The creative industries are jewels in the UK’s crown. They make an outsized contribution to economic growth, jobs and Britain’s soft power abroad. But a changing landscape globally means that this significant source of UK competitiveness is increasingly at risk, and a renewed strategic focus is needed. In this paper we propose four practical steps to cement the UK’s leading role in the global creative economy into the future.

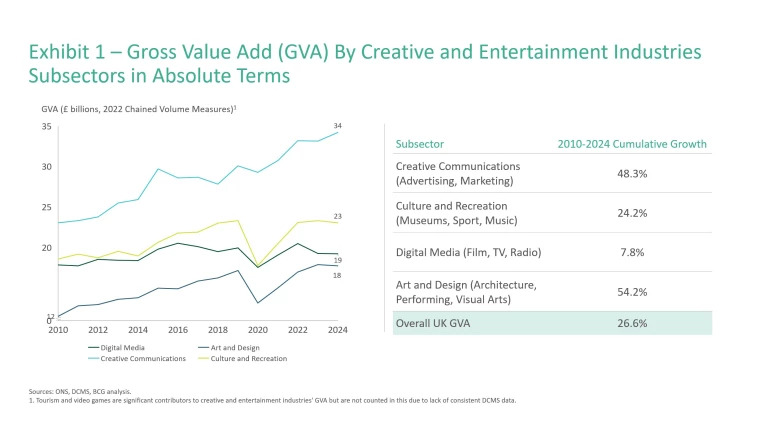

To fully understand the strength of the sector as a whole, we have built a new definition – removing IT and software and including culture and sport – which we term the UK’s creative and entertainment sector. In 2023, this sector had Gross Value Added (GVA) of £94 billion and saw 31% growth vs. 22% growth for the UK as a whole, in real terms, between 2010 and 2022 (Exhibit 1). This means it was the third-fastest growing sector of the UK economy (after admin and support services and professional and technical services) in this period.

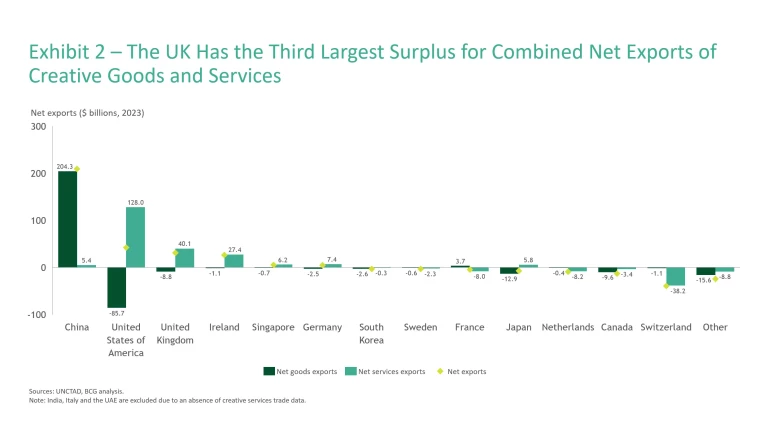

The UK also consistently has the third-largest net trade surplus in creative goods and services globally (Exhibit 2). Thanks to a wide array of cultural assets, the sector brings a wealth of broader social benefits, from improving individual wellbeing to helping make communities an attractive place to live.

It is a fragmented and diverse sector. This supports huge amounts of inventiveness and flexibility, but it can also harm productivity. As digital distribution allows even small firms to reach large audiences, there is a premium on finding the balance between these two effects.

This said, the UK’s leading role is at an inflection point. Supporting this diverse industry in a complex global landscape is more important than ever. We find four megatrends reshaping the sector.

