After a period of relative stability, the world is becoming more volatile and uncertain. Pillars of stability in Europe such as resilient economies, robust public institutions, and energy security are being challenged every week, and recent changes in US foreign policy have thrown long-established alliances into question. This change has major implications for European defense and security institutions—including ministries of defense (MoDs) and alliances such as NATO—as well as for defense contractors, which must shift from discretionary operations to heightened readiness.

Given these shifts, MoDs will have to adjust their risk appetite and become more agile and proactive. This includes a greater willingness to share both upside and downside risk with contractors, particularly when it comes to innovation and new commercial models. By embracing risk sharing, MoDs can accelerate the adoption of cutting-edge technologies, which will allow them to scale up their defense capabilities, operate at a faster tempo, and adapt to emerging scenarios.

Our work with MoDs, defense manufacturers, and other stakeholders suggests that defense enterprises can succeed by strengthening command and coordination, boosting industrial capacity, and accelerating innovation.

Challenges in Six Areas

Defense enterprises face six broad challenges in adapting to the current environment.

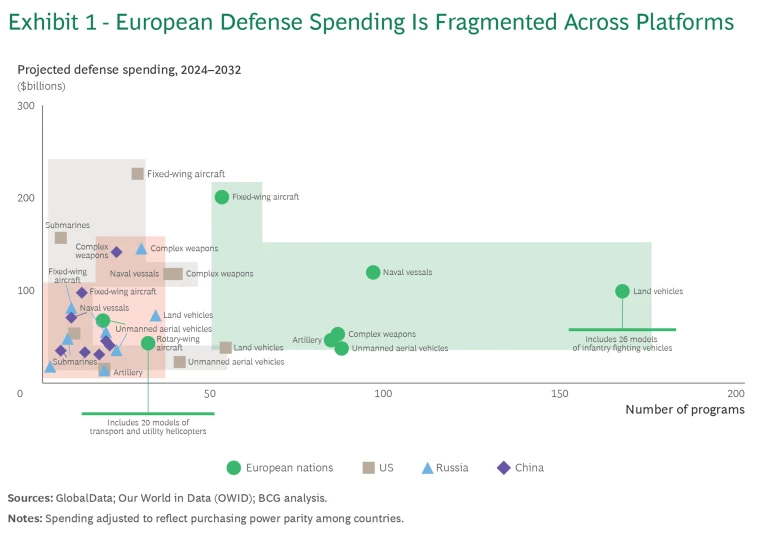

Lack of Inoperability Among Allied Nations. In a high-performing alliance, each party plays to its strengths and collaborates to build capabilities for the overall group. But countries inevitably have their own agendas, which compete against the strategic objectives of the alliance. One consequence is that many defense platforms have national variants that increase complexity without yielding advantages in the field. (See Exhibit 1.) For example, the US has 1 main battle tank, while European defense entities have 17. The discrepancy among destroyers and frigates is nearly as pronounced—4 in the US and 29 among European defense entities.

The NH-90 helicopter is an extreme example. It was originally designed in the 1990s for NATO forces with two variants: one for naval operations and another for transport. But due to individual MoD procurement processes, there are an estimated 47 variants in use today, including versions with different cargo holds, cockpits, and even engines. Despite the helicopter’s proven track record, the expansion in variants has led to sharp increases in maintenance costs and production delays, leading Australia, Norway, and Sweden to cancel orders.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on the public sector

