In a world of rapidly changing competition within the green economy, the UK can continue to attract businesses by implementing pro-innovation regulation. Here’s how.

The global economic landscape is shifting rapidly, particularly when it comes to the green economy and clean technology. In recent months, significant moves have been made in the pursuit of a new industrial policy that’s suitable for the massive energy transition needed for a net zero world. With the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Green Industrial Deal proposal coming on top of China’s long-running activist industrial policy, the world’s largest economic blocs are positioning themselves for a very different type of economic competition.

The reasons for this are obvious. There is a significant opportunity in being a leader and winner in the global energy transition, in terms of achieving both net zero and economic growth. It is in this context that the UK needs to consider how it can best achieve its aims and where it can really compete. Not doing so risks missing out on bringing investment, jobs, skills and idea creation into the UK. Furthermore, as massive US, EU and Chinese investment boosts the R&D and productive capacity around green industry and clean technologies, costs will likely reduce quicker than expected and innovation will accelerate − a potential boon for anyone using these technologies or seeking to build a greener economy. Navigating these risks and opportunities will be crucial in determining the future course of the UK economy.

The UK is not alone in facing these issues. From Canada to South Korea, many other countries are grappling with how best to respond. However, for the most part, these countries are already further ahead in their thinking than the UK.

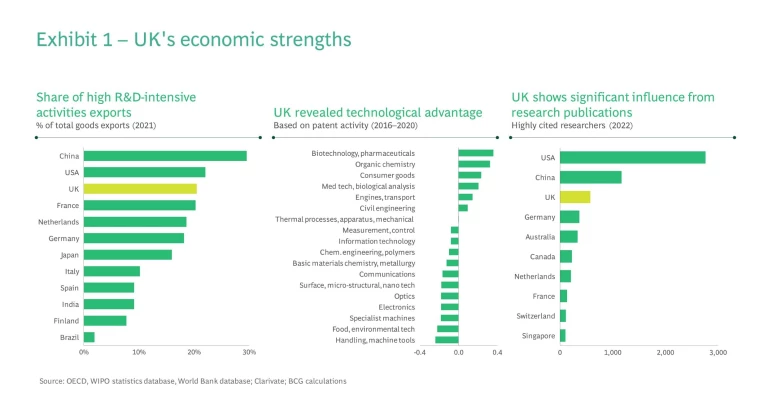

The UK is not going to compete with the US, EU and China on money or scale. So to ensure that it remains an attractive place to invest and do business, it needs to think more creatively and carefully about the tools it has at its disposal. The UK’s advantages lie in services, R&D, innovation, a skilled workforce, world-class universities and research institutes, and manufacturing exports that have high R&D inputs (Exhibit 1). By considering these advantages we can begin to form a picture of where the UK should position itself – specifically targeting upstream and early-stage investment in emerging technologies and industries and their development.

Subscribe to our Climate Change and Sustainability E-Alert.

Direct financial incentives are an obvious mechanism that can be used to foster innovation. But while these should inevitably be part of an overall plan, other tools are also available to the UK. Creating the right regulatory frameworks is likely to be just as important in encouraging early-stage investment, and therefore ensuring that the UK remains economically competitive and capable of achieving its strategic aims for the energy transition and net zero. The EU has already recognised this with simplified regulation a key pillar of its Green Industrial Deal. And while the UK government’s Skidmore and Vallance reviews have started off this process with a particular focus on pro-innovation regulatory frameworks, there is still a lot more that can be done. Similarly, the opposition Labour Party’s proposal for a Green Prosperity Plan demonstrates a clear understanding of the issues but focuses heavily on funding incentives.

The UK is not going to compete with the US, EU and China on money or scale. So to ensure that it remains an attractive place to invest and do business, it needs to think more creatively and carefully about the tools it has at its disposal.

