Less than a decade ago, the contours of international commerce were still being shaped by an ambitious free-trade system aimed at opening new markets for companies and workers. These days, geopolitics and economic security considerations are becoming the defining forces.

New research by BCG, which has been tracking these shifts in global trade since 2018, reveals just how sharply geopolitical rivalries, alliances, and aspirations are rewiring the global economy. (See “ About Our Research .”)

Although we project that total world trade in goods will keep growing at an average of 2.9% annually for the next ten years, the routes goods travel will change markedly. (See the interactive.)

How Trade Flows Between Nations and Regions Will Change by 2033

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

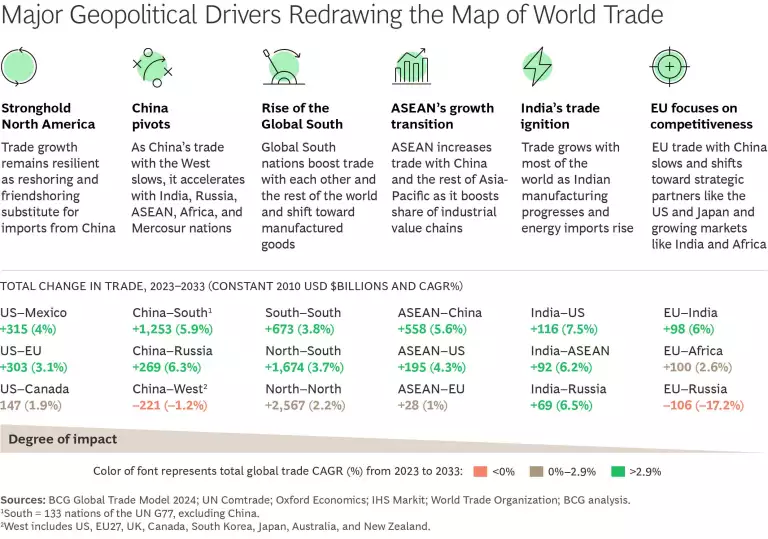

Based on our analysis of trade and economic data for more than 150 countries, as well as the expected impact of recent national and regional policy initiatives, we have identified several tectonic shifts in global trade corridors:

- North America is solidifying into a resilient trade bloc that will continue to reduce its dependence on Asia, especially China. For now, this substitution of supply sources seems to be working.

- China will emerge as the stronger trade partner for the rest as its commerce with the West

slows.1 1 West includes US, EU27, UK, Canada, South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Increasingly, indigenous technologies and deeper economic relationships with fast-growing emerging markets will drive growth. - The Global South will rise as a force in world trade, powered by dynamos such as India and Southeast Asia, as developing nations contribute more to global supply chains and develop new

capabilities.2 2 Global South refers to the 133 member countries of the United Nations’ Group of 77, excluding China. South-South trade will also surge and is moving beyond exporting natural resource-based commodities to more sophisticated manufactured goods. - The European Union’s trade growth with China will largely stagnate. The region is becoming more reliant both on long-standing trade partners such as the US and Japan and emerging markets such as India, Turkey, and Africa.

Major changes in US trade policy under the incoming administration of President-elect Donald Trump would significantly increase the magnitude of these shifts and add to the cost of US imports from certain markets. (See “Estimating the Impact of Higher US Tariffs.”)

Estimating the Impact of Higher US Tariffs

For illustrative purposes, we modeled the direct impact of the 60% tariff on Chinese goods, a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico, and 20% on imports from countries in the rest of the world. We estimate that the tariffs would add $640 billion to the cost of importing goods from the top ten US import nations, based on 2023 levels, unless alternative sources are found. (See Sidebar Exhibit 1.) BCG has not yet modeled the impact of all other Trump proposals or potential retaliation from US trading partners. We are closely monitoring developments and will update the Global Trade Model accordingly.

In terms of product categories imported by the US, the greatest impact would be on imported auto parts and automotive vehicles, which would primarily affect trade with Mexico, the EU, and Japan. Consumer electronics, electrical machinery, and fashion goods will be most affected by higher tariffs on Chinese goods. We estimate that a 60% tariff rate would add $61 billion to cost of importing consumer electronics products from China into the US. (See Sidebar Exhibit 2.)

As the period of relative stability and multilateralism that followed the end of the Cold War is replaced by a multipolar era characterized by rising regional powers, changing alliances, economic nationalism, and national security, we expect each of these trends to become more pronounced over the next decade. Business leaders must consider both the risks and opportunities created by evolving geopolitical shifts that will alter their supply chains and business strategies. They will also need gameplans for adapting to disruptive events under various scenarios and capitalizing on opportunities they may create.

