The downtown has been declared dead—a victim of COVID. Fewer people are frequenting restaurants and retail spaces in the city center, and more are spending in the suburbs. According to research from third-quarter 2023 covering 118 major cities in 50 countries, suburban spending has grown 15 percentage points more than that of downtown areas (the so-called doughnut effect).

But our research suggests a different narrative: the world’s cities have arrived at a moment of reinvention and revival. It’s true that the city center is struggling, which our analysis of 38 CBDs and 13 of the world’s largest and wealthiest megacities confirms. We also identified several exceptions, however, with Tokyo the most notable. Already a model of urban innovation, the world’s largest city—home to more than 37 million people—has figured out how to adapt to new working norms.

The world’s cities have arrived at a moment of reinvention and revival.

In Tokyo, the CBD—traditionally a center for offices with large numbers of workers commuting from far-flung locations—is being transformed into what we call a knowledge campus. This new type of CBD

attracts both businesses and talent,

offering opportunity and optionality, and satisfying a wide cross-section of needs: company leaders who want to enhance productivity, employees who want opportunity for social interaction, commercial developers that want to keep their buildings filled with tenants and charge competitive rent, and cities that want to attract businesses and boost the tax base. In the future, even the office itself will be a microcosm of the CBD.

The Decline of the Central Business District

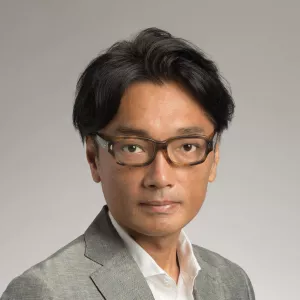

Our CBD study assessed commercial vacancy rates and rent, and found that in many CBDs, developers have been hit hard, facing rising vacancies. Declining commercial rent is also commonplace, an indicator of developers’ negative expectations regarding the future of the market. Of the 13 cities in this analysis, 3 stood out for their comparatively strong progress. Tokyo and Osaka, Japan, as well as Seoul, South Korea, achieved positive outcomes on vacancy and rent metrics and performed strong financially overall. (See Exhibit 1.)

The otherwise negative picture reflects the impact of COVID, which has been felt deeply in the CBDs that have long been home to white-collar jobs—and thus the source of cities’ economic and cultural vitality. (See “Defining the Central Business District.”)

Defining the Central Business District

A CBD, for our purposes, can be defined as the geographic center of business activity in a city, characterized by:

- Substantial Size. It features a concentration of business activities within a radius of 1 kilometer.

- Notable Economic Scale. The net added value or gross regional product of the district must account for at least 2.5% of the total economic scale of the metropolitan area.

- High Building Density. The district must have a floor area ratio (FAR) of 4 or higher, comprising medium- to high-rise buildings, generally averaging four to eight stories (or more).

A 2023 study on pandemic recovery in North American cities found that foot traffic in roughly half of the 62 cities surveyed remains below 50% of prepandemic levels, and only 4 of those cities have fully recovered their bustle.

The negative outlook for CBDs can create a vicious cycle: reduced activity in CBDs translates to lower tax revenues, which leads to decreased funding for area upkeep, which further diminishes the CBD’s attractiveness. Long-term consequences could include significant depopulation of city centers. But this trajectory isn’t a foregone conclusion.

New norms for white-collar work are changing the world’s cities. On any given day, people may be logged on at home, a coworking location, a coffee shop, or their company’s headquarters. In most cities, this experience is uneven at best; for many employees, it involves a series of disjointed transitions between systems and spaces. There’s a clear opportunity for companies and developers to fix this problem—which is what we observe happening in Tokyo.

Five Factors Driving Tokyo’s Urban Resilience and Innovation

Tokyo is not only the most populous and wealthiest city in the world but also a vibrant cultural hub topping many livability indicators, such as the number of restaurants, museums, and other cultural amenities. In terms of economic efficiency, Tokyo CBDs outperform those in most megacities thanks to a combination of low vacancy rates, growing office supply, and minimal declines in rental rates.

Tokyo’s success is no accident—it is the result of innovative urban planning and development practices. The city has consistently set the blueprint for hyper-connected, high-density infrastructure, inspiring urban-planning strategies around the globe.

Tokyo’s success is no accident—it is the result of innovative urban planning and development practices.