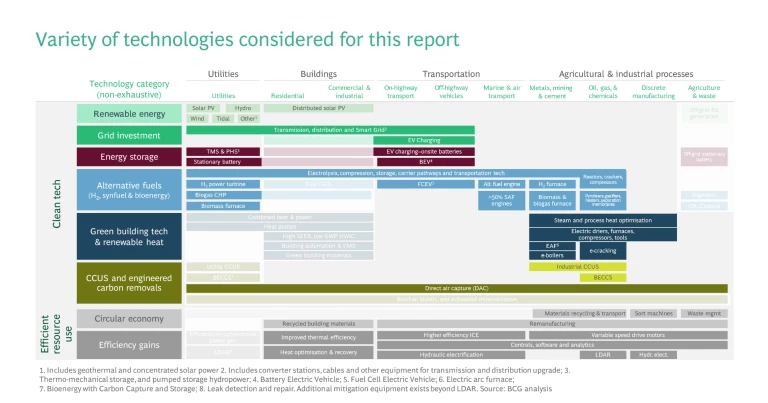

Following a series of consultations with industry and public sector leaders, we believe there are three priority action areas for regulatory frameworks and non-financial incentives. Targeting these areas will be crucial for creating a basis on which the UK can compete in green industries and clean technologies. While not an exhaustive list, our suggested actions can help form part of the non-financial approach that the UK can take in this space:

1. Provide clarity on priorities, plans and expected support

2. Put innovation at the centre of regulators’ operations

3. Facilitate use of trials and testing environments.

Technology and Scope

Provide Clarity on Priorities, Plans and Expected Support

Focus, boldness and long-term commitment are needed to drive innovation. These attributes provide certainty to investors, which in turn would help to attract capital into the UK’s priority areas for innovation and development. To provide additional clarity and encourage greater investment there are four key actions the UK should take:

1. Articulate a clear national strategy which outlines UK focus areas.

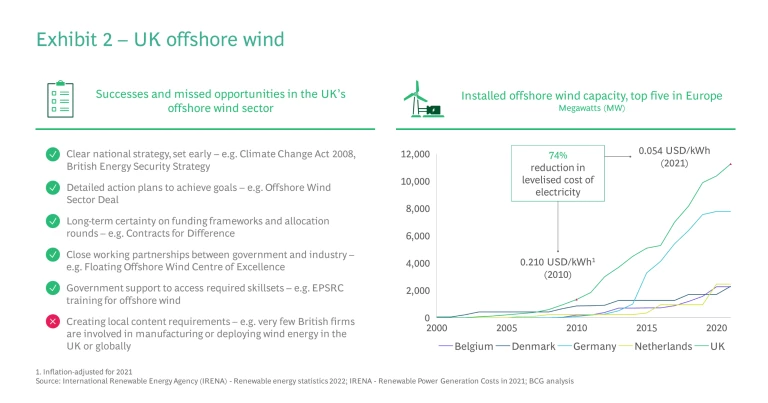

Technologies and sectors where the UK has or can have a competitive advantage need be prioritised. This should be an enduring strategy, ideally securing cross-party support to allow for a seven to 10 year time horizon (as is the case for offshore wind). This would give investors clarity and certainty about government investments. It could also help to de-risk investments across the value chain for these priority areas. The creation of specific institutions and/or programmes which set plans beyond the electoral cycle would be a clear way to demonstrate the certainty and clarity required here.

2. Provide more detailed action plans to deliver on strategic ambitions.

Each national priority should have a detailed action plan. Currently, even where a specific ambition is in place, there is often a lack of clarity when it comes to putting together a detailed roadmap. A few specific examples include:

- 2030 ICE ban − There is insufficient certainty here on the technologies that will be permitted beyond 2030 which is undermining attempts to plan and secure investment. As the ban is not signed into law, there remains uncertainty around the timing.

- UK Hydrogen Strategy – Greater clarity is needed regarding the roadmap for getting from industrial clusters to broader availability, especially in relation to transport and how any hydrogen network across the UK will be structured to reach remote areas which is often where large industrial demand is located. Currently, plans for hydrogen refuelling stations are less clear in the UK compared to the EU, which has outlined its ambition to have a refuelling station every 100km.

- Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) strategy – The Jet Zero strategy identifies a new mandate for at least 10% of jet fuel to be sustainable aviation fuel by 2030, but it is not yet clear how this will be delivered beyond initial funding for a series of SAF plants.

3. Offer long-term certainty on funding frameworks, allocation rounds and business models.

Taking the

energy sector

as an example, there is demand for a more transparent and regular schedule of allocation rounds as certainty of future phases would facilitate investment in the current phase. In the US, outcomes are published at the end of every auction round with clear signalling from regulators throughout the process. It is also crucial not to shift the timings of funding rounds once they have been announced as investors use these to plan their capital investments over time.

