly, permitting has grown increasingly difficult, creating more hurdles for project development. (As it is, more than 90% of exploration projects fail to turn into physical mines.) According to BCG’s most recent analysis, it takes on average two to three times as long for a copper mine to receive a permit today as it did in 2006. (An April 2024 S&P study determined that the average lead time for mines that came online between 2020 and 2023 was 18 years). And most established mining jurisdictions fail to meet their own permitting deadlines. More generally, ESG (environmental, social, and governance)—specifically the “social”—has had a growing and outsized impact on permitting as NGOs and other organizations pressure governments and regulators to deny approval. Mining companies therefore need to persuade broader society, not merely regulators and local stakeholders, of the need for and benefits of a proposed mine. (See the sidebar “Proactive Community Engagement Boosts Local Support.”)

Proactive Community Engagement Boosts Local Support

Some, like NWP Coal of Canada, are proactively involving indigenous communities in the development stage. In a signed agreement, NWP has given Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi'it (also known as the Tobacco Plains Indian Band) the right to veto its proposed mine, allowing them to act as regulator and embedding them into the project as a joint developer. In the 2000s, farming communities in Peru violently opposed the Quellaveco mine in Peru due to its potential impact on water resources. Along with regional authorities, Anglo American held a series of multi-stakeholder roundtables beginning in 2011. Ultimately, stakeholders and international institutions granted the company social license to operate, thanks to a process some now view as a new standard for governance.

1. Solène Rey-Coquais, “Territorial Experience and the Making of Global Norms: How the Quellaveco Dialogue Roundtable Changed the Game of Mining Regulation in Peru,” Extractive Industries and Society, March 2021.

Competition from Industry Darlings

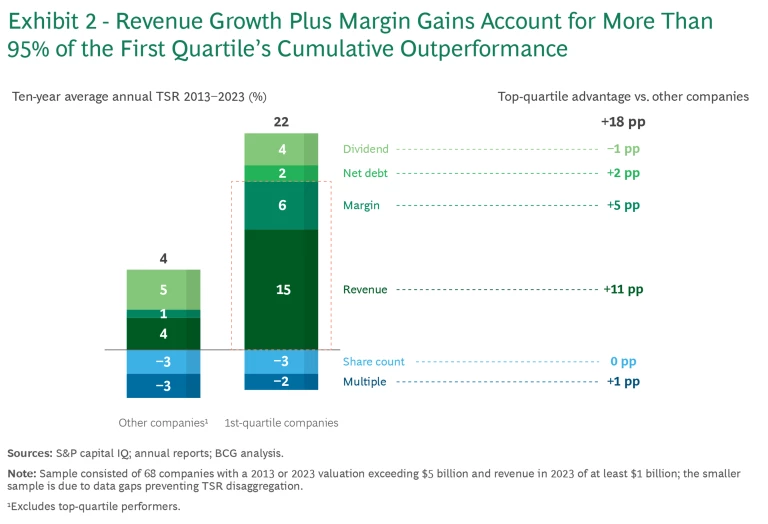

Yet amid these formidable challenges, a set of industry darlings have found a way to win consistently year after year. These top-quartile performers, many of them based in frontier jurisdictions, achieved an average TSR of 22% over the past decade (year-end 2013 through year-end 2023), outperforming the other industry participants by 18 percentage points. (See Exhibit 2.)

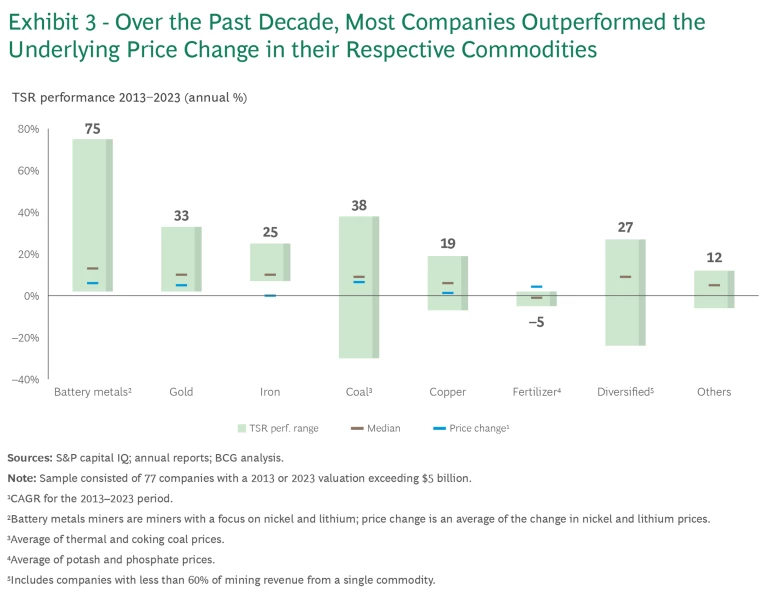

They have done so defying the conventional view that commodity choice is destiny. Certainly, price run-ups in specific ores and metals affect outcomes, but these winners come from across the commodity spectrum. (See Exhibit 3.)

In the latest ten-year period, these high-performing companies managed to deliver top-quartile returns. In fact, in backtests, many of them produced top-quartile returns over various ten-year periods throughout a 20-year span. (See the sidebar “What Separates the Darlings from the Rest.”)

What Separates the Darlings from the Rest

- They had outsized revenue growth, achieved through production growth rates eight times that of industry peers.

- They were around 40% more likely to increase their margin.

- They were about 50% more likely to make acquisitions.

- They were more likely to invest programmatically through the cycle and were better at avoiding pro-cyclical spending sprees.