We have analyzed several of the major trade shifts we expect to see over the coming decade. (See the exhibit.)

Stronghold North America

The tight trade relationship between the US, Mexico, and Canada, bolstered by years of reshoring, nearshoring, and friendshoring aimed primarily at easing reliance on Chinese imports, is contributing to North American economic growth. We project that annual trade between the US and Mexico will increase by $315 billion by 2033—representing a CAGR of 4%; US–Canada trade will grow by $147 billion as companies serving North American markets shift more of their supply chains to the

Aparna Bharadwaj

This is a modal window.

Aparna Bharadwaj

The US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) and industrial policies, such as the billions of dollars of US and Canadian government incentives for electric vehicles (EVs), lithium-ion batteries, and renewable energy systems , underpin the resilience of what we call “stronghold North America.”

Mexico will continue to attract manufacturing investment as a nearshoring platform for the US and Canadian markets. To realize its potential, however, Mexico will have to invest in more transportation infrastructure, electricity generation, and human capital to address looming bottlenecks.

Another uncertainty, especially for companies considering long-term capital investments, is the USMCA itself, which is up for renegotiation in 2026. Washington is concerned that Chinese firms aim to circumvent high US protectionist barriers against low-cost Chinese EVs and other goods by assembling and exporting them from Mexico, taking advantage of its duty-free access under the USMCA. One issue to watch is whether the US will leverage the USMCA renegotiation to seek to have Mexico screen Chinese foreign direct investment in its North American manufacturing value chain.

Friendshoring is also redefining North American trade relationships. Assuming broadly stable trade relationships, annual US trade with the EU, for instance, is projected to grow by $303 billion, a CAGR of 3.1%, by 2033. In addition to growing US sales of LNG as the EU reduces its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons, much of this growth will be driven by renewable energy technologies. Efforts to cut tariffs and harmonize trade policies in strategic sectors such as cars and advanced manufacturing will also enhance ties. A rise in protectionism in either side of the Atlantic, on the other hand, could slow this momentum.

China Pivots

As China’s trade with the US and EU slows, it’s growing strongly with much of the rest of world. We project that annual two-way trade with the West will contract by $221 billion by 2033—representing an average annual decline of 1.2%. The $159 billion decline in annual US–China trade could be sharper if the US significantly raises tariffs on Chinese goods. At the time of this writing, the situation remains fluid. President-elect Trump has suggested he will impose an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports and has previously proposed setting Chinese tariffs at 40% to 60%. Under the 60% scenario, we estimate that would further reduce US–China trade in 2033 by 27% compared with our baseline scenario. The cost of imported Chinese goods would increase by more than $200 billion if no alternative sources are available and if import volumes remain constant.

We project that China’s trade with the Global South, by contrast, will surge by $1.25 trillion by 2033, representing a CAGR of 5.9%. This shift will support China’s geopolitical agenda of reducing its economic reliance on the West while deepening ties with major emerging markets. It will be bolstered by China’s heavy investment in the Global South through infrastructure programs such as Belt and Road Initiative projects and deeper commercial engagement, which are opening major opportunities for Chinese companies in some of the world’s most dynamic growth markets. China’s trade with the ten nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is expected to account for roughly half of that growth. China has been improving its free trade agreements with ASEAN and with individual Southeast Asian nations. China is also part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free-trade pact among 15 Asia-Pacific nations.

Another indicator of China’s pivot toward the Global South is its relationship with member nations and close partners of BRICS+ , a grouping that includes original members Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa and four new members from the Global South. China’s trade within BRICS+ is projected to account for 44% of China’s total forecast trade growth over the next decade. China will also continue to make greater economic inroads more broadly in Africa. However, rivalries within the grouping, such as between India and China, could limit its success.

As the war in Ukraine continues and the rift between the West and Russia continues to widen, China’s trade relationship with Russia is projected to increase significantly. We project that annual bilateral trade will grow by $269 billion by 2033 (6.3% CAGR). The Power of Siberia-1 and the proposed Power of Siberia-2 pipeline projects, which will increase China’s access to Russian natural gas, are key elements of the growing collaboration. The pipelines would reshape global energy and commodity markets and help cut Russia’s economic reliance on the West. They will also help provide China with an additional market for cars, appliances, apparel, and other consumer goods that Russia previously imported from the EU.