4. Set regulations early to encourage changes and innovation within industry.

The UK already has success stories of leveraging regulation to drive innovation (albeit more on supply side than demand side), e.g. offshore wind with renewable energy targets and ‘Contracts for Difference’. It now needs to build on this success to use early regulation to accelerate more nascent technologies and development of emerging industries. In the

manufacturing industry,

for example, there are multiple opportunities to set standards across the product lifecycle that will incentivise industry to innovate: in packaging and material content, in product use and maintenance (a guaranteed lifecycle), or in disposal/recycling. The recent Vallance review, for example, recommended calling for an appropriate regulatory framework for EV battery recycling to support innovation in this area. Given there are potential market failures or negative environmental externalities, government will need to set and drive the agenda in some of these cases if there is truly a desire to see a more circular economy. Leading in innovation in these areas can then deliver benefits as they grow globally.

Currently, the lack of clarity on target areas, funding and action plans means investors and research departments are hesitant to choose the UK as the place to do business. While the steps above may seem small in isolation, they are an important part of the overall positioning of the UK when it comes to attracting investment in green industries and clean tech. Several of them were key to the successful development of the offshore wind sector in the UK (see Exhibit 2).

Put Innovation at the Centre of Regulators’ Operations

The global energy transition requires the development and deployment of new technologies across the economy at unprecedented pace in parallel with continued digitisation. Regulators must give the facilitation of innovation at pace and scale the same importance as their mandates for safety, competition and fairness − requiring them to fundamentally change their approach by putting innovation at the core of their remit and finding a new way of working. Regulators and policymakers must take a proactive role in driving innovation, hand in hand with industry and ensure that risk vs. benefit assessments include the wider benefits of innovation.

There are two key aspects involved here:

1. Regulators must set a framework which helps to facilitate and drive innovation: “regulation for innovation”.

2. Regulators must ensure that regulation is sufficiently capable of adapting and evolving over time: “innovative regulation”.

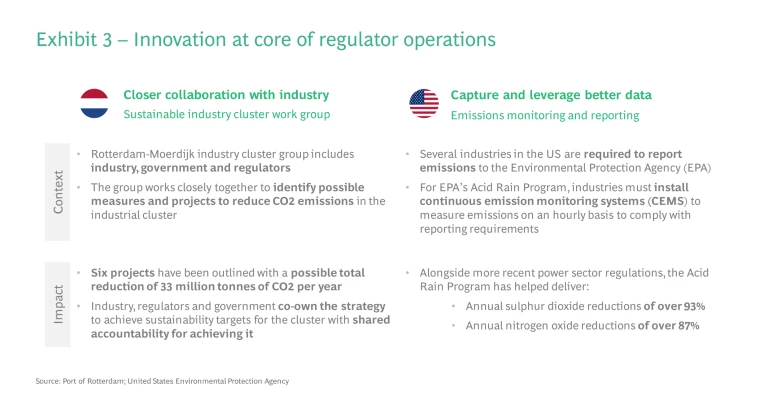

We see four specific actions which can help regulators to fully adopt and deliver on this ambition. Exhibit 3 highlights related examples of best practice.

Regulators should:

1. Find more collaborative mission-focused ways of working together with industry to ensure innovation can scale.

For example, establishing joint taskforces with clear time-bound tech-specific goals in which regulators share the objective of development and deployment with industry. Taskforces would allow greater transparency and faster decision-making. The rapid development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines is a good example of early and continuous dialogue between industry and regulators which resulted in timelines to regulatory approval being significantly shortened. One key aspect involved approvals being granted via a rolling review, which could be an important tool for dedicated taskforces within green technology to encourage rapid deployment from early innovation to scaled technologies.

2. Capture and leverage data to better monitor innovation in real time.

This will support the regulatory risk appetite to adequately reflect the real risk associated with technologies. The London Air Quality Network monitors pollution (e.g. CO2 emissions) in real time from a range of sources including road transport, aviation and industrial processes. The data is used as an evidence base for air quality policy and regulation, including driving the recent expansions of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), an area in London in which drivers of the most polluting vehicles are charged a fee. Key enablers for greater use of real time data will include data sharing platforms between regulators and industries, and supporting legal frameworks.

