For decades, the federal government and health insurers have focused on the needs of our aging population. Improving care for people in the Medicaid program is a perennial effort for states. Yet dual-eligible individuals, who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, have long fallen through the cracks.

Dual-eligible individuals have a disproportionate and growing impact on Medicare and Medicaid. Though dual eligibles make up 19% of Medicare and 13% of Medicaid enrollments, they account for 35% and 27% of the costs in these programs, respectively. This impact is only increasing. The number of dual eligibles is growing by 5% annually, and the cost to provide their care has slightly outpaced that. Complicated insurance and regulatory landscapes have hampered efforts to provide effective care for this population.

Improving care for dual eligibles can transform challenge into opportunity. New care models can deliver better outcomes and reduce costs for states and

payers.

We surveyed a nationally representative sample of enrollees and conducted interviews with dual eligibles, payers, and state Medicaid leaders to develop insights that can help payers and states better support dual-eligible individuals.

Dual Eligibles Have Varied and Nuanced Needs

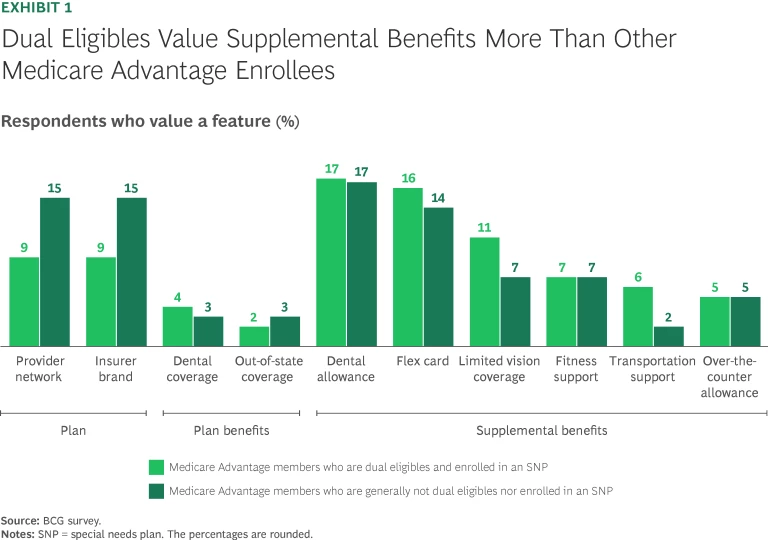

Dual eligibles are generally younger and have more financial challenges than individuals who qualify for only Medicare. Approximately 40% of dual-eligible individuals are under the age of 65 versus just 10% of all Medicare members, and to qualify for Medicaid, dual eligibles have a much lower average income. Such differences drive preferences. For example, dual eligibles are more interested than regular Medicare members in supplemental benefits—such as a flex card for grocery discounts and transportation support—that help with the costs of health-related social needs. (See Exhibit 1.)

The dual-eligible population is not homogenous and can be broadly segmented into two categories:

- High Level of Care. Dual eligibles who need extensive care are typically either younger, disabled individuals who require long-term supports or older, frail individuals with chronic conditions. In addition, individuals who require behavioral health care often fall into this category. An example of an individual who we interviewed in this category is Angie. At 30 years old, she is enrolled in Medicaid and qualifies for Medicare due to severe mental illness. She sees specialists for her physical and mental health and has been hospitalized. She also frequently sees other practitioners, including a dentist because she has lost her teeth.

- Low Level of Care. Dual eligibles who have few care needs are generally older individuals who have aged into Medicare and lack an extensive medical history or do not have long-term care needs. They typically need traditional care, such as that provided by primary care physicians. An example of an individual who we interviewed in this category is Jane, who is 82 years old and actively serving on the board of a community association for seniors. She is enrolled in Medicare and sees a primary care physician and some specialists, such as an ophthalmologist for cataracts. Jane values her grocery benefits and discounts for arthritis medicine.

Understanding these categories and requirements is important for states and payers to better meet their unique needs.

A Look at Care Models

Historically, Medicare and Medicaid have managed and paid for care for dual eligibles separately, without any coordination of care and benefits. This is still the predominant approach. The benefits for the majority of the 12.2 million dual-eligible individuals are currently administered through two plans—a traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage plan plus a Medicaid plan.

Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has encouraged a shift toward integrated care, where care across both Medicare and Medicaid is better coordinated and managed. While several types of dual eligible-specific plans now exist, they vary in their degree of integration (how tightly benefits and care across both programs are coordinated); fully integrated plans still cover just a small segment of dual-eligible individuals. (See the sidebar “Care Model Options.”)

Care Model Options

Regular Medicare plans with separate Medicaid plans cover more than half of dual eligibles (56%). These can be any combination of fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare or Medicare Advantage (MA) plans with separate FFS Medicaid or managed Medicaid plans.

Care models that are specifically for dual eligibles include the following:

- Coordination-Only Dual-Eligible Special Needs Plans (CO D-SNPs). Dual-eligible special needs plans (D-SNPs) are MA plans designed to cater to dual-eligible individuals. Twenty-three percent of dual eligibles are enrolled in CO D-SNPs. Most enrollment growth in plans focused on dual eligibles has been in this type. However, CO D-SNPs deliver little incremental value over two separate plans: they are simply required to inform Medicaid plans of hospital or nursing home admissions but have no other standard requirements beyond standard MA plans.

- Highly Integrated Dual Eligible (HIDE) SNPs. HIDE-SNPs require payers to offer both Medicare and Medicaid plans in a state, but do not require enrollment of dual eligibles across both plans. HIDE-SNPs are required to cover either behavioral health or long-term services and supports (LTSS). These plans have enrolled 14% of dual-eligible individuals.

- Fully Integrated Dual Eligible (FIDE) SNPs. FIDE-SNPs cover 3% of dual-eligible individuals and require them to be enrolled in a Medicare and Medicaid plan under the same payer, fully internalizing cost and enabling integrated and coordinated care. FIDE-SNPs also require the payer to cover LTSS and at least 180 days of nursing home care.

- Program of All-Inclusive Care of the Elderly (PACE). PACE plans cover 0.4% of dual-eligible individuals. These plans both finance and deliver individuals’ care generally through a community center. Not all dual eligibles qualify.

Federal demonstration plans called Medicare-Medicaid plans (MMPs) are being phased out in 2025. Many of the 3% of dual eligibles who were in these plans have transitioned to D-SNPs, and the remaining ones will do so this year.

Increasing the proportion of dual eligibles covered by plans that use integrated care models may deliver benefits to states, payers, and individuals. Studies have shown that integrated care models, such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Fully Integrated Dual-Eligible Special Needs Plans (FIDE-SNPs), may reduce institutional long-term nursing home stays, increase the use of home and community-based services, and improve patient satisfaction.

Regulatory Changes Are Driving Greater Integration

CMS has made several regulatory changes that aim to incentivize stakeholders to adopt integrated care models.

On January 1, 2025, these initial changes took effect:

- Enrollment periods for fully integrated care plans changed from quarterly to monthly to nudge dual eligibles to enroll in these plans.

- Medicare Advantage plans that are not dual-eligible special needs plans (D-SNPs) but that serve a large share of dual-eligible individuals (at least 70% for plan year 2025) will not be renewed by CMS, pushing payers to either change these plans to D-SNPs or fold them entirely.

By 2027, these additional changes are slated to take effect:

- New D-SNP enrollees must be enrolled in a Medicaid managed-care plan administered by the same payer, if available.

- D-SNP payers with Medicaid offerings will have to align their state service areas for Medicare and Medicaid to ensure dual eligibles can access all benefits in both programs. No more than one D-SNP per payer will be allowed in each service area, simplifying plan options.

States and payers will have to adapt, which may require rethinking their approach to dual eligibles.

Opportunities for States

Although dual eligibles account for 27% of Medicaid spending, many states have not prioritized devising or executing strategies for this population due to competing priorities or a lack of expertise. To improve care, states must ensure they have a plan focused on dual eligibles and dedicate capacity. Medicaid leaders have several strategic options to improve dual eligibles’ experience, boost outcomes, and potentially reduce long-term costs:

- Improve the integration of care. States could move from less integrated care models, such as coordination-only D-SNPs, to more-integrated models by selectively contracting with insurers. For example, states could contract only with D-SNPs that have an affiliated Medicaid plan or mandate that new D-SNP plans be highly integrated dual eligible (HIDE) or fully integrated dual eligible (FIDE) SNPs. Another option is to change requirements in the state Medicaid agency contract (SMAC). For example, states could mandate that D-SNPs payers train care coordinators in Medicaid benefits to help care navigation or that D-SNPs cover select Medicaid benefits.