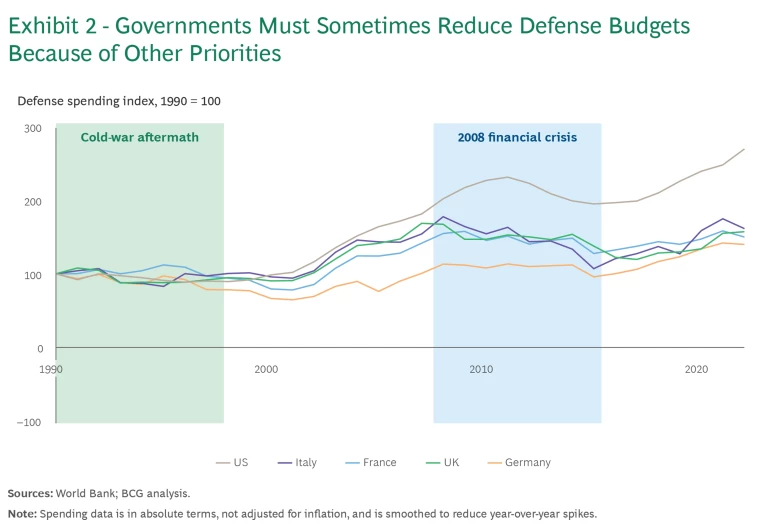

Insufficient Coordination Between Government and Industry. In Europe, many MoDs are not equipped to coordinate with industry on defense priorities and funding—mainly because of a fractured strategic planning process, volatile budgets, and poorly developed and communicated military requirements. In part, this is the result of fiscal pressures and competing priorities. For example, economic crises can require governments to reallocate resources away from defense budgets in order to sustain social programs. (See Exhibit 2.) The lack of alignment with government prevents the defense industry from committing to long-term investments to scale up capacity.

In addition, MoDs and OEMs have competing priorities. Defense ministries tend to tightly control the technical and operational specifications for defense projects—an approach that can stifle innovation and flexibility. At the same time, defense industry players have high nonrecurring costs, creating an incentive to prioritize efficiency by saturating existing capacity. As a result, European forces are oversupplied with nonessential equipment.

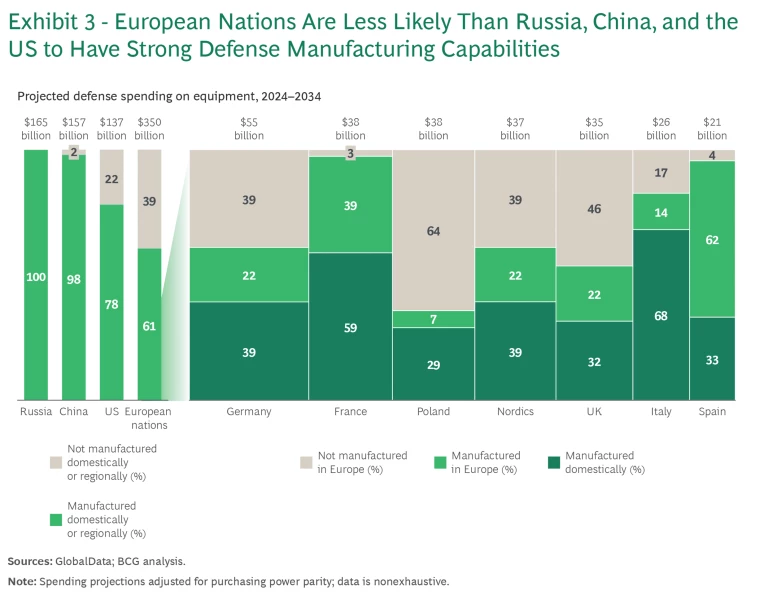

Weak Coordination Among Nations. European nations face significant challenges in coordinating their defense strategies, both within NATO and at the regional level. A complex web of more than 80 active alliances and defense cooperation agreements, each involving at least one European nation, only adds to the difficulty of forging a unified approach. This has led to fragmented and decentralized procurement in major defense programs. Instead of pursuing a cohesive European defense framework, nations often resort to a disjointed mix of equipment manufactured within and outside of the region. Around 40% of European defense spending goes for arms acquired from outside of Europe. (See Exhibit 3.)

Minimal Insight into Current Readiness Levels. Military and government leaders often have limited awareness of current readiness levels, leaving them unable to spot or rectify emerging issues. For example, in the case of many defense assets, roughly 60% of the total life cycle cost is sustainment, rather than the original acquisition cost. But without an understanding of mission-capable rates for key assets, the correct parts cannot be specified, contracted, or deployed to meet the target levels.

