Nations increasingly vie for leadership in global trade , foreign direct investment , and AI—but they do not yet compete as openly for the world’s best and brightest talent . We think that’s bound to change, despite growing discontent among voters about immigration and the rise of populism.

In the past few years, nations have been pursuing immigration policies designed to attract highly skilled talent not just for economic growth but to build two other foundations of geostrategic advantage. First, foreign workers with advanced skills can boost entrepreneurship, innovation, and resilience in key industries such as semiconductors, AI , green energy, fusion, and robotics—sectors that are all critical for maintaining global influence. And second, high-net-worth and other top taxpayers from abroad can strengthen a nation’s fiscal capacity for public investments. A recent BCG analysis shows that highly skilled immigrants can deliver upwards of $1 million in lifetime net fiscal benefits for their host countries.

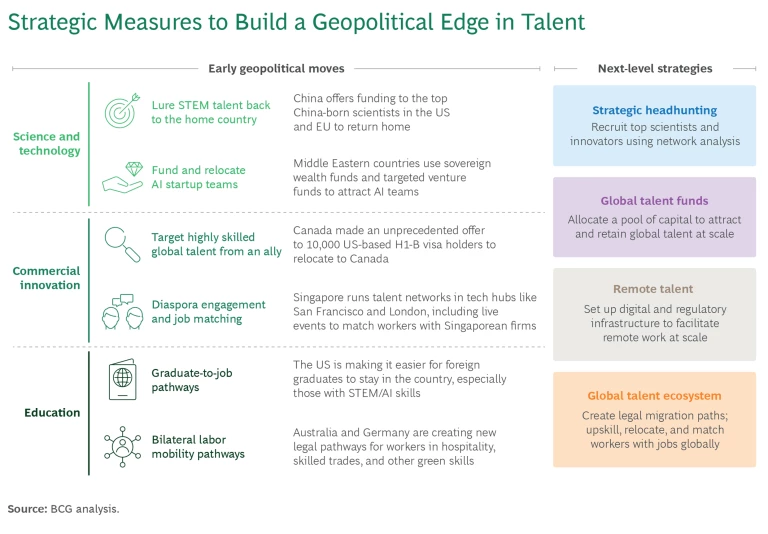

Achieving a meaningful geopolitical edge in talent requires bold, novel, and strategic measures. Most countries, however, remain focused on incremental, tactical approaches to harnessing global talent—partly because of populist headwinds and partly because of uncertainty regarding the optimal design of immigration policies that will attract the needed talent. But early signs suggest that competition for highly skilled workers is beginning to shift into the geopolitical sphere.

Historical Precedents—and a New Sense of Urgency

The idea that geopolitical competition can extend to talent is not new. As early as the 17th century, the state of Prussia actively sought to attract highly skilled workers from France, Switzerland, and Austria to bolster its fiscal capacity and invigorate its economy. Over time, these efforts evolved into sophisticated recruitment programs aimed at drawing foreign workers with specialized skills—such as in glass manufacturing and locomotive engineering—that were scarce in Prussia.

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

More recently, Canada announced a tech talent strategy in 2023 to lure 10,000 highly skilled global IT workers from the US to Canada. The program was heavily oversubscribed after just a few days, and so far more than 1,000 applicants are in the process of leaving the US and moving to Canada.

What has changed is the increased urgency to encourage highly skilled workers to immigrate. But there’s a silver lining to this development. A new geopolitics of talent could focus scarce political capital on a critical area—immigration reform—where meaningful progress is needed but likely will not happen without broad-based political cooperation. The recent re-shoring of semiconductor manufacturing to the US and Europe is a prime example of how geopolitical concerns can push through previously stalled initiatives.

Early signs suggest that competition for highly skilled workers is beginning to shift into the geopolitical sphere.

Similarly, although many Americans are weary of illegal immigration, eight out of ten support immigration reform that favors people with in-demand skills, according to the Pew Research Center. While too early to tell, a second Trump administration could crack down on illegal immigration while introducing a merit-based system for highly skilled talent. Meanwhile, Japan and many European and Middle Eastern countries are interested in opening their borders to skilled immigrants, but their efforts are often bottlenecked by bureaucratic red tape.

Competition for Talent in Three Areas

The geopolitical competition for talent is primarily playing out across three domains: science and technology, commercial innovation, and education.

Science and Technology. Some countries already use targeted programs to attract science and technology talent, such as scientist repatriation initiatives or schemes that help recruit in-demand talent for technology firms. China’s Thousand Talents Plan, for example, which launched in 2008, aims to bring home Chinese-born workers in science and technology in order to boost innovation and strengthen the nation’s global competitiveness. The program has already led to advancements in key fields such as AI and biotech. Like many such repatriation programs, however, it has faced criticism—particularly from the US—over intellectual property concerns.

In AI and fusion energy, countries aggressively court not just leading scientists and other talent but entire startups. AI companies in the EU and the UK, such as Aleph Alpha, Synthesia, and Stability AI, have been approached by rival nations with generous offers, including subsidies, tax breaks, and lighter regulation. Exemplifying Europe’s relative weakness in scaling deep-tech startups, German nuclear fusion startup Marvel Fusion will build its first demonstration facility in the US, in partnership with Colorado State University, in order to comply with the conditions of a term sheet that require the company to build the plant in the US.

Commercial Innovation. In the domain of commercializing innovation, we see well-established tactical initiatives by many nations—and the potential to attract talent more strategically.

