The energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy is one of the most pressing issues facing the UK and the world. We face unprecedented challenges, including economic uncertainty, global instability and the cost-of-living crisis. We must adopt a broad energy mix, incorporating a variety of low-carbon fuels and renewable power sources – including clean hydrogen – to achieve net zero.

Developing and implementing a strong clean hydrogen strategy could deliver significant economic and industrial benefits, establishing the UK at the forefront of a growing global industry. It could also contribute to economic prosperity and support the UK Government’s levelling up strategy. Investment in innovation today could deliver significant long-term benefits for the UK economy and its population.

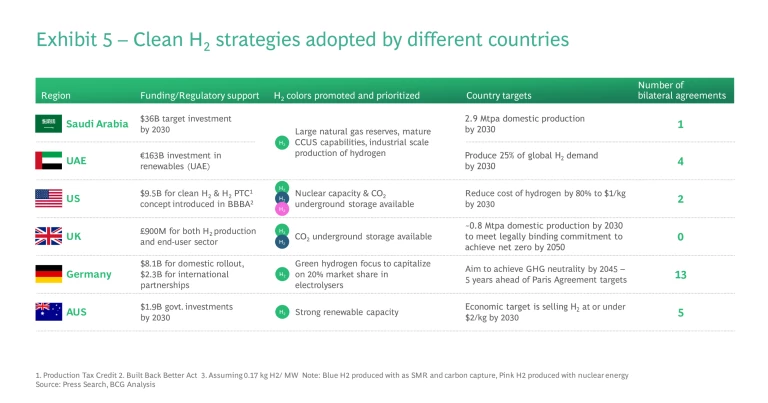

The challenge for the UK is establishing itself as a leader in an emerging market sector where global competition is high. The UK isn’t alone in identifying and having access to this opportunity. Many other economies, in most cases larger than the UK, are attempting to establish their position at the forefront of hydrogen technology. To compete, the UK must move quickly, leveraging its strengths. Failing to do so could cause the country to fall behind competitors.

We have identified three critical recommendations for the UK:

- Double down on and move more quickly to build industrial clusters to provide greater clarity for both supply- and demand-side investments.

- Develop and implement local content requirements and provide specific research & development (R&D) support for the hydrogen sector to develop intellectual property. This will ensure economic benefits are fully realised in the UK, avoiding the mistakes made with offshore wind.

- Establish international partnerships to fill local capability gaps and maximise the export potential of the hydrogen sector.

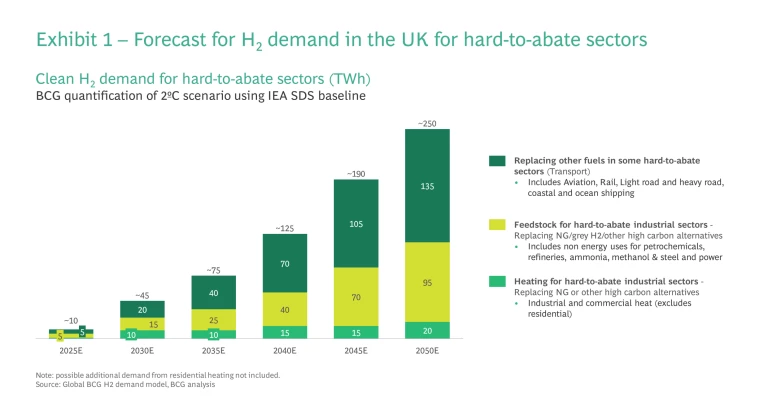

Global Hydrogen Demand Is Rising

Domestic and global demand for hydrogen is forecast to skyrocket in the next decade. Analysis performed by BCG into the future requirements for low-carbon fuels established that we would need approximately 380 million tons of low-carbon hydrogen and its derivatives per year if we are to limit global warming to 2°C. This figure rises to an incredible 565 million tons per year if we want to achieve the Paris Agreement goal of limiting climate rise to 1.5°C. Exhibit 1 illustrates the rapidly growing domestic demand for hydrogen in the UK.