Some national and regional initiatives are in place to create greater transparency, but many countries still lack integrated systems to provide real-time, granular information about current defense capabilities.

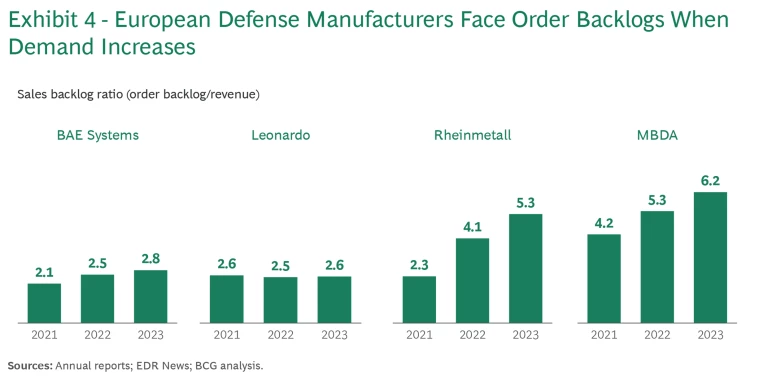

Inflexible Industrial Supply Base. In many European countries, defense manufacturers do not have the kind of flexible production lines that would allow them to scale up in response to new threats. This is exacerbated by the lack of government–industry coordination. As a result, sudden spikes in demand have led to order backlogs. (See Exhibit 4.) The problem of inflexible capacity is particularly acute when new defense programs are ramping up into full production. As a result, more than 75% of aerospace and defense programs exceed scheduled timelines, and more than 40% run over budget.

Securing the physical resources required to sustain production—through stronger collaboration between defense and adjacent industries or coordination with partner nations—is an essential task of government. What’s needed is a different mindset and a deeper understanding of the implications for industry of government requests to build specific capabilities.

Lengthy and Incremental Innovation Cycles. Many European nations are failing to keep pace with rapid changes in the threat environment. Lengthy development cycles are a result of issues across the entire innovation process, including limited coordination with suppliers and fragmented funding. In a recent survey, BCG found that MoDs increasingly see innovation as a strategic priority and are more willing to work with startups and innovation accelerators. Yet this is not translating into results in the field, as reflected in these findings:

- 88% of respondents reported that linkages between innovation focus areas and mission strategies, goals, or needs are not sufficient to yield tangible outcomes.

- 66% of respondents reported not having an innovative culture that encourages risk taking.

- 56% of respondents reported a lack of implemented approaches, methods, and systems to source ideas from end users.

Three Priorities to Improve European Defense Capabilities

These significant barriers point to three main areas of activity that MoDs, defense contractors, alliance members, and other stakeholders should prioritize.

Strengthen strategic command and coordination. Industry and government must collaborate more effectively, sharing performance data and insights and aligning on overall strategic and tactical goals—with military capabilities as the primary objective. To that end, defense entities can take several steps to strengthen coordination and collaboration across the ecosystem:

- Establish a centralized control point to provide MoDs and industry with a view of baseline data—such as mission-capable rates, production rates, stock levels, and other key metrics—that can inform decision making.

- Develop long-term defense budget plans that include a baseline funding level, along with a supplemental amount that can be adjusted according to economic conditions and political priorities. This approach offers the necessary certainty for long-term planning by suppliers, while still accommodating changing requirements at the national and international level.

- Design procurement models that can enhance coordination between MoDs and industry. For example, the UK MoD’s complex weapons program, a consortium of companies including MBDA, Thales, Roxel, and QinetiQ, aims to improve coordination between the ministry and industry by optimizing the supply chain and rationalizing inventory. In its first phase, the program has increased the choice of military capabilities for the UK and Europe and generated £2.6 billion in savings for the MoD. In mid-2024, the program was renewed with a ten-year planning horizon and £6.5 billion in planned investment.

- Improve joint procurement planning and execution across alliances to prioritize the “greater good” over national interests. Through collaboration by MoDs at forums like the NATO Defense Planning Process, systems can be made more interoperable, requirements standardized, and procurement pooled.