Many countries already run diaspora engagement initiatives aimed at connecting with their compatriots in other countries. For example, Singapore fosters technology networks in San Francisco, London, and New York. The country also invests in digital networking tools and runs global events that bring together Singaporean talent abroad with domestic firms seeking to hire experienced workers.

In parallel, Singapore is investing in major digital upskilling investments for its own domestic labor force. The goal is to accelerate the adoption of productivity-enhancing digital technologies among midcareer workers and—where possible—to introduce robotics and AI to further increase productivity.

The geopolitical competition for talent is primarily playing out across three domains: science and technology, commercial innovation, and education.

Other countries have ambitious schemes to attract highly skilled, often digital, talent from abroad. The European Union runs one of the largest and most generous programs, the EU Blue Card, which provides an unlimited number of work visas for highly skilled university graduates, provided they have a job offer and meet a relatively low salary threshold. (In Germany, for example, the threshold is roughly 1.5 times the per-capita income, and the salary requirement is even lower for workers with digital skills.) Although the Blue Card program has some administrative barriers, it is more open and welcoming than programs in other countries or regions, which offer only a fixed number of slots per year or impose significantly higher income hurdles.

Education. Countries also seek a geopolitical edge by attracting students and researchers to their universities. To some extent, they have always done this. For example, Germany runs one of the largest scholarship programs aimed at fostering international research, funding grants for about 145,000 students and researchers from 200 countries each year. The program is a key part of Germany’s projection of soft power and was recently used to bring promising Afghan students, many of them women at risk, to Germany.

Similarly, the US recently started removing some administrative hurdles for foreign students, clarifying previously ambiguous rules so that exceptional foreign graduates can acquire work visas or permanent residency more easily. As a result, the number of foreign students graduating from US universities and granted an O-1A work visa or employment-based permanent residency was near an all-time high as of 2023. At the state level, a number of local private-sector initiatives are under way to systematically link universities with immigration support and local employers.

A more straightforward next step would be legislation that offers permanent residency—with appropriate safeguards—to university graduates in fields such as semiconductors, AI,

clean energy

, and other STEM disciplines. In the long term, however, this approach may not be sufficient, as other nations would likely respond with their own measures, further enticing talent to move (or stay) there.

Four Next-Level Strategies

In all three realms of science and technology, commercial innovation, and education, some countries have geopolitically motivated policy initiatives in place—but they could do far more. Moving beyond these policies would require a greater degree of strategic intent and technological sophistication. We offer four scalable, next-level strategies. (See the exhibit.)

Headhunt using network-based recruiting. Countries can systematically identify and recruit high-value scientific and technological talent from nonaligned nation-states. The analytical toolbox and datasets required to do so already exist. Governments could use network analysis of patents, scientific literature, open-source information, or professional communities to identify “nodes”— individuals or organizations that are instrumental in the flow of information, resources, or influence across their respective areas of research—and use this information for targeted recruiting campaigns.

Create talent funds. Another highly promising option is talent funds , pools of capital intended to attract and/or retain specific types of highly skilled talent. They are typically funded by a government entity (for example, a labor ministry or state-level economic development agency) or by the private sector (such as a chamber of commerce or philanthropist). Talent funds operate in a similar manner to sovereign wealth funds but are at a much earlier stage of development; some exist on a small scale in a few cities, but most have not yet been scaled up. They feature a high return on public investment and complement existing workforce development efforts by incentivizing talent relocation, upskilling, and job placement.

Develop a remote option. Remote work allows firms to access global talent without physically relocating people, mitigating immigration challenges. While innovation-intensive work often requires co-location, and some people want to relocate in order to gain better pay or services, a growing number prefer remote work. To support this option, nations must enhance their digital infrastructure, simplify cross-border work regulations, and help firms tap into remote talent more seamlessly—for example, through incentives or upskilling programs that promote innovation more broadly.

Build global talent ecosystems. Countries with either a surplus or a dearth of talent can share training and certification programs, with the goal of educating workers for local and global labor markets. Some European, African, and Asian countries currently operate such ecosystems. When designed well, these programs—also called global skill partnerships—can help emerging economies gain access to technology and educational resources—such as in green skills—while improving job opportunities for local workers.

Increasingly, emerging nations see the emigration of talent not as a loss, but as an opportunity to access remittances and global labor market opportunities for their citizens—and to build deeper ties with geopolitical allies. In areas of conflict such as Ukraine, Lebanon, and Syria, a diaspora of skilled emigrants is a valuable latent asset.

As the race for top talent intensifies, nations that take a strategic, forward-looking approach will secure a lasting advantage. Although some are already deploying tactical initiatives, such as targeted recruitment programs and diaspora engagement, and are gradually opening their borders to highly skilled talent, there are opportunities to make these efforts more strategic. Countries that are first to adopt network-based recruiting or to establish dedicated talent funds, along with other transformative approaches, will enhance their competitiveness in key geopolitical areas and boost their fiscal strength.

At the same time, firms operating in the geopolitical arena should make their voices heard. Their active participation can shape and influence these emerging strategies, ensuring alignment with real-world needs and opportunities. By engaging with governments and other stakeholders, companies can help turn tactical talent initiatives into enduring solutions.

Ultimately, the competition for talent is as much about attraction as it is about retention of highly skilled talent—local and global. A credible strategy to attract the best and brightest globally requires solid political support. That starts with improving the conditions for all citizens to thrive.