Among Tokyo’s most celebrated urban-planning achievements are its century-old commitment to transit-oriented development (TOD)—which enabled the city to move well ahead of other megacities in shifting from car dependency to rail-based commuting—and its strategic relaxation of floor area ratio (FAR) regulations that determine allowable building size relative to land area in order to guide housing development. In particular, Tokyo provided FAR incentives for developments that included residential components, especially high-rise housing in central areas. This approach significantly increased housing supply while curbing sharp rises in property prices. For instance, despite substantial population growth in Minato Ward, housing prices rose by only about 45% over two decades—a modest increase compared with San Francisco’s 231% surge under similar demographic pressure.

We studied five major central Tokyo CBDs—Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, Roppongi, Shibuya, Shinagawa, and Shinjuku—and found that five key factors drive their success.

Density Done Right. All five central Tokyo CBDs are not only compact but are among the most intensely used urban spaces globally. While every city center is denser than its surroundings, Tokyo CBDs stand out for their hyper-density, balancing high employment concentration with diverse urban functions.

The central part of Tokyo significantly exceeds the density of CBDs in other megacities. Tokyo has a population density of more than 70,000 people per square kilometer, compared with approximately 35,000 in Manhattan and around 17,000 in both inner London and Paris (all figures represent daytime population

BCG Henderson Institute Newsletter: Insights that are shaping business thinking.

The five Tokyo CBDs are also inherently designed as walkable areas with seamless access to essential, lifestyle, and premium amenities—from public transport and health care to fine dining, luxury retail, and cultural institutions. The multifunction density sustains economic and social vibrancy during and beyond office hours by enabling planned and spontaneous interactions. This feature sets Tokyo CBDs apart from other economically successful sectoral clusters like Silicon Valley or Boston’s Route 128.

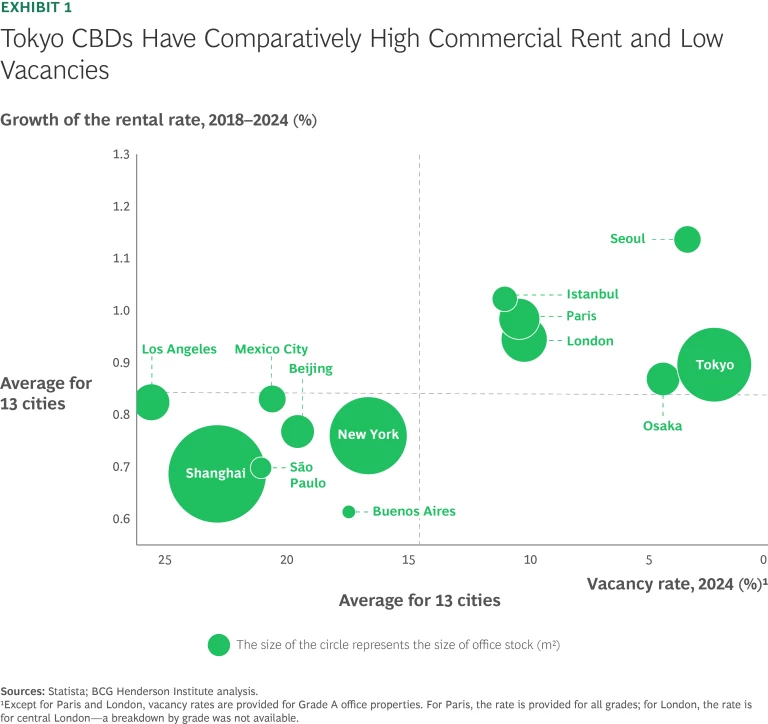

Superior Transportation and Connectivity. As the largest city in the world, Tokyo naturally deals with the challenges of congestion and the resulting effect on commuting time. But statistics show that Tokyo residents, on average, spend roughly the same amount of time commuting as do those in cities like Paris, London, and New York—and significantly less than people in cities with the longest commuting times, such as Istanbul or São Paulo.

Tokyo looks even more impressive when we adjust the commuting-time figures to account for the city’s size and population. For example, after this area adjustment, Tokyo has the second-lowest commuting time among the 13 cities we studied. We used three additional coefficients: the size of the area divided by commuting time (the higher, the better), number of passengers using the subway per year relative to the urban population (the higher, the better), and density-to-commuting-time coefficient (the lower, the better). These provide a more accurate assessment of the transportation system’s efficiency, taking the city’s size into account. (See Exhibit 2.)

What is the secret? All five Tokyo CBDs are located at major public transportation hubs, each within a roughly 1-kilometer radius from its central station. This compact scale ensures that most office buildings are only a few minutes’ walk from the nearest station. Additionally, many stations are connected directly to office buildings via extensive underground pedestrian networks, shielding commuters from wind, rain, and extreme heat.