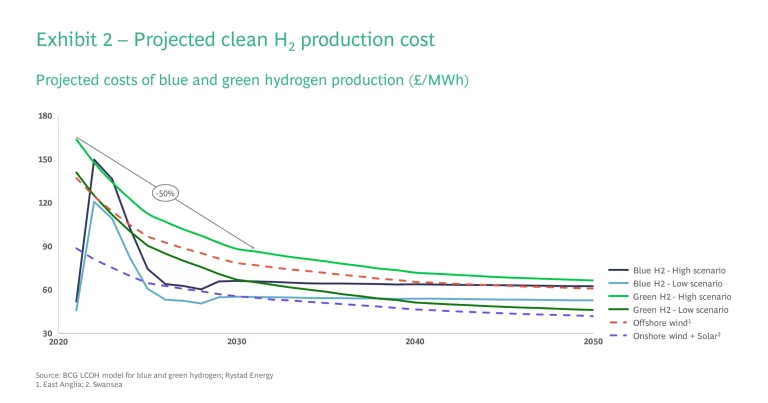

These predictions are based on the cost of hydrogen falling to competitive levels – something we forecast will happen sooner than many expect. History has demonstrated that new energy technologies can quickly become competitive – for example, we have seen both offshore wind and solar rapidly achieve cost parity with some fossil fuels. If hydrogen follows similar trajectory and technology curves as other renewable energy technologies (wind, solar, battery), we could see production costs fall by up to 50% by the end of the decade. This is an optimistic target, but we believe it is within reach with the right investment, approach and strategy. For instance, the recent US Inflation Reduction Act provides a welcome boost for hydrogen and has the potential to dramatically reduce the costs of production worldwide. Moreover, it demonstrates the potential for the technology and the investment being made to deliver it.

The Benefits of Clean Hydrogen for the UK

The role of clean hydrogen in achieving net zero is already well known. It will play a crucial role in decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors such as shipping, aviation, and cement and steel production. Moreover, hydrogen can play an essential role in plugging the energy gap when the availability of already established renewables such as wind and solar fluctuates, partly by providing long-term storage when there is an excess of renewable energy. The result of this is a more flexible, diversified and robust energy supply that is less vulnerable to disruptive shocks.

There are several other benefits which could emerge if the UK becomes an early investor and global leader in clean hydrogen:

Growth: According to an economic impact assessment published by the Hydrogen Taskforce in 2020, clean hydrogen is expected to add £18 billion in gross value added and 75,000 jobs in the UK by 2035. This is much higher than advancing offshore wind, which is expected to add 60,000 jobs. Furthermore, clean hydrogen is a high-tech, high-productivity industry. Traditionally the UK has performed strongly in such industries thanks to its skilled workforce and culture of innovation.

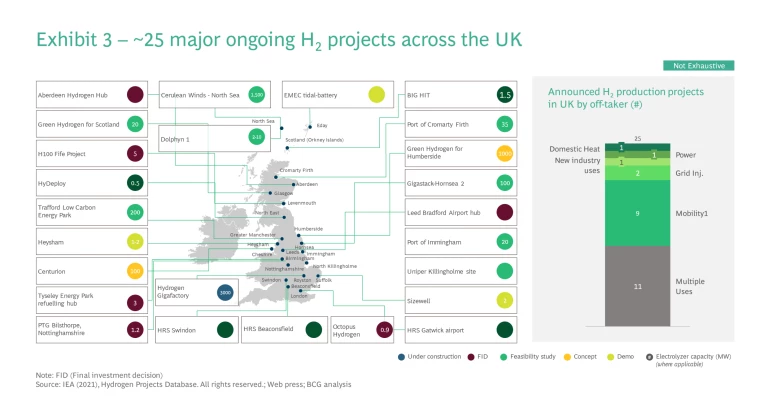

Levelling up: North-east and north-west regions are in a strong position to lead and benefit from the hydrogen transition. These post-industrial areas are a focal point for ‘levelling up’, the UK Government’s strategy for stimulating growth in areas which have fallen behind. Much of the investment in the production and distribution of clean hydrogen typically occurs near industrial clusters located across the UK. Growth and jobs stemming from this industry will be spread across the UK, as the map of existing hydrogen investment shows below.