3. Deepen their technological − particularly digital − expertise and skillset.

It will be key for regulators and policymakers to develop a stronger data and analytics skillset so they can effectively translate data into concrete insights and regulatory actions. With a better understanding of the needs and choices involved in innovation regulators will be able to adopt a forward-looking approach and a greater risk appetite. For example, secondments for regulators in industry, or vice versa, could help to foster this mindset. Technological upskilling could be achieved by recruiting more engineering talent, internal training and broader knowledge exchange with industry.

4. Ensure regulation is adaptive across the technology life cycle.

As many technologies are still relatively new in the clean tech space, regulation tends to focus on the initial build and set up. However as these technologies mature it is important to have regulation in place for their renewal or disposal. An example is repowering mature wind farms at the end of their lifetimes. After the 20-25 year initial planning permission granted for turbine sites, there are three options: to decommission, extend the life, or repower. Current regulation has caused significant uncertainty regarding repowering as it treats these projects as if they are starting from scratch. This has led to missed opportunities for repurposing existing permits and land usage. A specific regulatory framework for this stage of the asset lifecycle would be beneficial.

Taking these steps now would allow regulators to become more responsive to the emerging clean technologies and green industries. If implemented, the UK would become a more attractive place to test and develop these new technologies − boosting investment into the UK, providing downstream benefits for employment opportunities and stimulating the development and export of intellectual property and skills.

Facilitate Use of Trials and Testing Environments

The environment for trials and testing needs to be improved to better facilitate the development of emerging technologies and business models. This is the case for the entire maturity curve, from permits for small-scale testing through to commercial testing and broader scale-up. The following components are crucial for an effective trials and testing regime:

1. Design requirements for funding frameworks to be proportionate to the scale of funds.

For example, a de minimis threshold should facilitate small-scale testing by stripping back administrative requirements for smaller pots of funding. Current funding requirements ultimately deter industry from carrying out trials and small-scale testing. Given their limited in-house resources, SMEs in the UK currently struggle to fulfil the work needed such as auditing to access small sums of funding (£5-£10k/month) from the Innovate UK fund for example.

2. Streamline permit processes for testing and post-testing approval.

In the transport sector some heavy goods vehicles (e.g. longer semi-trailer) have been in testing for more than 10 years. To overcome issues like this, permit and planning processes need to be streamlined in the context of deploying the infrastructure required for testing (e.g. large supply of pipes tanks, and electrolysers for hydrogen testing), as well as allowing manufacturers to test different end use sources for the production process. Where technologies are being tested at a small and/or local level, permits and approvals should be provided through a further streamlined process.

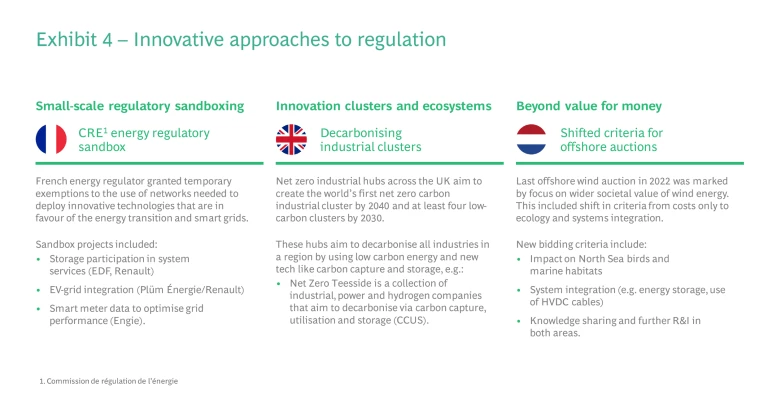

3. Increase use of localised innovation clusters to offer a test environment for early-stage innovative technologies and new business models.

A successful example of this is the hydrogen cluster approach which has established localised supply chains of hydrogen producers, users and distributors. A cluster can facilitate the cooperation of all actors involved to ensure innovative progress across the value chain. The role of regulators is pivotal in providing the right infrastructure and environment to facilitate testing.