This isn’t to say China’s pivot will be painless. Trade lost through higher US, Canadian, and EU tariffs and outright bans on certain Chinese technology-intensive products—combined with Chinese retaliatory measures—won’t be fully replaced. We project that China’s total trade growth will be limited to 2.7% annually over the next decade, well below the current average real annual GDP growth estimate of 3.8% over the same

There’s also a risk that China’s record trade surpluses generated by its growing excess capacity in several manufacturing industries will trigger a backlash not just by the US and the EU, but also potentially by India and other trading partners.

The Rise of the Global South

One key—and perhaps the least heralded—development in global trade is the growing power of Global South nations. This group of 133 developing nations represents around 18% of global GDP, but 62% of the world’s population. It also accounts for around 30% of global trade.

Global South nations are forming new trade alliances and partnerships that sidestep the US and the EU. This trend is part of a broader geopolitical realignment toward a multipolar world trade system that reduces the influence of—and dependence on—Western markets. BRICS+ is one such grouping. Others include the 54-nation African Continental Free Trade Area, established in 2018; Mercosur and the Pacific Alliance in Latin America; and ASEAN. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which emphasizes connectivity and infrastructure development in the Global South, and the transfer of some production from China to other low-cost nations are also stimulating Global South trade.

We anticipate several major shifts in Global South trade over the coming decade. Although trade with China will continue to grow robustly, we project that the pace will slow to 5.9% CAGR compared to 7.5% over the past five years as indigenous manufacturing processes mature. Annual trade among Global South nations themselves, by contrast, will expand by a projected $673 billion over the next decade; its CAGR over that period will accelerate to 3.8%, compared with 2.8% from 2017 to 2022. Trade between the South and the North will also accelerate, to 3.7% CAGR from 2.3% over the previous five years, expanding by $1.67 trillion over the next decade. In December 2024, for example, the EU and South America’s Mercosur trade bloc announced they had reached agreement on a free-trade pact after over 20 years of negotiations.

The composition of global trade will also evolve as emerging economies advance to more complex industries. Trade within the Global South is moving beyond traditional agricultural commodities, minerals, and energy. Manufacturing sectors such as automobiles, consumer electronics, chemicals, metals, and fashion items are gaining a greater share. A similar trend is seen with Global South trade with industrialized nations’ finished goods.

ASEAN’s Growth Transition

ASEAN is emerging as a major player both within the Global South and with the rest of the world. The region has been among the greatest beneficiaries of production shifts spurred by geopolitics, such as trade tensions between the US and China. Combined trade of the ASEAN nations is projected to grow 3.7% annually over the next decade as the region’s manufacturing capabilities improve and their share of industrial value chains deepen, particularly in sectors such as electronics. To mitigate risks, many companies are adopting “China+X” strategies aimed at diversifying supply chains by investing in ASEAN alongside China. Some ASEAN countries are also helping connect the economies of China and the US by serving as hosts to foreign investment from both nations.

ASEAN’s trade relationship with China is expected to continue to grow 5.6% annually, to $558 billion in 2033. It will be fueled in part by China’s heavy investments in the region, a revised free trade agreement between ASEAN and China, and bilateral pacts between China and Vietnam and Thailand.

That said, ASEAN will likely face some challenges over the coming decade. We project that trade growth with the Europe will flatten, to only around 1% a year, as the EU implements a carbon-pricing system on imports, which will particularly affect ASEAN sectors like metals, cement, and chemicals. The EU is also curbing imports of agricultural commodities harvested from recently deforested land. To remain competitive in the EU, ASEAN companies will need to improve in sustainability.

ASEAN trade growth with the US is likely to moderate as well, to 4.3% CAGR through 2033. Washington might also apply greater scrutiny to goods assembled in ASEAN with a high content of Chinese-made components and materials if they are viewed as circumventing high US tariffs. To sustain its rise, ASEAN will need to develop deeper domestic and regional supply chains. The region must also upgrade its capabilities so that all ASEAN nations benefit from global trade.

India’s Trade Ignition

India is emerging as the other big Global South trade story as it pursues favorable relations with most of the world’s major economies. We project 6.4% CAGR in India’s total trade through 2033, to $1.8 trillion annually, roughly in line with its high GDP growth. Among the drivers will be India’s growing popularity as a production base for companies seeking to diversify supply chains concentrated in China, hefty government incentives for manufacturing, a huge low-cost workforce, and rapidly improving infrastructure.