Four Megatrends Reshaping the UK's Creative and Entertainment Sector

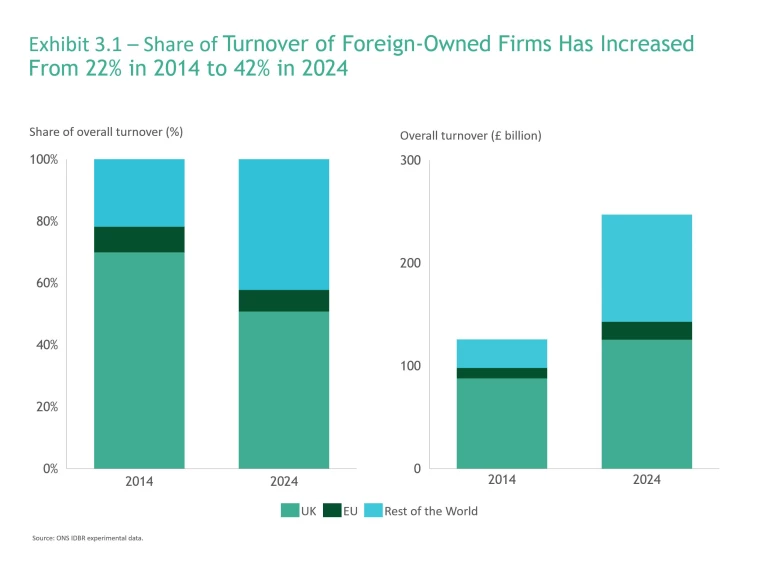

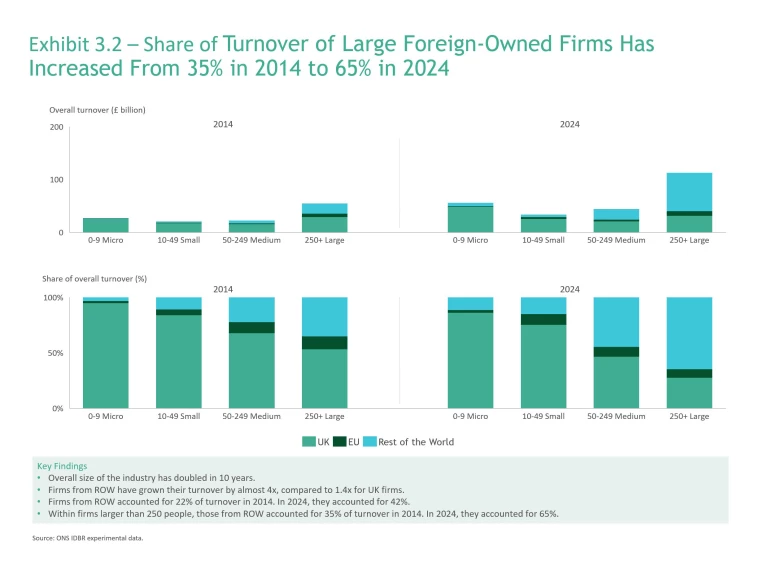

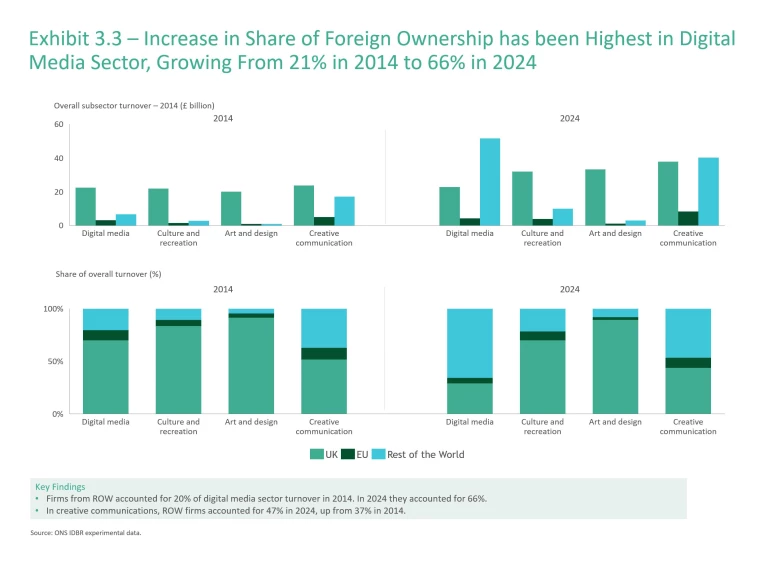

- The changing way people consume content (via streaming services and tech platforms) has resulted in global firms doubling their share of UK turnover. In 2014, foreign-owned firms accounted for 22% of turnover in this sector in the UK. This has now risen to 42%. For large firms, it has increased from 35% to 65%. This has had benefits, for example bringing UK content to new audiences around the world. But it also results in a lower share of UK revenue going to domestic firms, such as the Public Sector Broadcasters (PSBs). In the long run, this could reduce reinvestment into British-made content. For example, although almost all turnover growth in the digital media sector (which includes TV and film) over the past decade came from non-UK firms, in 2021 £5 billion of UK TV production spending still came from domestic firms, compared to £1.8 billion from international firms.

