This is a follow-up article to “Upstream Energy Companies Cut Costs. Can They Sustain the Results?” published in June 2024.

Optimizing production from existing oil and gas wells may represent the industry’s best opportunity in the near to medium term to crack the energy trilemma: meeting the world’s energy needs at the most affordable cost with a minimum of carbon emissions. Tapping into reservoirs of underproduced barrels adds substantial volume at a financial and carbon cost that can compete with, and even beat, new projects in frontier areas. Considering that various estimates put proven global reserves at around 1.7 trillion barrels, and that the current average ultimate recovery rate is 20% to 40% for oil and 60% to 80% for gas, the potential opportunity is enormous.

To be sure, there are tall barriers to increasing production efficiency, as any petroleum engineer knows. But given the maturity of global energy resources and the difficulty, risk, and expense of new exploration efforts, production optimization can be a huge value driver for traditional energy companies. Here’s why it is worth “exploring.”

Cost, Carbon, and Value

Our work with clients, including integrated oil and gas companies, independents, and national energy companies, has spotlighted three distinct aspects of the production optimization opportunity.

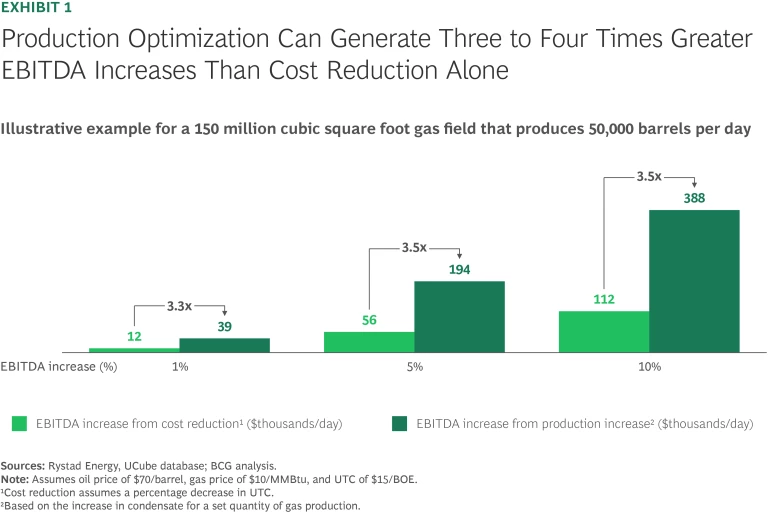

Biggest Bang for the Buck. Production optimization is the cheapest way of adding barrels. It can deliver a much bigger boost to EBITDA than cost improvement measures alone. Our analysis shows that a dollar invested in production enhancement will deliver three to four times more payback than cost measures. (See Exhibit 1.) It’s also much cheaper than new exploration. The North Sea Transition Authority recently reported that the average cost of well intervention for increased recovery is £12 per barrel of oil equivalent (BOE) in the North Sea, while the cost to find and develop new reserves is over 1.75 times higher—more than £20/BOE in the same basin.

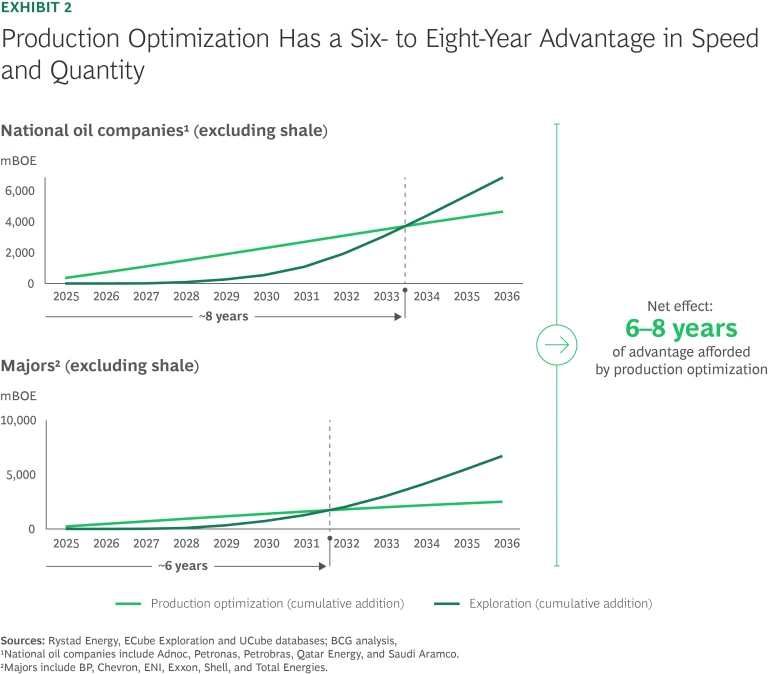

Making Up for Subpar Exploration Results. Exploration investment—and, more important, exploration success—have been at all-time lows in recent years. In some brownfield basins, there is simply not much scope for further exploration. In other areas, political, regulatory, or tax regimes are hurdles to further exploration investment. Enhancing existing production can help companies meet investor expectations for exploration and production operations without relying solely on acquisitions and exploration initiatives (though a mix of all strategies will be required). A 5% increase in the daily production of existing fields (excluding unconventional resources) from now until 2030 is worth about $600 billion in additional revenues for the industry. Production optimization delivers more daily barrels, sooner. (See Exhibit 2.) Because of the slow start for new exploration activities, total additional production takes six to eight years to catch up, affording companies greater flexibility in their capital allocation decisions.