4. Increase use of regulatory sandboxing to expedite early-stage testing.

The Civil Aviation Authority has set up the CAA Regulatory Sandbox which allows participants of the

Future Flight Challenge

to demonstrate their products and services in live environments, even where there are gaps in current regulation. This approach identifies the unknowns and risks of new innovations upfront and helps to design relevant mitigations that are explored in a cycle of testing and learning. Schemes like this help to maximise safety and regulatory readiness without delaying the innovation being developed.

Two additional thoughts are important here: the results of sandboxing should be shared back to revise real regulation; and a transition should be facilitated where testing can be taken from small-scale sandboxes to testing in real-word commercial environments. In response to the Vallance review, the government reported that it would explore whether regulatory sandboxes (e.g. for innovative use of waste products) could be aligned with the Investment Zones programme. Given that the Investment Zones programme has clearly been designed solely with levelling up in mind rather than innovation, our view is that this could result in the direction of investment and trials being constrained. Sandboxes should be linked to the areas (geographic, sector, etc.) that will have the most beneficial impact on innovation.

Improving the environment for trials and testing is a vital step in the process of creating the best conditions for innovation. If testing and trials of new technologies become easier to undertake in the UK, it would increase the prospect of investment, research and industry development locating here. Examples of best practice are outlined in Exhibit 4.

Infrastructure Planning Will Be a Key Enabler

Encouraging investment into early-stage green industries and clean technology projects will not be successful without reliable and flexible infrastructure. For example, the electricity grid and hydrogen networks will be vital enablers of innovation given the change in both size and type of energy demand. The challenges with modernising this type of infrastructure to make it fit for the future has been covered extensively recently, such as the

NAO report

on 'Decarbonising the power sector’. There is plenty already happening in this space with initiatives such as the review by Electricity Networks Commissioner Nick Winser, due to be published this summer, on how to cut the development time for transmission network projects in half. A Future System Operator (FSO) will also be launched by 2024, which has the potential to be a game changer in terms of strategic network planning and expert advice. Getting all this right will be crucial to supporting innovation and therefore vitally important when it comes to the UK's ability to compete globally.

Moving Beyond Value-for-Money Decisions

Alongside these four key areas for action there is a related but separate point which the UK must grapple with. When setting ambitions, plans and funding frameworks, it is important to recast and think more broadly about what value for money really means. As well as upfront cost, it must encompass positive long-term economic impact and the adequate capture of domestic benefits. There is an important balance to be struck here. The UK cannot afford to slip into pure protectionism, but also must accept that the old dichotomy of free traders vs. protectionists does not reflect the nuance of the global trading landscape today. The economic context has shifted significantly, with global trade flows being marked by persistent imbalances and interventionist policies designed to maintain those imbalances and distort trade. Of course, where possible the UK should cooperate and seek to avoid these sorts of distortions. But when cooperation and coordination are not a priority for the largest global players in this space, the UK must have an alternative. Where large amounts of taxpayers’ funding are being invested, it makes sense to ensure there is a longer-term return for the domestic economy and/or local area rather than a sole focus on the initial outlay or cost.

For example, the Netherlands recently shifted from an emphasis on cost reductions to demonstration of wider societal value in relation to certain permit auctions and government investments (e.g. level of knowledge sharing, reinvestments, domestic job generation) (see Exhibit 4). Local content requirements (particularly around capex) are increasingly used to encourage local production and employment. This is one of the key tools in the US Inflation Reduction Act, offering tax credits for renewable energy projects that meet certain local content requirements for steel, iron and manufactured products. The UK government has begun a review that explores how best to look at “non-price factors” in awards of ‘Contracts for Difference’ for renewable energy production, but it remains well behind the concrete actions outlined by other countries.

Where large amounts of taxpayers’ funding are being invested, it makes sense to ensure there is some element of longer-term return for the domestic economy and/or local area, rather than just a pure focus on the initial outlay or cost.

The Time Is Now

The UK has a strong recent history when it comes to green industry and innovation – from success in the deployment of offshore wind to the use of industrial clusters for clean hydrogen. Use of non-financial incentives has often been part of this. The economic landscape is changing and the UK must look to its strengths and areas of comparative advantage instead of only replicating what others have done. The recommendations set out above are just one part of what is likely to be needed but we believe it is a crucial part. We must start to make some of these changes now before these large industrial policies begin to dominate global supply chains. There is no time to waste.

About Us

The

The