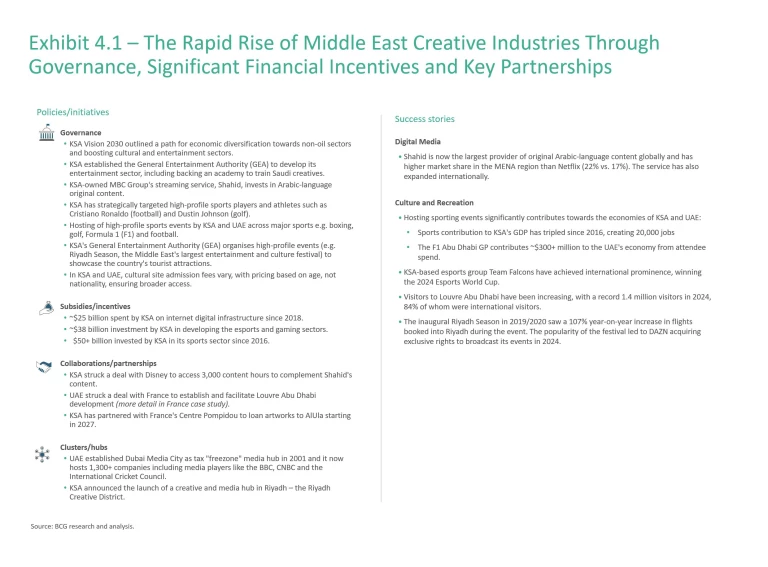

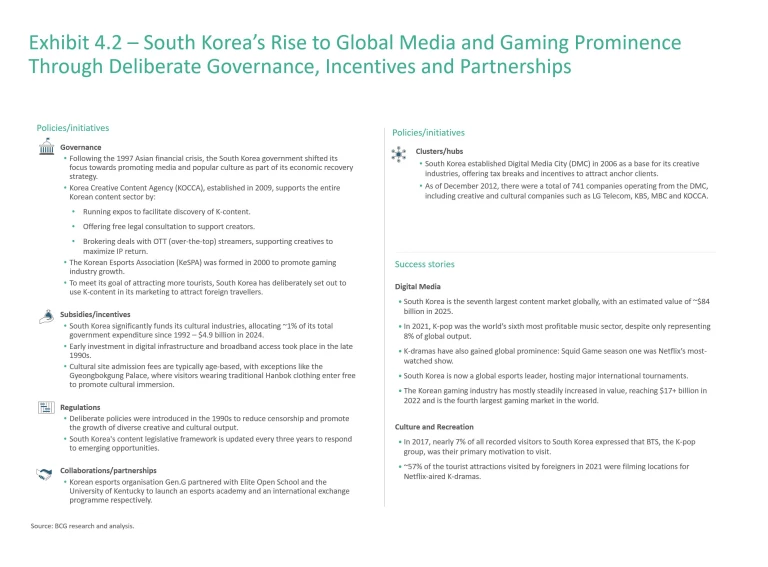

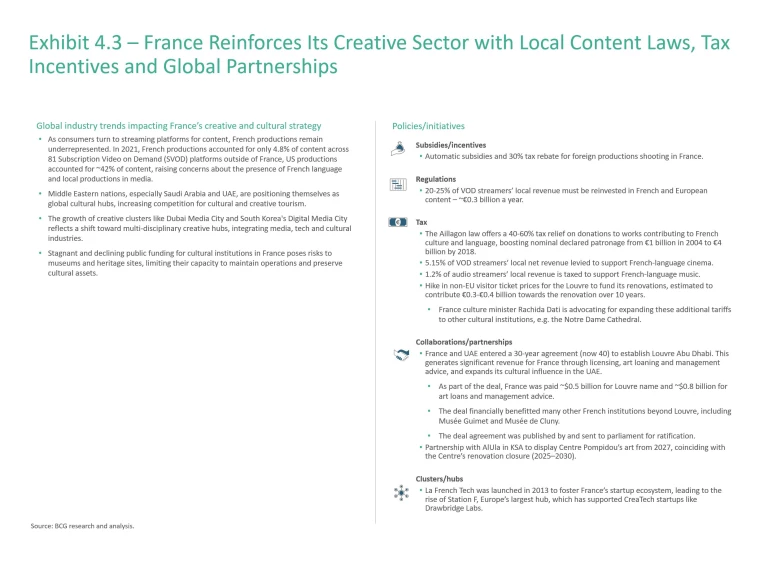

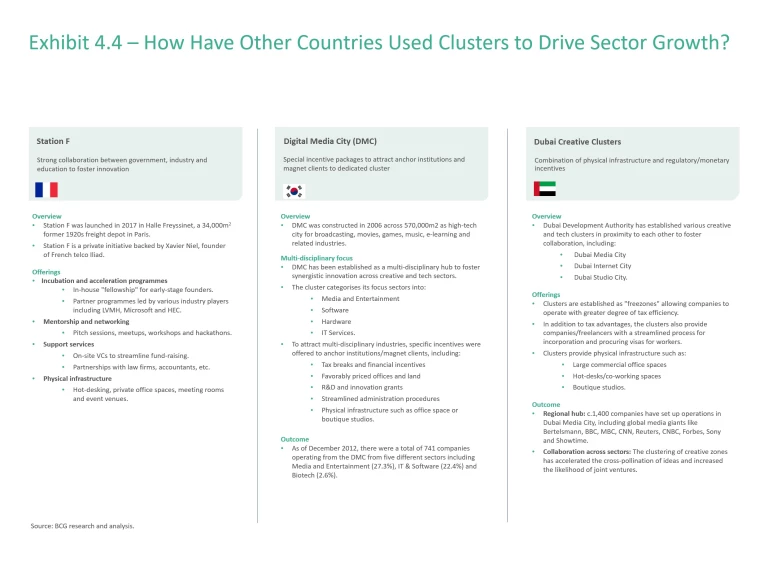

- Countries are making significant policy interventions to build their creative and entertainment sectors. Two common elements seen here are the creation of multi-disciplinary clusters to drive growth, and the leveraging of international partnerships to exchange expertise and open up new audiences (particularly for cultural institutions). Beyond this, policies vary. Countries in the Middle East are putting significant amounts of funding into their sector (for example investing over $38 billion in recent years to develop its gaming and esports industry), while South Korea has adopted an end-to-end strategy from training to supporting content owners in striking the best deals for their IP. Meanwhile, France continues to apply levies (e.g. on streamers and platforms) to drive investment into its domestic industry. This is creating a more complex and uneven landscape globally. The UK has not updated its own policy approach for some time.