- Improve care quality. Using the SMAC, states could introduce specific network requirements for D-SNPs such as specific types of care services, or states could require plans to report on specific metrics to boost transparency and oversight. States could also mandate D-SNPs to adhere to certain model of care requirements, for example, requiring care plans for members with certain needs or mandating primary care physician-to-enrollee ratios.

- Improve enrollment in integrated plans. States could use communication strategies to nudge or require dual-eligible individuals to move into integrated plans. For example, they could work with insurance brokers or self-publish materials to improve awareness. States could also change the enrollment process, introducing default or passive enrollment for integrated plans or incorporate mandatory enrollment in Medicaid managed care plans. (See the sidebar “How Different States Promote Integrated Care.”)

How Different States Promote Integrated Care

- Virginia requires exclusively aligned enrollment and asks that plans apply to CMS for default enrollment of dual eligibles into both managed Medicaid and a D-SNP under the same payer. New D-SNPs are only allowed if they also offer Medicaid managed care, and within the next two years, insurers that want to offer new managed Medicaid plans in the state will be required to offer a D-SNP.

- New Jersey has had FIDE-SNPs since 2012. The state requires SMAC recipients to have affiliated Medicaid plans. New Jersey relies heavily on communication to encourage enrollment, requiring reviews of marketing materials that payers provide to dual-eligible individuals.

- California requires D-SNPs to have an affiliated managed Medicaid plan in order to receive a SMAC. The state automatically enrolls dual eligibles in a managed Medicaid plan and D-SNP plan under the same payer and ensures that coordination protocols are outlined to support individuals who have particular challenges (such as dementia) or needs (such as community-based palliative care, for example).

Strategic planning should also consider timing. Choices around strategic options should be completed long before the contracting process for payers gets underway, particularly given the need to align Medicare and managed Medicaid for fully integrated care.

Many states have few resources dedicated to a dual-eligible strategy. To improve outcomes and reduce costs, states should consider increasing their resources and expertise to handle tasks such as insurer communication, data management, and contracting and enforcement.

Opportunities for Payers

With regulatory changes increasing integration, payers focused on dual eligibles should consider both how to win with enrollees and how to win as a partner with states, particularly as more insurers vie for Medicaid contracts.

To win with dual-eligible individuals, payers should take two steps:

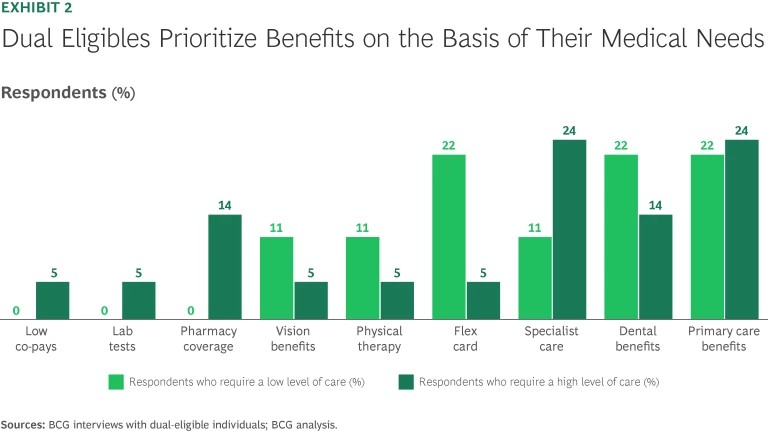

- Deliver the Benefits That Dual Eligibles Uniquely Want. Plans must be able to meet the needs of both groups of dual eligibles—those that require a high level of care and those that require a low level of care. (See Exhibit 2.) Given upcoming regulation limiting the number of D-SNPs to one per payer in each service area, insurers will have to balance table stakes benefits, such as groceries, with strong provider networks and quality providers.