Almost all workers access Tokyo CBDs via public transportation, primarily rail, benefiting from one of the world’s most extensive and efficient transit systems. With high-frequency train services and seamless connections between lines, commuting to and within Tokyo CBDs is remarkably smooth. This well-integrated transport infrastructure, along with enhancements such as transit terminals, expanded pedestrian networks, and commercial facilities within stations, makes Tokyo CBDs more convenient and accessible compared with other global business districts.

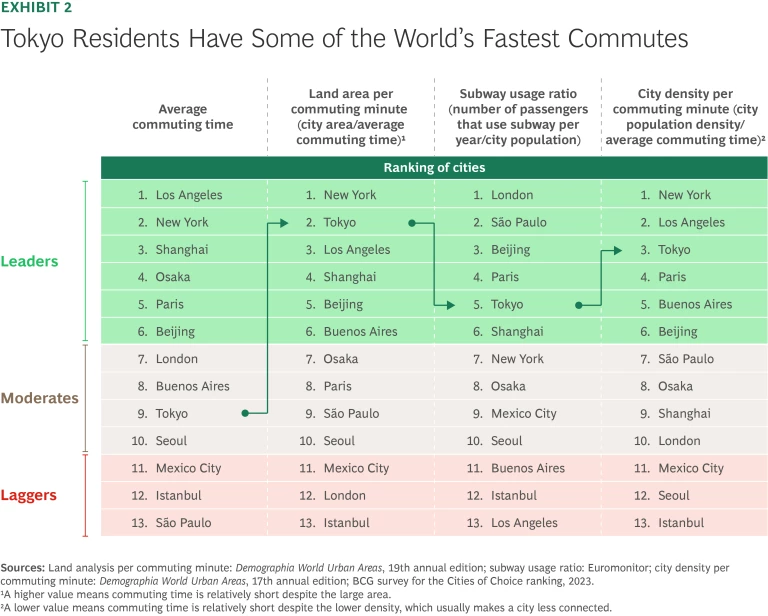

An Elevated Mixed-Use Approach. Unlike most CBDs in other cities we analyzed, Tokyo CBDs display a remarkable diversity in land use. For one, they are not dominated by office spaces; instead, significant portions are allocated to commercial use, residential properties, green spaces, and other public areas. For instance, the share of office spaces in Tokyo’s core CBDs ranges from 26% to 38%. The sole exception is Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, where office properties slightly exceed 50%. In contrast, well-known CBDs in other cities dedicate more than 60% of their area to office spaces. For example, Paris’s La Défense reaches almost 70% and London’s Canary Wharf exceeds 80%. (See Exhibit 3.)

Moreover, Tokyo CBDs have carved out a notable amount of space for residential properties. In Roppongi, for example, residential spaces make up nearly 25% of the total area, offering a stark contrast to office-dominated districts in other global cities (where residential space typically does not exceed 15% to 18%). The presence of housing in CBDs ensures that essential services, dining, and entertainment are readily available, enhancing overall livability. Unlike traditional business districts, which become deserted after working hours, Tokyo CBDs continue to see foot traffic in the evenings and on weekends, supporting local businesses and contributing to a safer, more dynamic urban environment.