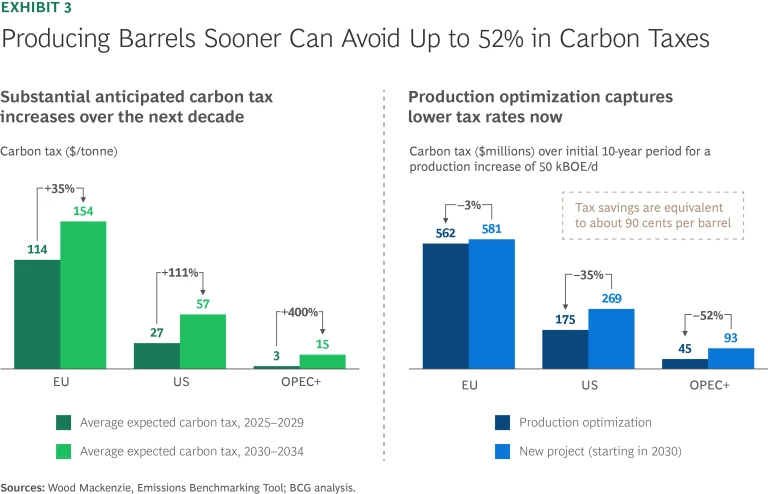

The Lowest-Carbon Barrel. Optimizing production offers a lower-carbon alternative to developing new fields and may also come with tax advantages in some jurisdictions. New field development is less carbon intensive on a per unit basis, and new fields typically operate at about 28% lower CO₂ intensity. But production optimization reduces the carbon intensity of scope 1 and 2 emissions by 10% or more because the essential infrastructure is already in place. The estimated emissions from the material production, fabrication, transportation, and installation of one new floating production storage and offloading facility producing at 50,000 BOE (50 kBOE) per day (18,250 kBOE per year) is about 185,000 tonnes CO2e. The crossover point for a new field’s lower intensity is one to two years, a significant period if the production and price horizon is uncertain. Production optimization can offer a better near‐term path for CO₂ and capex savings.

In addition, production optimization can yield as much as 52% in carbon tax savings over new projects. (See Exhibit 3.) This is equivalent to almost $1 per barrel.

Overcoming the Typical Barriers

Despite the clear benefits, production optimization remains an underleveraged strategy. One reason is that energy companies tend to focus first on costs, where they have lots of experience and are good at coming up with short-term—and high-potential—answers. But cost cutting does not increase reserves or revenues, and to boost production, operators typically focus on new drilling. Extracting more oil and gas from current reservoirs has received less attention and generally requires overcoming endemic structural and technical challenges.

That said, major energy companies today have or can access the resources they need to blow through the barriers to adoption. A combination of advanced technologies, improved data utilization, and an adaptable operational strategy and organization can both accelerate the rate of production and increase the estimated ultimate recovery from wells and fields. A production optimization orientation adjusts processes and ways of working and brings advanced technologies such as AI to bear on the tough technical challenges, enabling producers to overcome the barriers to greater recovery.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on energy

Minimizing Subsurface Issues. The biggest geological impediment to greater field drainage typically is reservoir compartmentalization, the assessment of which requires detailed pressure monitoring in wells and precise seismic mapping of reservoir features. Both can now be done by reprocessing legacy seismic data or acquiring new data to locate bypassed hydrocarbons and identify ideal access and drainage solutions (such as enhanced recovery mechanisms using water or chemical flooding, pressure maintenance, or infill drilling). AI workflows that are trained to answer field-specific questions can interpret the enormous data sets associated with field modeling studies. Forward modeling of various intervention options helps in determining the best commercial and technical outcome. Advanced technologies not only accelerate production, they also tap into otherwise untouched resources and add to the ultimate recovery.

Improving Well and Reservoir Management. Each of the many issues affecting well performance (such as clogging, corrosion of materials, wax deposits and scaling, and production of water, unintended gas or oil, or sand) requires its own preventive or treatment measures. Measurement, monitoring, modeling, and planning ahead can help. For example, pressure maintenance and AI-assisted well-by-well rate management can prevent premature water or gas breakthrough. Appropriate lifting techniques can address liquid loading in wells. A good understanding of geomechanics, liquid properties, and fluid dynamics aids in the prevention and treatment of sand production, wax deposits, and slugging in wells, facilities, and pipelines. Newer techniques leverage rigless methods such as vessel-based well interventions that help manage costs. Ideally, these procedures are coordinated—or at least not undertaken in isolation.