- Artificial intelligence (AI) is disrupting content creation. This brings opportunities but also raises questions about employment and returns in the sector. AI makes content generation more accessible and significantly reduces the marginal cost of artistic output. For example, Oscar winning Everything Everywhere All at Once used AI to reduce the number of visual effects artists needed from a typical 160 to just nine. There are also significant concerns that AI models are being trained on copyrighted material without fair compensation for the creator/owner. Together, these factors could reduce reinvestment into content creation and affect the viability of some businesses and institutions in the sector.

- A shortage of certain skills in the sector, exacerbated by technological disruption, poses a risk to future growth. Despite the UK’s world-leading arts universities, skills gaps are challenging the creative sector and risk becoming more acute as AI reshapes the roles required. The graduate-heavy workforce (68% of creative sector employees are degree holders vs. 22% economy-wide) is increasingly poorly prepared due to limited industry join-up with academic and training institutions, with a lack of digital skills most pressing. There have also been rapid declines in those studying arts in primary and secondary education.

Any forthcoming strategy must ensure that the key inputs for this sector – skills, capital, infrastructure, technology and regulation – continue to be robust in the face of these trends. Otherwise, they risk quickly being outpaced. This means moving away from short-term tactical conversations, too often narrowly focused on government funding, and towards a more active and strategic policy approach. We see four practical steps which can help.

Four Practical Steps Which Can Help

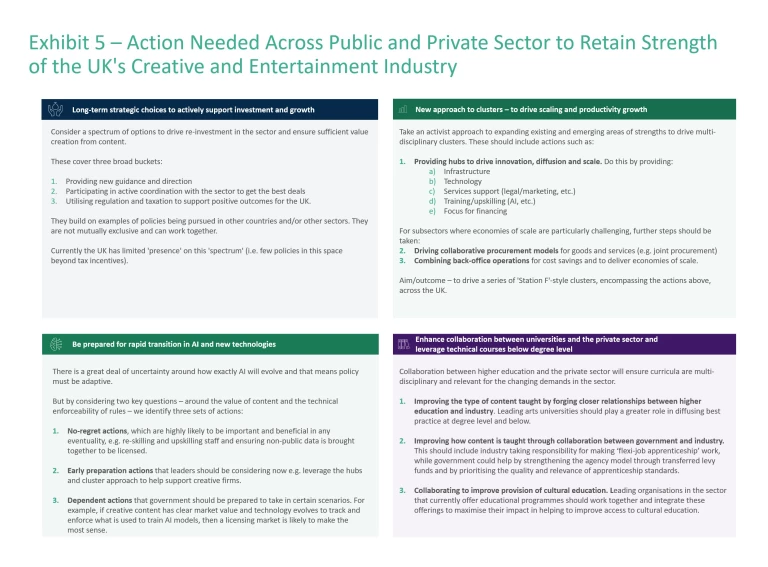

Make long-term strategic choices to actively support investment and growth. Options range from less to more activist, including:

a. Providing new guidance and direction. For example, this could involve setting non-binding targets for global firms to invest a share of their UK revenues into UK produced content (potentially as a precursor to more binding requirements).

b. Participating in active coordination with the sector to get the best deals. This could include a new agency helping firms to strike licensing or content deals with streamers, AI firms or international partners. Support for the commercialisation of content could also be offered, where appropriate, such as bringing together public assets in the National Data Library, as well as creating a clearer rights framework to allow maximum returns on licensed content.

c. Using regulation and taxation to support positive outcomes for the UK. The key step here is ensuring UK tax incentives are competitive and regulation is fair. Other countries have also taken further steps, though these have greater trade-offs. These include strengthening local content requirements within existing tax incentives, cultural institutions charging foreign visitors, allowing cities/regions to levy tourist taxes with revenues directed into the creative and cultural sector and, at the most extreme end, direct levies on parts of the sector to support reinvestment. The UK should study the effectiveness of these to judge whether any are worth pursuing.