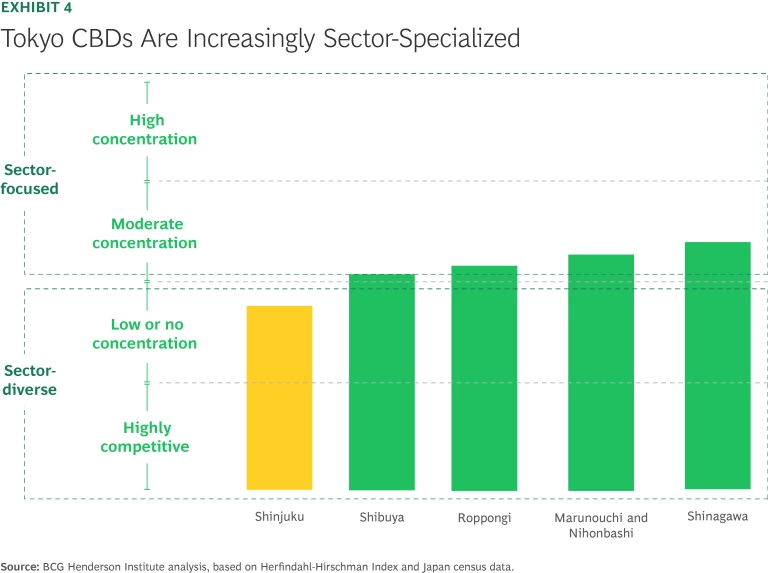

A Sectoral Focus. Most Tokyo CBDs feature sectoral specialization, which marks a shift for the city: historically, its CBDs featured a more uniform mix of corporate headquarters, government offices, and conventional financial institutions. Roppongi has emerged as an international tech-driven district, while Marunouchi and Nihonbashi have further sharpened their specialization in finance and professional services. Shibuya stands out for its strong presence of digital creative industries, and Shinagawa is increasingly characterized by growing concentrations of IT as well as wholesale and retail trade activities.

To quantify the diversity of sector representation across these CBDs, we used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure commonly applied in market concentration analysis. The index calculates the sum of the squared market shares of each industry within a given area. A lower HHI indicates a more diverse sectoral composition, while a higher HHI signifies industry concentration. Generally, a market—or in this case, a CBD—is considered diverse if the index falls below 1,500 and concentrated if it reaches 1,500 or higher.

Using this measure, four of the five major CBDs in central Tokyo can be classified as sector-focused, meaning they have a strong concentration in specific industries. The only exception is Shinjuku, with its more balanced mix of industries. The two most sector-concentrated CBDs are Shinagawa and Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, where a few dominant industries shape the economic landscape. (See Exhibit 4.)

CBDs with sector specialization create a win-win: tenants gain local scale and command global credibility and influence in their respective sectors, while workers have an opportunity for serendipitous interactions with peers—leading to better innovation—as well as more options in their career paths.

Unique Character. In the context of cities, character includes both tangible elements, such as architecture, design, and types of restaurants and shops, as well as intangible elements, like atmosphere and events.

In Tokyo, a CBD’s character often depends on the sector it houses. Roppongi, an IT hub, features a modern design that seamlessly blends high-tech architecture with nature-inspired elements. Green spaces bump up against cutting-edge structures. The Shibuya district, a digital and creative cluster, has a dynamic streetscape with vibrant architecture and an eclectic mix of colors and forms. It blends bold, avant-garde architecture, neon-lit streets, and a diverse collection of commercial and cultural spaces. In contrast, Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, home to major banks and professional service firms, present a more formal appearance—harmonizing modern skyscrapers with well-preserved historic architecture.

These differences in architectural and spatial design are further highlighted by a distinct variation in amenities. While the prestigious Marunouchi and Nihonbashi district—populated with bankers and strategic consultants—also boasts the most luxurious hotels and well-established high-end brands, the ever-vibrant Shibuya thrives as a hub for cutting-edge fashion boutiques, innovative pop-up experiences, clubs, bars, and live-music venues.

There is a clear connection between CBDs’ character and the talent they attract. Central Tokyo developers focused on addressing the individual preferences of the people working there, rather than just the needs of corporations. It is an ongoing process; in our interviews with key developers, they tell us they continually fine-tune CBDs to meet evolving requirements. The vibrant, dynamic, and chaotic Shibuya targets the creative class, while the more bourgeois Marunouchi and Nihonbashi cater to professionals in finance and strategy consulting.

There is a clear connection between CBDs’ character and the talent they attract.

Corporations have come to appreciate this approach. Google faced a tough decision when choosing the location for its new Japanese headquarters, debating between Roppongi and Shibuya. Ultimately, the company settled on Shibuya, drawn by the district’s vibrant creative atmosphere, which aligned with the values and mindset of its employees.

The Rise of the “Knowledge Campus”

When considered together, the five factors above start to resemble a university campus, which provides integrated spaces for both work and life within tightly knit communities of professionals. Clustered together on campuses, professors and students can seamlessly continue their intellectual exchange beyond the confines of laboratories and lecture halls, effectively blurring the distinction between work and leisure time.

A case in point: when Francis Crick and James Watson announced their groundbreaking discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953, they didn’t do it from the lab where they worked at Cambridge University. They went nearby to The Eagle pub, knowing it was a popular gathering spot for fellow scientists and researchers.

Similarly, the burgeoning CBD model in Tokyo can be characterized as a knowledge campus. By bringing together employees from the same sectors and fostering interactions beyond office walls, these campuses enhance the exchange of ideas—a critical driver of productivity in the knowledge economy.