- Develop investment strategies to increase capacity—a go-to-market approach tailored to MoDs’ key industrial and security strategies and focusing on preemptively developing capacity to meet anticipated needs, including localization of capacity.

Boost industrial capacity. Across alliances and nations, leaders can take several steps to boost industrial capacity in a coordinated, interoperable way:

- Set a North Star production target at the platform or submodule level, and continuously measure progress. Establish three to five easily measurable, guiding KPIs (for example, end-to-end production turnaround time) that are tracked and automatically updated, linked to a central command point, and cascaded down to the frontline. To keep teams focused on meeting these KPIs, MoDs must make sure that the right contractual incentives are in place.

- Adopt best practices from the private sector to enhance agility. Implement cost-plus practices and adopt advanced manufacturing and modular design to become more flexible in scaling capacity.

- Integrate suppliers to meet evolving requirements. Pull the most important suppliers into discussions early in the development process, ensuring that they are intimately familiar with the program’s path to full production. Over the long term and as programs scale, OEMs need to establish supply chain control points and leverage AI to provide end-to-end visibility and material forecasting across the full value chain.

- Secure a resilient supply chain for critical components by consolidating lists of high-performing suppliers and establishing contingency plans (such as call- or option-like agreements).

- Empower the workforce and minimize tribal knowledge. Review recruiting, hiring, and retention processes to address the risk of labor shortages during ramp-up. Improve the readiness of the current workforce by introducing GenAI tools to provide on-the-floor assistance. Document routine procedures and cross-train to prevent overreliance on highly skilled workers and “brain drain” when those workers leave.

Accelerate the pace of innovation where it matters most. While the importance of innovation is growing, European defense entities have not been able to innovate effectively, primarily because processes tend to be slow and incremental. The tech industry teaches that the adoption of new products starts slowly, then hits an inflection point of exponential growth. Incumbents typically defend their position and watch technology pass them by.

Defense contractors can avoid this trap by embracing new business models. A good example is Anduril, a US defense technology company that specializes in autonomous systems. The company was founded in 2017 and has a model unlike that of legacy contractors. It self-funds most product development and attracts leading technology talent. Contractors can learn from that model and rethink their approach to talent and leadership. They can also draw funding from new investors such as venture capitalists, build low-cost distributed systems, and develop open architectures that allow new partners to join and contribute.

Other measures to accelerate innovation include the following:

- Utilize agile development, digital twins, and modern test and evaluation tools to boost innovation and decision-making agility and validate mature solutions.

- Review security policies for R&D sharing. Work to harmonize international regulatory frameworks in order to facilitate smoother knowledge sharing and collaboration among allied nations by aligning policies, standards, and protocols.

- Give startups and small and medium-sized enterprises better access to MoD programs. Create mechanisms for these companies to collaborate more directly with prime contractors, including helping them take advantage of assets such as testing facilities and engineering know-how.

- Bring engineers directly onto the manufacturing floor to observe and provide input throughout prototyping and initial production. Additionally, ensure a strong relationship between business development and engineering teams to avoid committing to requirements and timelines that may not be feasible and result in cost and schedule overruns.

- Tap into—and learn from—the venture capital industry. Venture backing encourages a high-risk, high-growth appetite and supports bets on immature but promising technology that has not been fully developed in-house.

- Where applicable, increase risk appetite to speed innovation—such as by removing obstacles to the acceleration of product development timelines. For example, the Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missile and the High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) were both integrated into Ukrainian platforms very quickly, overcoming the obstacles that often slow the implementation of defense systems. MoDs can accelerate innovation by relaxing some of the technical constraints that aim for perfection and sophistication, while still maintaining those that ensure safety.

The world is changing and the defense sector must change as well. By focusing on command and coordination, industrial capacity, and innovation, MoDs, manufacturers, and alliances can do more, move faster, and respond more readily to rapidly evolving military requirements. That will allow them to emerge better equipped to fulfill their mandate: protecting their sovereign states in a more uncertain world.