- They commanded a 20% higher valuation (although valuation did not materially influence TSR).

- They were 70% more likely to maintain dividends through the cycle.

Australia-based Northern Star, for instance, has grown from a junior to a competitive midmarket player in gold over the past decade, generating leading TSR through a series of acquisitions. Zijin, the China-based copper company, has leveraged its government trade relationships in more nascent mining jurisdictions (such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia) to de-risk investments with, among other things, infrastructure support. This strategy, along with making acquisitions in these regions, was key to the company’s growth.

Saudi Arabia’s Ma’aden has expanded into new commodities and down the value chain into smelting, via organic growth and joint venture partnerships. In the period 2013–2023, Mexico-based Southern Copper has achieved two decades’ worth of top-quartile TSR performance through brownfield growth expansions and cash flow contribution to TSR. And in the last ten years, Fortescue, one of Australia’s largest iron ore producers, has likewise earned long-term top-quartile TSR performance, powered through a combination of growth, margin improvement, and cash flow contribution.

Interestingly, the new winners’ results hold true even when smaller companies are excluded from the mix. If we focus on the industry’s majors (those with a market cap exceeding $30 billion in either 2013 or 2023), we see similar results: the average top-quartile miner delivered a TSR of 25%, while the other majors achieved only 7%. As with the broader sample, margin and revenue expansion remain core to TSR. However, with larger organizations, dividends and capital returns play a greater role in TSR performance, serving as the foundation of returns.

Why the Old Guard Companies Are Faltering

Over this same ten-year period, the industry’s majors have struggled to deliver value-accretive growth. Their median revenue CAGR of around 4% lags the industry’s overall 5% and pales in comparison to the industry darlings’ 17%. Underperformers have been unable to increase production to a meaningful extent, and margins shrank, on average, by around 20%.

We see two reasons for the majors’ struggles. First, their strategic choices have limited their degree of freedom. The focus on large, long-life, and low-cost assets may have improved their resilience through cycles, but good assets alone do not yield TSR outperformance. The focus on low-risk jurisdictions has constrained their ability to quickly develop and access high-grade ore. Furthermore, their reluctance to invest in smaller (and somewhat easier to build) mines has made it harder for them to adapt to development challenges and consistently deliver steady growth.

In addition, diversification has increased the complexity of the majors’ businesses without an apparent corresponding payoff for shareholders. As BCG has long argued, the more complex an organization is, the tougher it is to beat average revenue and margin growth—the two most important drivers of TSR. By complexity, we mean everything from organizational structure and business systems to different types of operations and value-chain integration. In mining, complexity also means commodity diversification, historically an approach to reducing risk. Recently, large miners have worked to reverse this trend, visibly simplifying their commodity mix in the past three to five years. But general business complexity continues to grow as miners scale, manage more regulation, and contend with grade fade.

Our analysis validates our general finding: diversification (and its associated operational complexities) has simply not delivered risk-adjusted returns benefits for investors. Of the companies we analyzed with a valuation of at least $5 billion in 2013 or 2023, the risk-adjusted TSR of diversified miners was 40% lower than the pure-play

It’s not enough to own a world-class asset. “Right place, right time” is not a viable strategy in a volatile, dynamic global operating environment where demand is hard to predict, ore grades are dwindling, and regulatory and social roadblocks often thwart the progress needed to advance the energy transition and socioeconomic progress.

Five Winning Actions

Despite the considerable obstacles and uncertainties, there is a path forward. We’ve identified five actions that mining companies can take to achieve value-accretive growth and improve the fundamentals of their business.

Refresh your approach to investments and portfolio risk. Delivering top-quartile returns in the decade ahead will require many miners to reconsider their historical risk tolerance for project types and locations—geological realities mandate it. The next decade’s winners are unlikely to succeed through organic growth alone. Having a playbook for value-creating M&A is therefore critical. But committing to new locations or new mining methods, or undertaking M&A will not be easy for management teams. By taking a scenario-informed approach, you will be better positioned to do so.

Double down on operational performance. To deliver on the top and bottom lines, continuous improvement is a must. TSR measures improvements and resets each year, so if you’re not improving, your value creation will be muted.

Zero-base your organizational structure. The best way to root out inefficiency and maximize productivity is by assessing and justifying every role and activity from the ground up. A zero-based approach can simplify processes, eliminate waste, and free up resources for more strategic uses—including shifting people to more high-value work.

Revisit your approach to talent. Companies need to install “generative” leaders who recognize that attracting and retaining talent today requires more than solid compensation and benefits. Research shows that workplaces that offer emotional fulfillment and the opportunity for personal growth can hold on to valuable employees. Moreover, there’s a need for new skills and capabilities; for example, long-term mine planners need to more thoughtfully consider environmental impacts and community relations that go beyond traditional economic and geological factors.

Win over investors as you do your customers. Too many mining companies have undercut their credibility with investors by failing to deliver consistently on their volume and cost estimates from quarter to quarter. And these companies in general need to overcome the widespread perception that they are a merely a “trade.” Establish a clear, compelling investment thesis with transparency about your TSR formula—one that delivers leading returns throughout the cycle.

It behooves all mining companies to take these actions to heart. But the largest organizations in particular must critically reexamine their businesses and simplify how they operate. To stave off the threat from the industry darlings and regain their industry leadership position, they must do away with unnecessary processes and adapt and accelerate their decision making. They need to acknowledge that TSR is a reward for improvement, and that a world-class asset can no longer gain value by itself.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ross Middleton, Karthik Valluru, and Bilal Saleem for their contributions to this article.