Geographically, India’s trade growth will be broadly based. Annual trade with the US is expected to more than double over the next decade, to $116 billion in 2033. This trend will reflect stronger political and economic ties between the world’s two biggest democracies, especially in areas like defense and technology. We forecast that India’s trade with the EU, ASEAN, and Africa will increase by around 80% over the next decade. It is projected to nearly double with Japan and Mercosur nations, and more than triple with Australia and South Korea. Trade with Russia is also projected to surge as India imports cut-rate Russian hydrocarbons.

The pace of India’s trade growth with China, while still strong, is expected to moderate. Among the reasons are India’s growing bilateral trade deficit with China, which has fueled economic unease in New Delhi. India is also becoming more skeptical of Chinese direct investment in its economy, particularly in sensitive sectors. This economic wariness is compounded by an ongoing border dispute between the two nations.

The EU’s Focus on Competitiveness

Geopolitical tensions, energy price security concerns, and a focus on values-based trade have impacted the 27-nation bloc’s future trade prospects. New barriers, such as the recently announced tariffs on imports of electric vehicles, are expected to cause trade with China to stagnate over the next decade. Trade with Russia, which has been heavily impacted by measures taken following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, is projected to decline by around $106 billion by 2033 if those measures remain in place.

Nevertheless, we project that total trade between the bloc and other nations will continue to grow by 2% annually through 2033. Annual trade with the US is expected to grow by $303 billion over the coming decade, largely driven by EU imports of US LNG, and accelerate with India, Turkey, and Africa. The EU’s recent deal with Mercosur, if enacted, would boost its trade with South America. We expect that Africa—especially North Africa—will become an important location for nearshoring manufacturing supply chains, with the continent as a whole becoming a greater source of the energy and minerals required for the green transition. We project that trade with India will grow 6% annually, led by the information technology, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing sectors. However, we expect that ASEAN will play less of a role in bolstering EU supply chain resilience than it will with North America.

These trends will have significant geopolitical implications, as noted in the recent report by the former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi. As a result, the EU will no longer be able to count on high levels of global trade growth or existing trading relationships. Deeper ties with emerging economies and a stronger EU internal market will also be important.

Five Imperatives for Thriving in a Changing World

To navigate geopolitical change and ensure business continuity, we recommend that business leaders take the following actions:

- Develop resilient and transparent supply chains. Companies should assess and diversify their sourcing strategies by extending their supplier base. They should deepen relationships with current key suppliers and prequalify additional ones. Firms should invest in supply-chain control towers that create transparency and monitor shocks in real time, making it easier to quickly adapt to disruptions. They should also consider optimizing product specifications and consider vertically integrating by producing more critical components in-house. Such efforts can ensure operational continuity and greater flexibility during geopolitical and supply-chain disruptions.

- Build geopolitical muscle. Enhance the organization’s ability to sense and respond to changing geopolitical landscapes. Strengthen decision-making processes to remain agile. Embed geopolitical scenarios and analysis into capital allocation and strategic planning so that the organization is flexible enough to be in position to manage risks and seize opportunities.

- Expand presence in growth markets. Prioritize high-growth regions in the Global South to capture emerging opportunities. A strong local presence in these markets will enhance competitiveness and help secure long-term growth.

- Embrace smart nearshoring. Companies should consider nearshoring strategies that provide low cost, a sound business climate, and resilience advantages. By relocating production closer to home markets, businesses can reduce transportation costs, lower their carbon footprints, and mitigate supply-chain risks. Smart nearshoring improves resilience and makes it easier to respond to shifting consumer demands and regulatory pressures in various regions.

- Invest in regional differentiation. As global trade fragments and regionalization accelerates, organizations will need to adopt differentiated structures and technology stacks. A one-size-fits-all approach will no longer suffice. Customizing approaches based on regional requirements will enhance agility, enabling businesses to stay competitive in an increasingly fragmented global market.

Geopolitics are steadily redrawing the map of global commerce. The ability to anticipate, analyze, and adapt to the geopolitical forces defining the future of trade will become an increasingly critical source of competitive advantage in the decade ahead.

About Our Research

This year’s trade model includes a number of improvements:

- Trade values are expressed in real 2010 US dollars to reduce year-to-year volatility.

- Enhanced AI and machine learning are used to create a more detailed model by tracking nine different macroeconomic variables over a 20-year period.

- Impacts of newly present influences, such as new trade agreements, trade wars, military conflicts and related sanctions, and climate-related trade policies, are captured on a case-by-case basis. Adjustments are applied to certain future forecasts.