Energy security: The UK is ranked fourth globally in the World Energy Council’s 2021 Energy Trilemma Index – energy security, energy equity and environmental sustainability. Of these critical areas, by far the weakest here is energy security, where the UK ranks 19th globally. The UK’s energy security vulnerabilities were exposed this year when consumers and businesses saw significant rises in energy bills due to the rising wholesale gas and commodity prices. Having reliable domestic clean hydrogen capacity can help improve energy security in two ways. First, it can improve resilience, helping to support domestic energy supply when needed. Secondly, it can also reduce the UK’s reliance on overseas energy, which is at risk from external shocks, such as geopolitical instability or restrictions on certain rare critical minerals that are required for other technologies (e.g., lithium-ion batteries).

Exports: By investing early and building the right ecosystem and expertise, the UK could become a crucial source of clean hydrogen and hydrogen expertise. We see three key export opportunities for clean hydrogen:

- Energy exports: directly export hydrogen or related forms of energy. This itself comes in three forms – hydrogen, ammonia (and other materials used to transport hydrogen) and embedded in other exports (e.g., where they are used in manufacturing processes).

- Manufacturing exports: export components or technology involved in hydrogen production/supply chains.

- Services exports: export expertise in hydrogen production, storage and/or transportation, including intellectual property. There are significant advantages to being the first (or amongst the first) to market.

There are few, if any, other technologies in the energy space that tick so many boxes for the UK.

The UK Has Several Competitive Advantages

The UK has several strengths it can build on in the hydrogen space. These, combined with the benefits mentioned above, highlight why the sector should become a focus area for the UK’s net zero and wider economic growth strategy.

Defining the Problem

Currently, the hydrogen sector in the UK faces three key challenges:

- Solving the ‘chicken and egg’ problem – Producers need sufficient guaranteed demand to give them the confidence to build large-scale production facilities, which are critical to reducing production costs. Similarly, end users need a reliable supply of hydrogen at an acceptable cost to consider making the upfront investments required to convert their equipment/processes to hydrogen. Presently, both sides are waiting for the other to move.

- Ensuring broad economic benefits accrue in the UK – The UK has not always succeeded in maximising the benefits of new energy technologies. Achieving this is crucial if hydrogen is to drive economic growth and play a role in the energy transition.

- Remaining internationally competitive – The opportunity in this space is not going unnoticed. Several countries are already positioning themselves as leaders in clean hydrogen by earmarking significant funding levels for research and deployment and entering bilateral agreements to fill capability gaps.

What the UK Needs to Do to Become a World Leader in Clean Hydrogen

To be successful in this space, the UK needs to tackle these issues head on.

1. Double down and move faster to develop industrial clusters

To solve the ‘chicken and egg’ supply/demand conundrum, the UK must accelerate the development of hydrogen projects, getting them up and running as soon as possible. It must focus investment on developing regional industrial clusters. These clusters can capture multiple users across the hydrogen ecosystem within a geographical area – providing crucial economies of scale. Localisation will enable the UK to create sufficient scale with less orchestration required from national-level plans. Clusters can help provide a variety of local options for offtake, which in turn reduces the risk for demand and supply investments.

This approach will require a clear step-change from the way things operate now. Today, there are a host of technical pilots scattered around the country, with each player making point-to-point decisions, creating silos across the system. A few clusters have begun to emerge, such as HyNet or East Coast, which have produced strong partnerships between producers, offtakers and transport and storage providers. This provides an opportunity to start with ‘minimal viable clusters’ (around ~100-200MW) and scale up when ready.

To solve the ‘chicken and egg’ supply/demand conundrum, the UK must accelerate the development of hydrogen projects, getting them up and running as soon as possible.