A production optimization orientation adjusts processes and ways of working and brings advanced technologies such as AI to bear on the tough technical challenges.

Boosting Facility and Pipeline Performance. Longer asset lifespans or inadequate maintenance are often the root causes of underperformance, undermining both production rates and cash flows. These issues are essential to address when it comes to reducing losses and improving uptime. The most effective improvements are made in the design phase or during major maintenance events. Engineering upgrades, such as a transition to modular facilities, can improve stability and isolate failure points. Active monitoring and predictive maintenance (aided by daily loss management workflows with AI-assisted root cause analysis) will lead to fewer maintenance visits, more stable operations and, potentially, execution of rate-additive measures.

Removing Organizational and Information Constraints. Optimizing asset performance is not only a technical issue, it also requires an efficient, cross-functional, and well-informed organization. Data from the subsurface and from wells and facilities is often imperfect, especially in the case of older assets with inadequate sensors and testing systems. Compounding this problem, the data often resides in different systems or functions. Instead of seeing a (mostly) full picture, employees work in silos with incomplete data access and often different incentives, which can lead to a lack coordination and focus. One common example: subsurface resources are focused on maximizing lifetime value from new drilling rather than delivering incremental value in the current year by identifying and prioritizing well interventions. To address such issues, teams need to be aligned on common goals with ready access to supporting data.

Overcoming Commercial and External Constraints. Factors external to the producing asset itself can affect performance. For example, reduced demand, which can occur because of export restrictions or customer capacity limitations, may curtail production and introduce inefficiencies. Or weather events, such as hurricanes, can prevent access to platforms and postpone work. Exploring ways to limit or remove such constraints—for example, by renegotiating a commercial delivery schedule or using predictive data and dynamic planning and scheduling—can help prevent potential production from going unrealized.

How Two Companies Optimized Production

Our experience—which includes helping operators achieve increases of 2% to 5% in their production rates from optimization programs—shows that companies need to align workflows to a “chase the barrel” outcome and equip themselves to make decisions driven by the best available data. Here’s how two different types of companies benefited from these moves.

Integrated Operator. A large operator with a mix of more than 1,000 onshore and offshore wells in a mature basin faced declining production and a doubling of unit operating costs over the last decade. With limited further greenfield growth potential, production optimization became the critical lever to managing the decline, extending asset life, and controlling unit costs. The approach targeted frontline challenges around informational and organizational silos with the goals of improving the volume and quality of available opportunities, sharpening the production optimization workflow, and combining the right capabilities to go after more barrels. The company was able to achieve a 6% production gain in one cluster of the field, amounting to $30 million per year, with full potential of more than $200 million per year at scale.

Companies need to align workflows to a “chase the barrel” outcome and equip themselves to make decisions driven by the best available data.

Several aspects of the optimization program helped overcome barriers such as those described in the previous section. An improved focus on and appreciation for surveillance and dynamic models helped close some of the data gaps in reservoir and well reviews. Redirecting subsurface capability away from low-probability new projects toward near-term production optimization accelerated production, cutting time to maturity from months to weeks. This was enabled in part by comparing the impact of all potential interventions across commercial, facilities, wells, and reservoir domains, allowing a “fair fight” among alternatives. Improved data quality and work execution helped leadership adjust the company’s risk appetite by showing the benefits of taking calculated risks to increase production, rather than maintaining the traditional focus on threat mitigation.

Onshore Operator. An operator with more than 350 midlife gas and condensate wells wanted to improve the ratio of condensate relative to gas (and water) within the existing infrastructure to take advantage of higher unit prices for condensate. The key challenges were production flow conditions and the absence of real-time data, which inhibited coordinated, timely, and effective action by well and operational teams.

The application of digital and AI technologies enabled better visibility into the causes and effects of actual (as opposed to theoretical) operating conditions with respect to production flow—such as bottom hole pressure, tubing head pressure, and well-to-well back pressures—given historical data and ultimately real-time current data. As a result, the company was able to optimize for condensate volume. For example, thanks to a better understanding of the correlation between higher levels of liquid load in the separator and lower condensate volume, the operator could adjust the liquid load and well choke settings to improve output. AI enabled the system to learn using both historical and real-time data to modify its recommendations, ensuring that the most accurate and lowest-risk decisions were implemented. The company achieved optimization potential of more than 5%, with a scaled-up value of more than $100 million per year. The new tool provided a real-time “single source of truth” for the operations and well and reservoir management teams, allowing them to streamline their barrel-chasing processes and communications and achieve a higher degree of coordination and collaboration.

They say you can’t cut your way to growth. But exploration and production operators can optimize their way to increased production and higher EBITDA. Companies that embed production optimization capabilities will also gain an edge in reserve longevity and financial returns while reducing their emissions intensity.

The authors are grateful to Alex de Mur, Michael Buffet, and Uday Singh for their contributions to this article.