The idea that sector specialization increases productivity is not new—it was first introduced by Alfred Marshall in the late 19th century and later expanded by Michael Porter in the early 1990s. Recent research on productivity emphasizes that higher efficiency is not merely a result of corporate proximity but rather the enhanced interactions among talented individuals, which encourage knowledge spillovers.

Numerous data-driven studies support this insight. For example, a 2024 study examined the role of collaboration in scientific productivity by analyzing the networks of Nobel laureates. According to a June 2024 article in Scientometrics, the research found that collaborative efforts significantly contribute to scientific innovation and productivity, underscoring the importance of interactions among skilled professionals in generating knowledge spillovers.

To foster these interactions, a knowledge campus should blur office boundaries, mixing talent regardless of company affiliations. It is an ecosystem where people can choose their ideal work environment, either inside or outside the office. Of course, even Tokyo CBDs are not quite there yet. But we have observed meaningful efforts by major developers to expand public spaces within the CBD and broaden the variety of activities available to employees beyond their office walls.

CBDs in other cities are also making strides in this area: La Défense and Canary Wharf recently announced transformation programs aimed at substantially increasing the share of residential properties. Similarly, Lower Manhattan has experienced at least a doubling of its CBD residential population.

Transformation programs

also aim to enhance public spaces by creating vibrant areas that encourage interactions and serve as the backbone of the knowledge campus. For example, the Canary Wharf master plan incorporates a generous open-space and public-realm strategy as a central element.

What CEOs Can Do Today

With the tectonic shift in how we work, selecting an office location has become more strategic than ever. The right choice can attract and help retain top talent while enhancing productivity. But a poor location may lead to the loss of valuable employees, reduced performance among those who stay owing to dissatisfaction and lower motivation, missed opportunities for greater productivity, and ineffective use of space.

In fact, we are already seeing warning signs from employees returning to the office, indicating that spaces and processes have remained unchanged—workers still are not experiencing increased interaction, collaboration, or mentoring. CEOs should act now to avoid blowback.

Select or codesign the right CBD. Start by identifying the CBDs that align with the knowledge campus concept and contribute to higher productivity and engagement by enhancing accessibility, promoting knowledge spillovers, and fostering industry collaboration. Choose the one that best fits your sector both globally and locally.

CEOs’ influence in shaping the ecosystem is growing. The next step may involve partnering with developers, tenant associations, and district governments to integrate elements of the knowledge campus model—mixed-use spaces, pedestrian-friendly environments, and improved transportation access—into broader strategic initiatives.

Align your company with the new CBD ecosystem. This can include several policies and areas of focus:

- Enhance flexible work arrangements. Explore a variety of flexible work models that balance remote work with in-person collaboration. Define office-based tasks that maximize face-to-face value rather than simply focusing on time spent onsite. According to a 2023 BCG survey on hybrid work strategies , employees clearly distinguish between tasks that are more efficiently executed from home and those that yield higher productivity in the office. But many companies’ policies have yet to reflect this nuanced understanding.

- Expand work location options. Reevaluate workspace opportunities taking into account modern practices, such as working from a coffee shop. As previous research from Bond University and the University of Münster suggests, some alternative workspaces can contribute to higher productivity. Separately, the “coffee shop effect”—supported by numerous surveys—demonstrates that ambient background noise in public spaces can enhance productivity and spark creativity.

- Foster stronger professional communities. Encourage employees to connect and partner with peers in their industry, reinforcing the principle that collaboration drives productivity. Companies can support this by providing learning and development stipends, organizing networking events, promoting cross-company projects, and investing in coworking memberships.

- Ensure that workplace policies align with business district realities. Health, insurance, privacy, and reimbursement policies should reflect the new ways employees work—whether in the office, shared spaces, or remote locations. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all model, companies should create adaptable frameworks that accommodate different workforce needs.

- Sell the value. Clearly communicate how the CBD ecosystem enhances employees’ professional growth, productivity, and work-life balance, rather than simply mandating office attendance. As numerous studies on organizational vision and employee engagement have shown, companies that effectively define and share the strategic role of their office environment with their staff tend to foster higher voluntary attendance and employee buy-in.

The most forward-thinking companies will not just adapt to shifting work patterns but actively shape the cities where they operate. Business districts are evolving, and the organizations that engage in their transformation will secure long-term advantages, both for their workforce and their bottom line. The office is no longer just a place—it’s a strategy.