To enable the development of clusters, we recommend:

- Developing a plan for how to update the existing gas network, including how much should be dedicated to hydrogen, where new pipelines will be needed, and the level of demand for blending hydrogen into the current gas supply once the technology is fully proven. This could be done at a regional level in sync with industrial clusters. For example, hydrogen for residential heating is unlikely to be a major use case in the short-term, but it can provide useful source of reserve offtake for industrial clusters, helping to de-risk investments in production.

- R&D tax credits for any spending relating to hydrogen, for example, allowing up to 25% of hydrogen related R&D spend to be recouped.

- Long-term super deduction of 130% for any capital spending relating to hydrogen spending (from either a supply or demand perspective) to encourage investment in the UK.

- Creating a new centralised portal to connect different players within the ecosystem and encourage clusters. The US has already created something similar in the form of its H2 Matchmaker, which seeks to connect hydrogen suppliers and users with collaborators and opportunities to expand development toward realising regional hydrogen hubs.

There are also broader measures which would help to solve the ‘chicken and egg’ problem and boost industrial clusters – these need to be considered in the wider net zero context beyond just hydrogen.

- Implementing a carbon border tax. Several countries are considering a form of a carbon border tax. There are many considerations behind adopting one. From a hydrogen perspective, if one were adopted in the UK, it would make a significant difference for the adoption of industrial users where the carbon content of their products and/or competitors is taxed. As a result, utilising hydrogen within the production process could begin to look far more attractive.

- Developing robust green standards. Regulations and standards which require certain levels of green content or mandated carbon/emissions requirements could make a significant difference to industrial users investing upfront in converting to hydrogen (or to other sources of renewable energy where relevant). For example, requirements around using low-carbon building materials for all new residential buildings.

2. Adopt measures to ensure economic benefits are realised

The UK ranks second globally in terms of installed offshore wind capacity. As a share of its overall energy supply, the UK is the world leader. The deployment of offshore wind is rightly seen as a success story for the UK. And yet, it is also a story of missed opportunity. The UK has successfully introduced renewable energy into the energy mix but failed to turn it into a driver of growth or development.

Despite the UK producing much more wind energy than its peers and more relative to its size than almost any other country, there are very few British firms involved in the manufacturing, development or deployment of wind energy in the UK or globally. The UK Government rightly helped to subsidise wind power development through its contract for difference (CfD) regime, and yet few, if any, firms in the UK could take advantage of it. RenewableUK has estimated that just 29% of capital expenditure on offshore wind projects is from UK content, up from 18% in 2015. This is despite CfDs for the sector being in place since 2013. The UK is now attempting to rectify this through requirements around UK content within supply chains in the new Offshore Wind Sector deal, but it is much harder to do this late in the day.

To avoid repeating the same mistakes, the UK must learn lessons from its experiences with wind energy and from the successes of other countries. Denmark, for example, provides a useful case study of how wind power has been used to drive economic development. Similarly to the UK, Denmark doesn’t have huge market scale like the other key players in the offshore wind market. Yet, Danish firms have managed to secure a significant share of the market and are known globally for their expertise in this sector.

The deployment of offshore wind is rightly seen as a success story for the UK. And yet, it is also a story of missed opportunity.

Specifically, we recommend the UK should:

- Develop early-stage projects. For example, Danish firms sought early on to establish a portfolio of offshore wind projects across Europe (e.g., in Poland, Sweden, Spain and Greece) and had early-stage projects in Denmark and the UK (e.g., Middelgrunden and Race Bank). As a result, they tapped into global demand early, providing them with significant expertise and enabling rapid transformation.

- Make the most of its track record on financing frameworks for renewable projects. The UK is one of the world’s leading financial centres, with a proven track record of combining public and private funding to drive renewable energy projects. There is strong institutional knowledge of how to design the business models necessary to support the hydrogen transition. Often, investors will take on local partners to help navigate investments into certain jurisdictions, but this is rarely necessary in the UK. This puts the UK in a leading position to attract investment into renewable energy solutions, such as clean hydrogen.

- Leverage private sector partnerships to achieve scale. Danish firms partnered with other European companies to collectively achieve scale, including:

- Securing a partnership to source wind turbines from Germany.

- Acquiring installation providers to reduce the risk of bankruptcies across the vertical value chain as they moved from onshore to offshore.