- Create Market-Leading Integrated Medicare and Medicaid Experiences. Forty percent of the dual eligibles we interviewed who are in a D-SNP were considering switching insurers, and 50% were being advertised to daily or weekly about new plans. Almost every D-SNP plan examined changed their benefits year to year, offering increasingly generous supplemental benefits. Creating stickiness while avoiding competing over the generosity of supplemental benefits will require a market-leading experience. Integrating plans and providing a member experience—including a customer service experience—that feels unified and seamless is important. For example, 70% of dual eligibles who left their plans did so because of poor customer support, particularly their experience with the provider network.

To become a partner of choice with states, payers should ask themselves three key questions:

- What do states want from us? States are increasingly asking for higher-quality care models for dual eligibles, and they are giving preference to insurers that have expertise addressing the greatest needs (such as behavioral health) of their dual-eligible population. States also want longer-term partnerships with payers and for payers to have deep local knowledge and relationships.

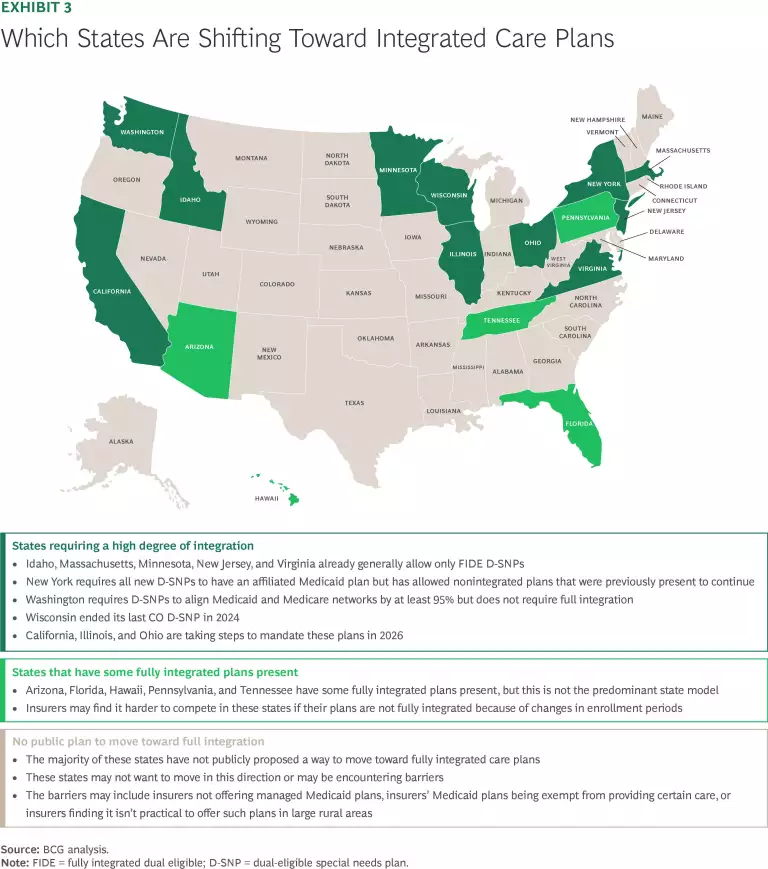

- What do we need to deliver to meet increasing requirements for integrated care? To win in states that are likely to prioritize integrated care, payers should build integrated offerings before regulatory changes kick in. (See Exhibit 3.) Taking this step includes developing an appropriate provider network (whether that be through payer acquisition or organic growth), devising clinical programs, and implementing underlying IT systems that facilitate integrated care for dual eligibles and a seamless experience for both members and providers.

- How do we set up our operating model to be more effective? Payers should consider how their operating model could better serve dual eligibles. For example, does the organization structure facilitate offering localized knowledge and support, and can the business units that serve dual eligibles align benefits, administration, and providers between the two programs. Payers should also consider how they organize and leverage data-driven insights, given that states want greater transparency and communication.

Now is the time for states and payers to focus on dual-eligible individuals. As the landscape shifts toward integrated care, getting this right can pay off. Significant savings can be achieved by payers and states by improving care models. But more importantly, outcomes can be improved for millions of dual-eligible individuals who are often highly vulnerable and who deserve care that meets their unique needs.

The authors thank Jennifer Labs for her contribution to this article.