Adopt a new approach to clusters to drive scaling and growth. This would support the UK’s diverse sector to fully take advantage of the opportunities afforded by the changing landscape. There are two key elements to these clusters – they should be multi-disciplinary and innovation hubs must be central to them.

a. Developing innovation hubs to support the competitiveness of UK firms. Create innovation hubs which provide infrastructure (e.g. office space), technology (e.g. cutting-edge studios), wrap around support services (e.g. marketing, legal and business support), training (e.g. developing AI use cases) and opportunities for investment (e.g. by providing a single place to showcase investment opportunities).

For the not-for-profit part of the sector, where achieving economies of scale can be more challenging, other steps should be taken, including:

b. Driving collaborative procurement for goods and services. Businesses and public institutions should look to jointly procure goods (e.g. sets, costumes) or services (e.g. security, cleaning, catering) to boost scale and reduce cost.

c. Combining back-office operations. Taking the above a step further includes merging services like admin, office or IT support, which in turn can help to provide pay and role progression.

Be prepared for the rapid AI transformation. It is impossible to know exactly how AI will evolve and that means policy must be adaptive. But by considering two key questions – around value of content and technical enforceability of rules – we identify three sets of actions:

a. ‘No-regret’ actions which are highly likely to be important and beneficial in any eventuality. Reskilling and upskilling staff and ensuring the non-public data that the UK public institutions hold is brought together so it can be licensed most effectively.

b. ‘Early preparation’ actions that leaders should be considering now. Leveraging the hubs and clusters approach will help creative firms access AI infrastructure, technology and training to help spread best practice.

c. ‘Dependent’ actions government should be prepared to take in certain scenarios. If creative content has clear market value and technology evolves to track and enforce what is used to train AI models, then a licensing market that follows a more traditional copyright and IP protection approach is likely to make the most sense, providing it is sufficiently light touch for both parties. If content doesn’t have sufficient value and/or it is not possible to legally or technically enforce content protection, the focus should turn to looking at other active policy instruments to drive reinvestment into the sector and to support content creation in the UK.

Enhance collaboration between universities and the private sector. Leverage technical courses below degree level to ensure curricula are multi-disciplinary and relevant for the changing demands in the sector.

a. Improving what content is taught by forging closer relationships between higher education and industry. Leading arts universities should play a greater role in diffusing best practice. This should take place at degree level and below, to strengthen the provision of higher technical courses (i.e. those below degree level) as entry points into the sector. New collaborations between arts universities and business/tech schools could also help to embed multi-disciplinary training into traditional creative arts degrees.

b. Improving how content is taught by embracing and strengthening technical routes. Collaboration and flexibility between government and industry is needed to improve the apprenticeship system. This should include industry taking responsibility for making ‘flexi-job apprenticeship’ work, while government could help by strengthening the agency model through transferred levy funds and ensuring the quality and relevance of apprenticeship standards is a priority.

c. Sector leaders collaborating to improve provision of cultural education. Given the large reduction in access to cultural education at primary and secondary school level, leading organisations in the sector that currently offer educational programmes should work together and integrate these offerings to maximise their impact in helping to improve access to cultural education.

The next few years are going to be crucial in determining the long-term future of the UK’s creative and entertainment industries. The UK’s historic success and strong platform to build on are evident. But this alone cannot be relied on. A coherent strategy that addresses the megatrends reshaping this industry is urgently needed. Thankfully, this does not require huge amounts of new funding. There are some targeted policy actions which, when combined, can help this sector to continue to deliver the economic and societal benefits that it has historically provided – even in the face of a rapidly shifting global landscape.

Subscribe to receive the latest insights on Technology, Media, and Telecommunications.

About Us

BCG's Centre for Growth brings together ideas, people and action to drive the UK forward. We work with our global expert network to identify transformational opportunities, connect key decision-makers and build coalitions for change. We offer long-term strategic insight, extensive cross-sector expertise, platforms for dialogue and bias to action.