- Adopt local content requirements with an intellectual property focus. An early focus on well-constructed local content requirements can play an important role. Many countries have deployed these recently, particularly in the renewable energy sector. These should be targeted, establishing that a certain percentage of CAPEX or manufacturing supply chain should be from the UK. This should also be supplemented with further supply chain support. For example, a local content requirement for electrolysers wouldn’t make sense without further support to ensure their supply chains can access necessary raw materials, particularly rare earth minerals. Any local content requirements should also be temporary and only apply for an initial wave of CfDs, for example, up to 2030. Finally, as recommended by the Whitmarsh Supply Chain review into offshore wind, the UK should focus on developing intellectual property (IP). This means including requirements for a share of the total capital cost to incorporate IP owned and developed by UK companies.

3. Build international partnerships

The UK has been accelerating its efforts to develop clean hydrogen. The British Energy Security Strategy (published in April 2022) doubled the previous production target to 10GW, with the ambition that at least half of this would be green hydrogen. Many other countries have set similar targets, but the UK lags behind them in one aspect, which could prove crucial in achieving this target. The UK does not currently have any bilateral agreements, while other countries have moved quickly in this space. These agreements broadly fall into three categories:

- Securing trade routes (connecting demand and supply)

In August 2022, Germany signed a green hydrogen import agreement with Canada, using ammonia as a safer and more secure way to transport hydrogen. Canadian companies, which specialise in the development of green hydrogen and ammonia production, storage facilities, and transportation infrastructure, have signed memorandums of understanding with German energy companies that guarantee offtake of a million tons per annum, starting from 2025. - Technology sharing and transfer

In 2021, New Zealand and Singapore established a framework for future cooperation enabling joint research, development and pilots. - Entering joint ventures

A South Korean consortium has signed an agreement with UAE firms to build a $1 billion green hydrogen and ammonia production hub in Abu Dhabi to produce up to 200,000 tonnes of green ammonia each year.

While the UK does have areas of competitive advantage in developing a clean hydrogen economy, it should establish partnerships where there are gaps. At this stage, agreements which focus on sourcing demand or supply should not be the priority. Domestic supply needs to develop in the UK to provide evidence that there is demand, particularly once a CfD is in place.

Therefore, the UK should target the following:

- Bilateral agreements focused on technology transfers and R&D. Share early-stage learnings to bring down cost curves.

- Joint initiatives to share the burden of large investments in early-stage pilots and development projects which in turn will likely help bring down cost over time.

- Partnerships to address supply chain constraints. Finding resources for important parts of the process – such as electrolysers – is particularly challenging. Agreements to secure supply chains with countries that have some of those resources could prove beneficial. The content imported from countries where the UK strikes international agreements could also then count towards the local content requirements set out above, as could UK content exported to them.

Given these aims, the countries which the UK should target for hydrogen partnerships include: the US (from both a technological and investment perspective); Canada (resources and technology); Germany (technology and manufacturing); South Korea (technology and manufacturing); and the Middle East (investment and supply if needed).

Of course, this doesn’t apply solely to the public sector. Private sector leaders should seek international partnerships where relevant to accelerate their developments. They do not need to wait for public sector support or action to begin.

The Time for Action is Now

The UK is looking for ways to manage the energy transition and for growth sectors of the future, and clean hydrogen ticks both boxes (and more). But global competition is ramping up quickly. The UK must learn lessons from past experiences in developing new energy technologies, as well as learning what is working elsewhere if it wants to establish a position as a global leader in hydrogen. Finally, the UK can’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Moving quickly to develop industrial clusters and focusing on areas of expertise will maximise the UK’s chances of success rather than trying to create all aspects of a brand new value chain at once.

Subscribe to our Climate Change and Sustainability E-Alert.

About Us

BCG's Centre for Growth brings together ideas, people and action to drive the UK forward. We work with our global expert network to identify transformational opportunities, connect key decision-makers and build coalitions for change. We offer long term strategic insight, extensive cross-sector expertise, platforms for dialogue and bias to action.